Reviews include Irena’s Vow, The Beast, and Before I Change My Mind.

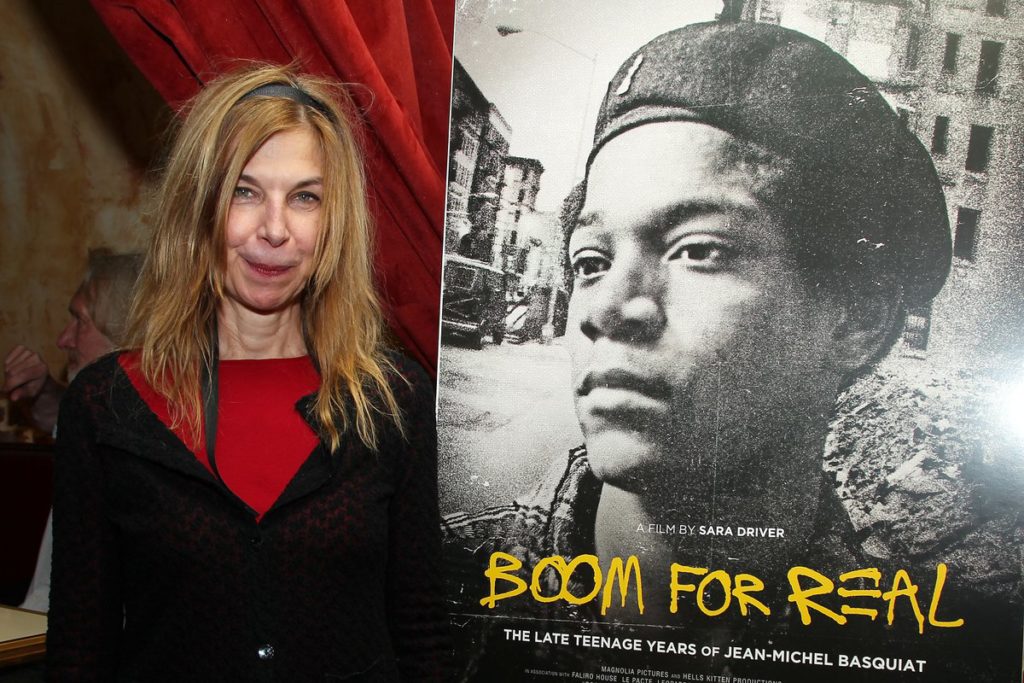

Boom For Real: Sara Driver on Basquiat, Collaboration, and NYC

May 17, 2018

“I want people to understand that Jean-Michel wasn’t some mythological figure. He was just this kid. He was finding his way.”

Sara Driver’s first directorial credit in over two decades is, on the face of it, her most conventional work. Boom For Real: The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat is largely comprised of archival materials and interviews conducted in homes or studios, but those archival materials are deployed and repurposed with playful invention, while the interviewees — among them writer Luc Sante, hip-hop pioneer Fab 5 Freddy, photographer and embryologist Alexis Adler, visual artist Al Diaz, and filmmaker Jim Jarmusch (Driver’s frequent collaborator and life partner) — are present as witnesses rather than, say, experts. They resemble a kind of adopted family in late middle age, scattered yet still closely linked, upholding the spirit of the period when they first met and experienced their inaugural creative surges.

The film’s full title is somewhat misleading. I would suggest that its broader theme is not the iconoclastic visual artist Jean-Michel Basquiat per se but, rather, the vibrant underground art scene fostered by the unique conditions of New York City in the late 1970s and early 1980s: the city was at an economic nadir and looked like a war zone; one could live for next to nothing and use that freedom to assemble, collaborate, and explore whatever medium drew one’s fancy. “Everybody knew everybody and everybody was doing everything,” declares one of Driver’s subjects, most of whom bear hyphenated job titles. Basquiat, who ascended to international acclaim before dying of a heroin overdose at age 27, is not profiled in any normative sense: we learn nothing of his family or upbringing, what transpired in his career after he catapulted into fame and fortune is only hinted at, and while his beatific image is all over Boom For Real, his voice is never heard. He’s a phantom presence, invoked by those who knew him as both an intimate and an enigma. Boom For Real is a documentary, but it possesses the sway and intrigue of fiction.

It is also something akin to memoir, albeit the sort of memoir in which the author largely removes herself from the story’s foreground. Driver was a part of the scene depicted in Boom For Real, which coincides with the earliest days in her remarkable career as producer, actress, writer, director, educator and, as Driver herself puts it, “instigator.” You can learn more about her work in this essay I wrote about her back in 2014, but for now let’s get to my conversation with Driver back in September, when Boom For Real had its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival. We talked about many things I couldn’t include here, like Roberto Bolaño’s evocations of youth, the Charlottesville riots and the way some Americans feel a new permission to be assholes in the Trump era, and how Joe Strummer couldn’t catch for shit. Driver was charming, engaged, and interested in everything, making it easy to imagine why so many artists over the years have worked with her or looked to her as a mentor.

Boom For Real opens in Toronto on Friday, May 18th.

José Teodoro: Part of what gives Boom For Real its special energy has to do with the way it captures a certain fleeting, galvanizing moment in youth. So I’d like to ask you about your own youth. When did you leave New Jersey?

Sara Driver: I skipped my senior year, so I was 16 when I went to college. It was 1973.

Did you know what career you wanted to pursue?

I thought I wanted to be an archeologist. I studied classics in college and lived in Greece. It was there that I got involved in theatre. I wrote a play that people kept saying was very cinematic and I didn’t know what that meant. Then I saw a Casavettes film that changed my life: A Woman Under the Influence. My dad worked in New York City and when they had meetings my mother used to drop me off at the cinema and I’d watch all the French New Wave films. I was quite young and would find myself wondering, for example, why this man was obsessed with Claire’s knee. Anyway I wrote this play and I applied to NYU graduate film school. That was in the Lower East Side and that’s where I met everybody and started making films.

Boom For Real champions the idea of an art practice as being determined by opportunity or sensibility. It’s anti-specialization, less to do with mastering a craft than ushering your sensibility into whatever medium you light upon. Which makes me curious how you spend your time. What do you do when you’re not making films?

I do master-classes at universities, things like that. I find it really stimulating to be around students. And I get involved with other people’s projects. I know a lot of people. I’m always teasing Jim [Jarmusch] that I’m working on my gravestone, trying to earn the title of “instigator.” I help instigate things that I’m not necessarily deeply involved with beyond the instigation point. I’ve written a lot of screenplays for films that I haven’t been able to get made. That takes an enormous amount of time, until you realize you can’t chase that carrot anymore and you’ve got to do something else. I also read and comment on a lot of other people’s screenplays. The reason this new film worked was because I just bought a camera and started shooting. I didn’t rely on anybody financially. Then a lovely Greek guy came along to give some support and I could at least put together a crew of four. It was just four of us making the whole film. A wonderful way to work.

Collaboration itself must be a major generator of creative energy for you.

Oh, absolutely. I remember Joe Strummer saying to me, “No input, no output.” I go to a lot of museums, to movies and theatre. One of my favourite things is to go to artist studios and see how their brains function. Collaboration is why I love film. It’s a medium grounded in the exchange of ideas. That’s why theatre’s so great too.

Your Basquiat, the film’s Basquiat, functions as a kind of ghost. We’re provided with no background and little foreshadowing. He’s someone who’s spoken about, always at this charismatic remove.

He was quiet. He was always watching. He was like a mushroom. He was always absorbing information and ideas. He loved ideas. That’s one of the things I wanted to convey in the film. Sam Fuller wrote a book called The Third Self. You never know a person’s third self. How do you ever really know a person? I knew Jean the way I show him in the film. This person we all knew from clubs. This person who was working non-stop. Very few people know he was a sculptor. Or that he painted on clothing. I think to know an artist is to know the ground that nurtured their art. This was a very specific time in New York, before AIDS, before big money came in. It wasn’t about money. It was about the transference of media and ideas. I felt that from the beginning of this process. I remember seeing Alexis Adler’s photographs of Jean and thinking this is a portrait of New York in time and it’s a portrait of Jean at his earliest experiments.

Part of the allure of the environment you’re depicting is that it’s so far from the mainstream, so disinterested in success, from penetrating the establishment. Something that separates Basquiat from virtually everyone else in the film is this clear-sighted ambition. He knew he was going to make it.

Right. The fact that he put all those tags up in an area full of people of influence in the art scene: he wanted the attention of the right people. On the poster for Boom for Real you see Jean-Michel wearing that beret. He was about 16, 17 when that picture as taken. I asked Al Diaz, “Was he trying to mimic Che Guevara? What’s with the beret?” Al said, “No, he just thought that was what an artist looks like.” [Laughs] I think Jean was extremely ambitious. That’s how he was built. We all have this drive or inner muse that takes us on a certain path. His was very strong. He was amazingly prolific. There’s very likely still work out there that hasn’t been found yet. He’s known to have done over 500, 600 canvases.

Trying to understand a particular place and time from the perspective of 35 years is a very different than after, say, five, ten, 20 years. My sense is that you’re revisiting this time in a way you wouldn’t have when you were younger.

It wouldn’t have interested me earlier in my life. You’re right about its perspective in time being essential to its motivations. Boom for Real was also motivated by the impulse to say to kids today, “Go ahead and try stuff. It’s okay to fail. Be in a band. Just try things.” I feel like kids today are afraid to fail. That’s a terrible pressure. I wanted the film to remind us of our freedom. Feel free to explore things. Go work with your friends. Because there’s a very competitive attitude now. And the pressure of money. What makes the period depicted in Boom For Real distinct is that we didn’t have the pressure of money. Back then you could live in New York for $75 a month.

But that’s the thing, right? New York in the early ’80s: I don’t know that there’s an equivalent to that today.

No, but there’s a feeling. We have a terrible world around us. We need our artists. We need our imagination gangsters to help us through this. If this film can help instigate something along those lines that would be an achievement. I feel like I made a good film, like what’s important here is human emotion and exchange and contact. I want people to understand that Jean-Michel wasn’t some mythological figure. He was just this kid. He was finding his way. All of us have talents that need fostering. Why not encourage that?

“We need our imagination gangsters to help us through this.”

Do you imagine yourself staying in the US, in New York specifically?

Those are two different questions. New York is really deep inside me. I was born in New York, though people say I was born in New Jersey. It was pretty rough there in the 1950s so my parents moved us out to Jersey, but I was always going into the city since I was little, always with this determination, with this idea: “I’m gonna live in New York City someday!” The city has changed, but I still get a lot of input. I need those museums. I need those 40-year friendships with people who are still there. I wish we would secede, like Luxembourg or something, and not be part of this country anymore, which now seems alien to me in many ways. I don’t know where else we could go. Jim and I have a small place in the country and I love that too. Both those worlds are very nurturing.

There seems to be a hunger in Jim’s films for travel. He’s thought of as a New York filmmaker, but really, almost all his films explore places far from New York. I mention this because I imagine that by building these projects together that take you guys abroad might feed the desire for elsewhere.

Yeah, that’s true. Making art can facilitate that need, give you a dose of what you’re missing. I’m just thinking, though, with regards to your previous question, that I’ve been living downtown a long time. I wouldn’t mind leaving. All these rich kids. I used to feel very safe downtown with the bums, everyone taking care of each other. Now, with all these drunk rich people around I feel uneasy. I’d like to move uptown, and that’s a whole other New York. They still have sky there. They haven’t covered Harlem with skyscrapers.

After delving back into this period of time that was so rich in discovery and creativity, do you feel like there are new paths opening up for you?

Very much so. I’ve noticed that there are few live-action films for children. It’s all Pixar, which are often really good but aren’t creating an audience for cinema. They’re closer to video games. I’ve been collecting metamorphosis stories, human-to-animal, animal-to-human stories, from around the world, so that kids have an understanding of global storytelling, of how to understand other cultures in a fun way. I want to do the whole project using light and shadow, in-camera effects, shooting on film. I want to make it magical, but without the use of fake, computerized effects, because they feel different than if you do them in-camera. Light and shadow is simple and powerful. You can make something spooky just by dimly lighting it. That’s a project that’s very dear to my heart.

Which takes you back to your classics studies.

Yes! I remember teaching at NYU and none of my students knew basic mythology, which is the basis of most literature. Those archetypes are so important. I felt like the students were on boats without any sort of anchor, you know? We’re so separated and we don’t understand other cultures. Especially in America, where we’re not welcoming to other cultures anymore, which is so sad because that’s how we became such a rich country, through diversity. I think it would just be great if kids saw a story from Saudi Arabia and then understood something about that culture.

Do you have other projects you feel ready to move on?

I’d like to do a series of little essay films about the people in Boom For Real. Like Lee Quinones. He painted almost a thousand trains. He started when he was 13. He told me that he used paint inside his mother’s kitchen cabinets before he would go out to the train yards. He’s really important. And Fab 5 Freddy is such a vital voice. This is something I could do with my newly bought camera!

It would be interesting to make one of those little essay films about someone who didn’t wind up pursuing a career in the arts.

Well, look at Alexis! She’s an embryologist. She started the fertility program at NYU. She was studying tropical diseases at Rockefeller University when Jean was living with her. Then Regan dropped all the funding for tropical diseases, so she made her way into this new thing called the fertility business. She’s now one of the most acclaimed embryologists in the world. People don’t even know that she’s a serious scientist who’s invented ways of changing DNA within the embryos. I shot all that stuff of her in the lab. I have that material ready; I can just edit it. I take great inspiration from friends like her, people whose sense of artistry, whose vision, roams to places that aren’t necessarily about making art. All that really matters is being resourceful and living creatively.