Reviews include Civil War, In Flames, and The Greatest Hits.

Festival Diary: The 46th Festival du nouveau cinéma

October 19, 2017

One of the most rapturous experiences at the movies this year.

A single flashlight wends along a sandy beach.

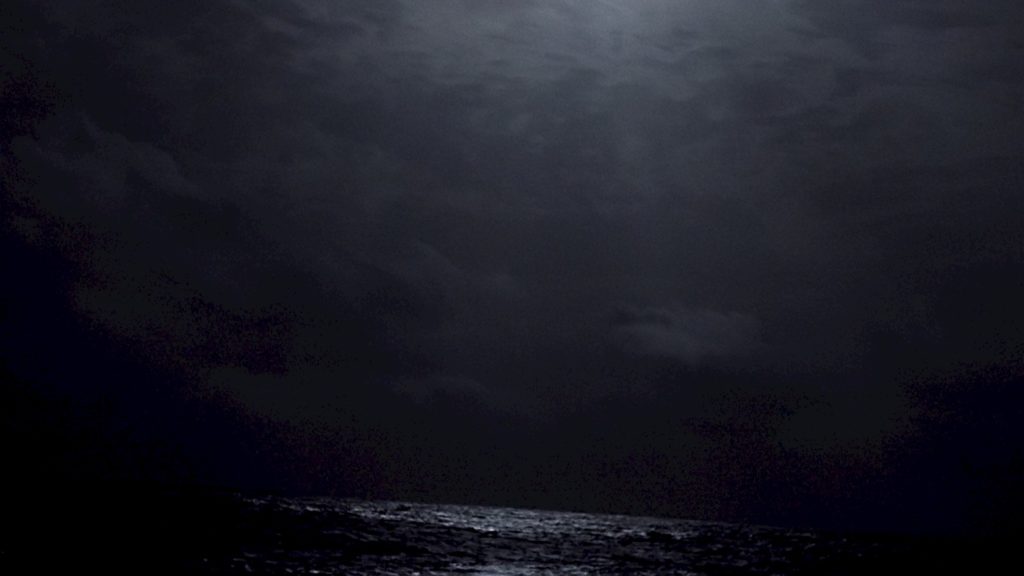

A moon falls into cranes. Shadows ripple across a sail. Hard shards of sunlight roam across a sleeping face, appearing and vanishing like sprites. Transfixing images accumulate as we get gently dragged deeper into Drift—and that’s before the film’s turning point, when the soundscape slowly slips from the diegetic into electronic abstraction and the sea wrests control of the helm and we really start to lose our sense of time and space. Water like velvet, like elephant flesh, like parchment, like long dark hair: I’ve never seen a narrative film so attuned to the movement, thrall and diversity of the sea as German director Helena Wittmann’s feature debut. Though, to be fair, Drift is only barely a narrative film.

From the official synopsis: “Two women spend a weekend together at the North Sea. […] One of them will soon return to her family in Argentina, whereas the other one will try to come a step closer to the ocean. She travels to the Caribbean […] The sea takes over the narration.” The latter woman eventually returns to civilization and Wittmann finds echoes of the sea in the wash of a revolving door or in waves of things passing outside a train window. The woman finally finds herself in a comfortable domestic space where R&B plays on the computer and wildness, like most everything else, is contained within the confines of a frame. Drift takes us far, far out and brings us back home. It’s easily one of the most rapturous experiences I’ve had at the movies this year. You might figure it for something in the Wavelengths program at TIFF, but no, I saw it in Montreal, at the Festival du nouveau cinéma.

The politics of Montreal film festivals, fraught with feuds and allegiances, along with questions of relevance and regional representation, can be difficult to parse. All I know is that when I attended the Festival des films du monde five years ago and balked at the low quality of its films, my Montreal colleagues kept telling me I was at the wrong festival. Founded in 1971 by Claude Chamberlan and current TIFF programmer Dimitri Eipides, the Festival du nouveau cinéma has undergone many changes in name, mandate, and scale over the years, but seems to have maintained a more elevated standard of film programming. I was finally able to attend FNC, which wrapped its 46th edition on Sunday, and caught some marvelous films that I might not have otherwise, as well as some memorable special events, such as a screening of the 1915 German horror classic The Golem, featuring a rangy live musical accompaniment composed, conducted and co-performed by Josh “Socalled” Dolgin, who drew from everything from avant-jazz, Syrinx and post-rock to trip-hop and Michael Jackson to underscore this eerily anti-Semitic fable about anti-Semitism. I also got to finally see Saul Bass’ amazing 1974 science fiction chamber film Phase IV and will never feel friendly toward ants again.

The prolific Mike Hoolboom’s Incident Reports premiered at the Images Festival last year, but I only caught up with it at FNC. Which in a way was probably preferable since watching this Toronto travelogue with a Toronto audience might have felt a little too cozy—and Incident Reports is designed to be anything but. An essay film in the guise of fiction, Incident Reports is composed of a series of one-minute shots taken by an amnesiac accident survivor struggling to recover memories and corporeal health via an audiovisual mediation therapy program. Musings on animals, history, gender, capitalism and the erosion of the private and the literary from our culture nestle against images of aquariums, roller derbies and naked bicycle convoys. Peripatetic in body and thought, the film is deeply charming and steadily sets off chains of pertinent, percolating ideas. I don’t think the conspicuous discrepancies between what’s seen and heard work especially well, but this is nevertheless an elegant, smart, playful work of lo-fi cine-exploration.

Meteorlar won something called the Swatch Peace Hotel Award at Locarno this year, but it only made its first appearance over this continent at FNC. Turkish director Gürcan Keltek’s second feature documentary is a problematic yet extraordinary meditation on violent events celestial and terrestrial, fleeting and seemingly endless. Delivered in monochromatic images that render shadows a deep black and various luminous phenomena a stark white, Meteorlar (Turkish for Meteors; I haven’t found a consensus yet on the English title) essays on the death and destruction wrought upon Kurdish villages in Turkey, moving between scenes of hunting, festivities, civil unrest, stargazing and Kurdish children playing in rubble or describing what can only be categorized as a humanitarian crisis.

The testimonies are harrowing and the evidence of indiscriminate violence on the part of the Turkish authorities is exhibited in abundance. The film’s demand for closer attention to the situation is clear, sometimes too clear: actress and writer Ebru Ojen Sahin’s voice-over narration works fine with regards to providing meaningful, personalized context, but her appearances onscreen, her handsome face expressing concern or moodily sucking on cigarettes, is superfluous and mawkish. Far more compelling are the film’s unspoken connections between deadly explosions, celebratory fireworks and meteor showers, which we behold galloping toward Earth like some apocalyptic cavalry. To mark surviving falling bombs by lighting up the sky with fire and smoke: it is a moving act of defiance and makes for one of the more indelible sequences in any nonfiction film this year. I’m grateful to FNC for giving this film a screen in Canada, and hoping other programming bodies follow suit.