Reviews include Irena’s Vow, The Beast, and Before I Change My Mind.

#PutDownThePhone, Take Down The Ad: Systemic Ableism in the Ontario Ministry of Transportation’s Button-Pressing PSA

August 17, 2016

by Angelo Muredda

Between Me Before You and the mass killings of Sagamihara, it’s been a banner summer for systemic ableism.

And what better way to drive home the message than a public service announcement? The genre has had a memorable tradition in Canada, well-covered in Robyn Caplan’s 2010 Gawker article “PS-eh? The Craziest Canadian Public Service Announcements,” which serves either as a time capsule for adults of a certain age or a strange otherworldly primer, depending on which side of the 49th parallel you fall on.

More hectoring than a Grimm fairy tale compendium, Canada’s after-school PSAs have tended to warn children of the myriad dangers that come with having a fragile body. Consider the War Amps’ series starring Astar the Robot from the Planet Danger, who navigates a world of live wires and arm-severing razors, and suffers an amputation, the better to warn kids that while he can put his arm back on, they can’t.

Whatever their good intentions, ads like Astar’s and the deservedly-memed “Don’t Put It In Your Mouth,” where a cadre of blue puppets sing a warning song about imbibing mystery substances not approved by “someone you love,” have long insisted that Canada’s youth treat their bodies as an ever-besieged temple, one step away from catastrophe.

As dark portents go, though, nothing tops the new distracted-driving ad cooked up by Ontario’s Ministry of Transportation, and broadcast before countless Cineplex escapes and YouTube videos in 15, 30, and 60-second versions. Simply called “#PutDownThePhone,” the most circulated 30-second version sees a handsome, floppy-haired young man gliding his car through traffic to the tune of generic new wave muzak. He glances at his beeping phone, then picks it up to respond. As he rolls through an intersection, a truck slams into the driver’s side door. Just as his head bounces off the airbag, the teen is reframed from side profile to a brief frontal tableau, his violent jerk back to the carseat rhymed in a smash cut that relocates him to the headrest of a wheelchair. Once affiliated with the easy mobility of his car, the teen is now perfectly static; staring just off-side to the camera with flat affect, his supporting medical apparatuses and hospital bed out of focus behind him, a tracheotomy tube fastened around his neck. “It happens fast,” an onscreen caption reads, and when we return to the teen he’s now abandoned in the centre of the frame in a tilted wheelchair, the hospital room motionless save for the slight flutter of the window blinds beside him, just out of reach.

As in “Don’t Put It In Your Mouth,” few would disagree with the ad’s basic premise: don’t be an asshole who texts and drives. One wonders, though, how much of its rhetorical effectiveness comes from its shameless exploitation of a knee-jerk ableism that can’t envision living with a disability as anything other than the violent conclusion to a life of self-determination. If the ad is a success, it is because it painstakingly cultivates a visceral reaction to the sight of our once-dynamic surrogate character dramatically restrained. The real money shot in the ad isn’t the sight of the incoming truck, or even the grotesque image of the teen’s head bouncing off the airbag. No, it’s the figurative connotation that as a result, his horizon has been abruptly narrowed from the roaming space of the car to the confined hospital room, and from a vehicle that has long signalled freedom and youth in the North American popular imagination, to another that has signalled degeneration and old age.

There’s nothing inherently degenerative, though, about wheelchairs, a hallmark of assistive technology that enhances rather than restricts mobility and autonomy for most who use them. (It’s probably an unfortunate testament to the ad’s button-pushing success that even the usually tasteful CBC refers to the teen as being “confined to a wheelchair” in an article about the campaign’s ubiquity.

His horizon has been abruptly narrowed from the roaming space of the car to the confined hospital room, and from a vehicle that has long signalled freedom and youth in the North American popular imagination, to another that has signalled degeneration and old age.

In this regard, the spot has deep roots: not just in Canadian PSAs about the terrible things that can happen to your body, but in cinematic depictions of disability — and, more specifically, the use of a wheelchair — as a corruption of humanity’s natural upright, bipedal state, and a form of imprisonment that holds the self captive in its own body. These tend to have a generic quality to them that only slightly exaggerates the primal fear behind the depiction.

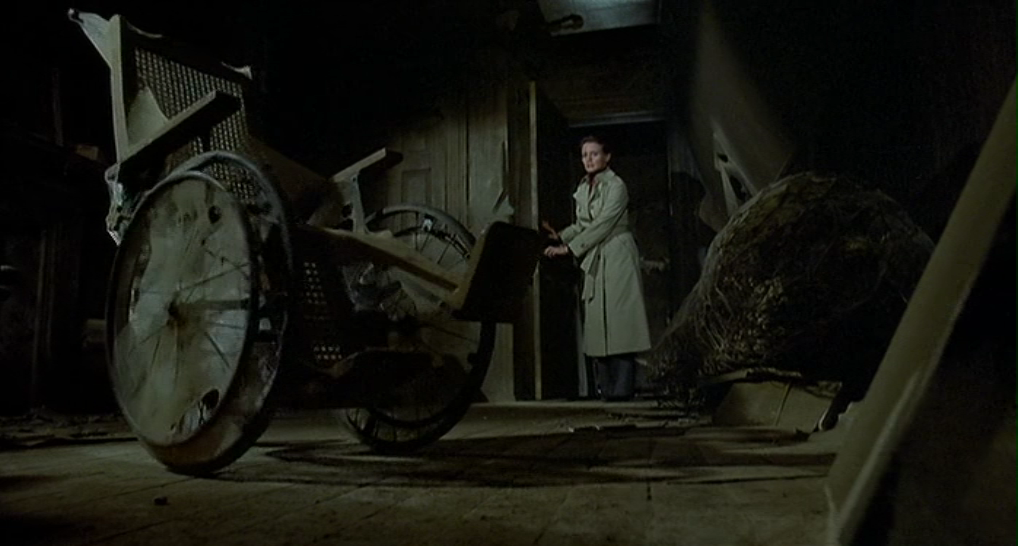

If Astar comes from science fiction, the Ministry’s PSA owes a debt to fantasy and horror. The teen’s forcible confinement to his new chair might remind Canadian genre fans of the abandoned rickety wheelchair haunted by Joseph the unloved disabled child in Peter Medak’s The Changeling, banished to the attic before he is drowned in a bathtub. This treatment of the wheelchair as a place of containment also echoes John Carpenter’s use of it as a mode of prisoner transport in Big Trouble in Little China, as well as David Robert Mitchell’s more recent Carpenter-riffing thriller It Follows. Absent in all of these examples — including the PSA — is the slightest expression of agency on the part of an actual wheelchair user, as though the spell would be broken if we saw a disabled character as a subject, using a wheelchair in a non-symbolic way.

The ad has more mundane antecedents in human interest dramas that similarly frame disability as a terminal point to a fulfilling life. Earlier this summer, disability activists made waves in their protest of Thea Sharrock’s Me Before You, a more or less faithful adaptation of Jojo Moyes’s bestselling novel about Will (Sam Claflin), an impossibly rich, impossibly good-looking bon vivant whose life of able-bodied privilege and indulgence is ended when a motorcycle accident paralyzes him from the neck down. Though much of the film riffs on its Beauty and the Beast plot of a grumpy malcontent pulled to the light by a bubbly soul Louisa (Emilia Clarke), the film’s last act pivots into an astonishingly clunky essay on the discounted value of disabled lives. Will interrupts the nascent couple’s latest seaside vacation to explain his plan for a quiet assisted suicide in Switzerland, reasoning that if he can no longer be the active man he used to be, then he has no more use for life — even if that life happens to unfold in castles and private jets. The film occasionally makes vague gestures to Will’s pain and infrequent bouts with pneumonia to justify its appropriation of right-to-die discourse for its better-off-dead messaging. But it is the tidy signifier of his wheelchair, which ostensibly creates a physical barrier between him and Louisa, that turns all of his riches and all of his love to dust.

Me Before You’s hard swerve to proselytizing about the compromised value of a disabled life makes it a particularly egregious example of this ableist rhetoric, but it is merely taking its cues from more pedigreed films like Clint Eastwood’s Oscar-sanctioned Million Dollar Baby. Though it is less outwardly schlocky, the film is arguably more transparent in its distaste for the aesthetics and paraphernalia of disability. Where Sharrock has the courtesy to light up Will’s wheelchair in the same sunny hues as the rest of the film, Eastwood’s lighting, desaturated even on a good day, casts his central character Maggie (Hilary Swank) in an even more sickly pallor than his other characters after a boxing injury ends her career and relegates her to a wheelchair for mobility. The already fair-skinned Swank becomes a radioactive shade of green post-injury, her body framed in increasingly unflattering compositions: either parked in her chair with her back to the window, not unlike the teen in the ad, or supine and incubated in the hospital bed where Eastwood’s coach eventually administers the fatal shot that she, like Will, demands.

It might be tempting to dismiss these aesthetic and thematic similarities as coincidence, or as earnest attempts either to grapple with the all-too-human fear of what comes next or to warn about the consequences of embodied living, short of total vigilance. If we take images seriously, though, it is our duty to acknowledge that they make things happen. It ought to be more difficult, for instance, to divorce the Ministry’s depiction of disability as an undead state of complete dependency from the rhetoric of the man behind the Sagamihara mass killing of 19 disabled people in Japan, who wrote letters to the House of Representatives espousing his goal of “a world in which the severely disabled can be euthanized, with their guardians’ consent, if they are unable to live at home and be active in society.” That isn’t to say that there is a direct causal link between dehumanizing rhetoric and violent actions. Together, though, these grotesque images and anxious cautionary tales create a dangerously homogenous visual language of disability as a zombified existence from which previously healthy people cannot return — muting if not altogether erasing the incredibly varied embodied identity it is for the people who actually use those haunted wheelchairs.