Reviews include Irena’s Vow, The Beast, and Before I Change My Mind.

TIFF: Forwards, Backwards, and Every Which Way

August 14, 2014

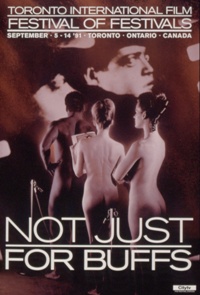

The first time I went to Toronto International Film Festival, it wasn’t even called the Toronto International Film Festival. It was the Festival of Festivals, held along Bloor Street in a handful of Toronto theatres–the Uptown, the Cumberland, the Varsity, the Bloor.

For the most part, the press saw the movies along with the public; the festival held just a handful of press screenings every day, usually in the rickety old Backstage, tucked around the corner from the Uptown. If you wanted to see something that wasn’t being screened for the press, you lined up with everybody else for half an hour or more, chatting with civilians, hearing about this new filmmaker or that emerging title.

I remember wandering out of the Manulife Centre after an afternoon Varsity screening in 1991–the year of Barton Fink–and literally walking into Steve Buscemi, who was blinking in the sunlight like a mole person. Buscemi would be back next year as part of the Reservoir Dogs gang, and we’d have a proper interview; that was back in the days where you’d get a half-hour’s sit-down with one person, simply because there weren’t dozens of other journalists clamouring for time.

NB: This will not turn into a those-were-the-days piece. But I do want to focus on 1992 for a moment, because it’s my single favourite TIFF and it does represent an experience of the festival I haven’t had since.

In terms of TIFF, 1992 was the year of scrappy, idiosyncratic mission statements like Reservoir Dogs and Bad Lieutenant and The Crying Game and Strictly Ballroom and Hard-Boiled and Jean-Claude Lauzon’s brilliant Léolo.

This was the festival with the single greatest Midnight Madness lineup in the festival’s history, featuring Man Bites Dog, Tokyo Decadence, Candyman, Romper Stomper, Tetsuo II: Body Hammer and Peter Jackson’s Braindead, which would ultimately be retitled Dead-Alive and still be just as much bloody fun.

It wasn’t all perfect. Gary Sinise’s Of Mice and Men and Kenneth Branagh’s Peter’s Friends failed to set their respective theatres on fire, and Howard Franklin’s The Public Eye and Darrell James Roodt’s Sarafina! enjoyed that curious film-festival distinction of being heavily buzzed properties right up until their first screenings, after which the conversation immediately turned to other things.

But this was a point in TIFF’s evolution when the festival was small enough that none of its selections felt overshadowed by the others; you didn’t have to gamble on picking the right movie out of four potentially great choices. (And if you found yourself stuck in a dud, you warned people away from its second screening–and they directed you towards the repeat of something they’d really liked.)

It was busy–insanely busy–but it didn’t feel cluttered. And because TIFF hadn’t yet become TIFF, smothered by the crush of international media, American publicists and tens of thousands of people who just want a selfie with Benedict Cumberbatch, you could pop into the whirlwind and come out the other side having seen more or less everything you wanted to see.

People who’ve been coming to the festival since those days–or even further back, since its beginnings in the 1980s as a showcase of world cinema–are the first to complain that things were better back in the day. I would say they have a point; the civilian, general-audience experience of TIFF has radically changed over the decades.

Tickets are much more expensive, with galas and certain special events priced well beyond the range of casual interest. Sure, you can go see that special Conversation with Al Pacino, or you could buy the Godfather trilogy and Heat on Blu-ray and still have money left over for a nice dinner.

The lines are just as long, if not longer, and now you get the added joy of sharing your space with screeching fashionistas and autograph hounds who have no intention of seeing the movie; they just want to watch the red carpet and get Meryl Streep to acknowledge their existence.

The movies? Well, they’re not secondary to the experience. Not yet. But they’re starting to tilt that way thanks to two key factors.

First, there’s TIFF’s status as a launching pad for Oscar hopefuls, a snowball that started rolling in the early ’90s, and only got bigger and more intimidating when virtually every major Academy Award for 1999 went to a movie that had played here. (American Beauty took Best Picture, Actor, Original Screenplay and Director; Boys Don’t Cry, Best Actress; The Cider House Rules, Best Supporting Actor and Best Original Screenplay. Girl, Interrupted took Best Supporting Actress; I think it premiered at New York.)

If you’re a producer or distributor with an eye on an Oscar run, you come to TIFF. And TIFF will be happy to have you: the festival and the Academy feed off one another very nicely. The festival has also managed to convince Hollywood–or at least Harvey Weinstein–that the People’s Choice Award is a gateway to a Best Picture win, even though it’s happened only five times in the festival’s history. Chariots of Fire did it in 1981, American Beauty in 1999, Slumdog Millionaire in 2008, The King’s Speech in 2010, 12 Years a Slave in 2013. (Sure, three of those were in the last six years, but it’s stretching it to call that a trend.)

And then there’s TIFF’s problem with celebrity. Although I suppose the festival doesn’t have a problem with celebrity at all; it’s resoundingly for it, scheduling generic junk like Renny Harlin’s Cleaner and David J. Burke’s Edison (retitled Edison Force for DVD, a title which somehow seems even less distinctive despite the extra syllables) for splashy red carpets because they featured friends of the fest like Samuel L. Jackson, Ed Harris, Morgan Freeman and Kevin Spacey. Yes, we launch movies that might otherwise go straight to video … but we also launch a lot of movies that ought to go straight to video.

And yet, if you push yourself beyond the screenings that come with their own step-and-repeats, TIFF still merits its place in the international circuit. They bring greatness; they book giants. Generations of Canadian filmmakers have been anointed here; European and Asian cinema continues to be welcomed. African film hardly screens in Toronto, but at TIFF, the directors and stars are embraced by crowds of a scale simply not seen at any other point on the calendar.

And the Midnight Madness screenings are still the most fun you can have in a Toronto theatre, though I have yet to recapture the electricity of that Braindead screening in 1992, when Quentin Tarantino clapped me on the shoulder on the way out of the Bloor at 2 AM, most of his exhausted Reservoir Dogs cast trailing behind him. I think it was Steve Buscemi, Michael Madsen, Chris Penn and Lawrence Bender, their bleary faces bobbing up and down behind him as the crowd flooded out of the theatre into the street.

“That was fucking amazing, wasn’t it?” Tarantino shouted, and I agreed that it was. Peter Jackson was a few feet away, shaking hands and talking to overjoyed fans about how much blood he used for the big lawnmower scene. We went over to say hi. Rather, Tarantino did, pulling the rest of us along in his wake.

Hardly anyone else knew who Tarantino was, if you can imagine such a thing: just some weird-looking fan who was as high on the movie as everyone else. There were no cell phones around, of course, but neither were there paparazzi nor official Festival photographers hanging around to capture the moment; no one paid any attention to Midnight Madness, it was where the geeks hung out. Geeks who’d change the course of filmmaking and become household names–but not just yet.

Now, such a meeting would be stage-managed and conducted in front of a crowd, the talent shouting to be heard over the cheers. Even the Midnight Madness screenings have red carpets now, if a movie as star-studded as Seven Psychopaths is playing.

It’s a different world.

Different, but maybe better. The omnipresence of social media and the constant turnover of entertainment news all but guarantee a worthy picture will find its audience. Hell, conventional media does a decent job too; I managed to push Manakamana, A Touch of Sin and A Field in England to CBC Radio listeners last year, and my gig at NOW Magazine certainly allows me to highlight titles that don’t have studios or superstars behind them.

We can’t go back to the simplicity of the past. And to be fair, the overstuffedness of TIFF is a cinephile’s dream: if one screening is sold out, there is always something else a few steps away. Short films and features look gorgeous in the comfortable screening rooms of the glorious Lightbox, and digital projection failures are thankfully rare enough that everyone hears about them long after they’ve been remedied.

And for all the SUVs and security coordinators and clipboard wielders who make you cross the street twice to get to a door that’s three feet away, TIFF is still a street-level festival. You can still experience the jolt of bumping into Sandra Bullock on your way to see her new picture. And if that picture turns out to be a truly revolutionary work like Gravity, well, so much the better.

Norman Wilner is the senior film writer for NOW Magazine. He has been the vice-president of the Toronto Film Critics Association since 2008.