Reviews include The Last Showgirl, Soundtrack to a Coup d’État, and Wolf Man.

Good Men, Good Women: The Films of Hou Hsiao-hsien

January 29, 2015

On now at TIFF Cinematheque: the films of Hou Hsiao-hsien. Adam Nayman revisits the formal rigor and verisimilitude of Hou’s work:

One evening, at the 2006 Rotterdam International Film Festival, I was invited by a colleague to sit at the end of a long dining table in the festival complex where the renowned Taiwanese film director Hou Hsiao-hsien was holding court. Small-shouldered and sporting a baseball cap, he was hardly an imposing figure, but I wasn’t about to approach him. I’m rarely at a loss for words around filmmakers – it’s hard to conduct interviews when you’re tongue-tied – and yet at the time I didn’t think that I would have been able to do much except gush about his work, which would have probably been boring for everybody. So I settled for looking down the table to see if the guest of honor was enjoying himself. The impromptu sculpture garden of discarded beer bottles partially obscuring my view suggested that the answer was yes.

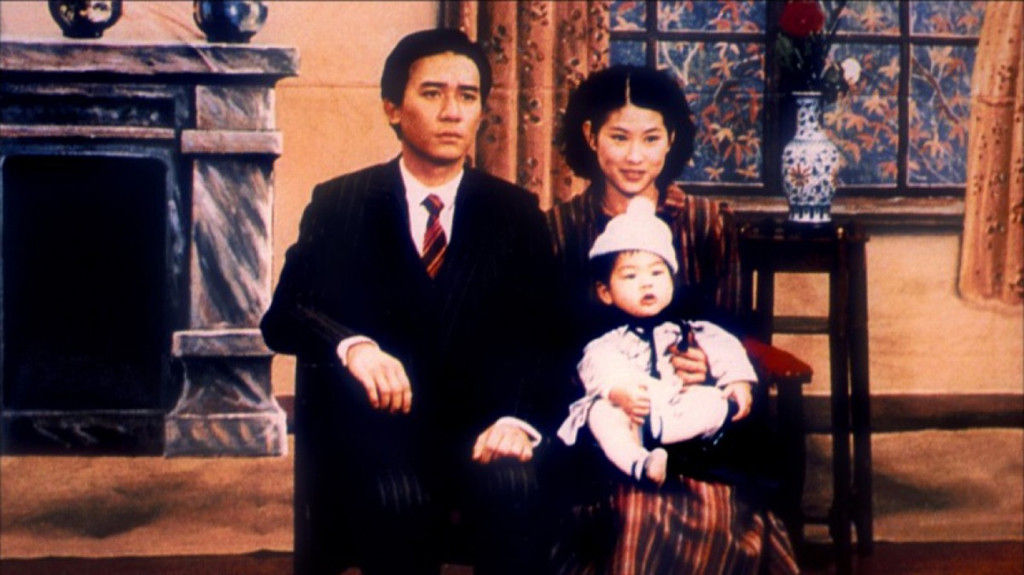

It’s an incredibly vivid recollection of what was basically a non-event, and it’s stuck with me over the years as I’ve continued to watch (and re-watch) Hou’s films. Few directors have ever been as adept at inscribing the feeling of the long-view. As James Quandt notes in his essay for TIFF Bell Lightbox’s upcoming retrospective, Hou’s interests have shifted over the years from the present tense to the past and back again (with his low-budget 1980s output now transformed into period pieces by the passage of time) and he’s made two genuine national epics: City of Sadness (1989), about Taiwan’s difficult transition after World War II from Japanese occupation to an equally repressive nationalist regime, and The Puppetmaster, which spans the first half of the 20th Century (essentially ending where A City of Sadness begins).

These two masterpieces, which each encompass a wide swath of social, political and cultural history yet remains consistently intimate in its visuals and storytelling, are perhaps maybe the greatest of the many remarkable features on display during TIFF’s series, which has been mounted in collaboration with Bard College and the Taipei Film Institute in New York and the Taiwan Film Institute and the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of China. The transnational flavor of this arrangement hints at Hou’s status as an artistic hero both at home and abroad, although as is so often the case, his reputation was made in the West first. It has been said that his early films – along with those of his countryman and friend Edward Yang – permitted Taiwanese cinema unprecedented exposure in North America (the late, famed Toronto International Film Festival programmer David Overbey was one of the director’s major champions in the 1980s).

What critics may have been responding to in the beginning was a formal rigor reminiscent of a previous Asian auteur – Yasujiro Ozu – but as Quandt points out, Hou hadn’t actually seen any of the Japanese master’s works. This is probably not surprising considering the years of Hou’s upbringing (the complex and difficult relationship between Taiwan’s citizens and Japanese culture is quite beautifully elucidated in City of Sadness), but it also begs the question of what Hou’s influences actually were. In an essay in the Austrian Filmmuseum’s new critical anthology Hou Hsiao-hsien, Kent Jones suggests that one superficially unlikely candidate is Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather (1972), a film that he locates as the primal scene of “environmentally grounded cinema,” in which the documentary reality of a particular setting – like the massive Coreleone family wedding that serves as a kind of overture –imbue the fiction with a sense of authenticity. Jones connects this sense of authenticity to memory – the total recall of spaces and places: Hou’s films are suffused with a nostalgia that at once mediates and heightens their verisimilitude. The editing progression in The Puppetmaster (1993) that condenses a series of major events in the life of the protagonist into a quick series of shots belies Hou’s reputation for “slow cinema,” and yet the speed of the sequence is also in keeping with his insistence on realism. Time keeps on slipping into the future.

With this in mind, it’s been exactly eight years (to the week if not the day) that I declined to approach Hou Hsiao-hsien, and it’s a memory that’s grown increasingly regretful — and wistful – in retrospect. Whether this sensation is a validation of the director’s aesthetic or a byproduct of consuming so many of his movies is hard to say, but either way, I’ll always remember it in every way as my “Hou moment.”