Reviews include Irena’s Vow, The Beast, and Before I Change My Mind.

In Good Time and Bad: Wim Wenders

February 1, 2016

Where do we start with Wim Wenders? “At the beginning” is the obvious answer, especially since the earlier films tend to be far stronger than the later ones.

But that’s just it: few filmmakers bear a trajectory so fraught with such chasms of variability, despite—or because of—their propensity to work within the range of established strengths, sensibility and thematic.

There may be better analogues in music, the art-form one imagines Wenders cherishing above all others. Does Stevie Wonder fit the bill? 11 years divide the exquisitely textured masterpiece of Innervisions from the sonically gaunt drivel of ‘I Just Called to Say I Love You.’ 13 years divide Paris, Texas from The End of Violence, and I am not bashful about declaring Paris, Texas a masterpiece. When charged with devising a top ten of all time for Sight & Sound in 2012, I wound up selecting Paris, Texas over works by the filmmakers I revere most. A kick in the pants to auteurist purity, except that Paris, Texas, like most of Wenders’ work, is a categorically auteurist film, drawing from the talents of many to serve the vision of one. But I’m a romantic. If I love deeply Paris, Texas, which I am not bashful about declaring a masterpiece—or Alice in the Cities, or The American Friend, or Wings of Desire—I feel I should somehow love deeply its author. But it’s hard to love deeply the guy who made The Million Dollar Hotel.

“The camera is a weapon against the tragedy of things, against their disappearing,” Wenders wrote in 1987 in a micro-essay entitled ‘Why Do You Make Films?’ This raison de créer aligns Wenders with fellow German W.G. Sebald, a writer, not a photographer or filmmaker, though a writer fond of inserting images, captionless and enigmatic, into his texts. The notion of filming against the dying of the light suits Wenders, not only because of the crepuscular allure of so many of his finest sequences, but because many Wenders’ films are about the ache and beauty of fleetingness and passage, the passage of time and space. Wenders has an angel sacrifice his immortality just to feel such passage. It is surely no coincidence that, according to that same 1987 essay, the first thing Wenders ever shot, at age 12, with an 8mm camera, was a street, viewed from above, anticipating a life spent making road movies (as well as an inordinate number of aerial shots).

I am not bashful about declaring Paris, Texas a masterpiece

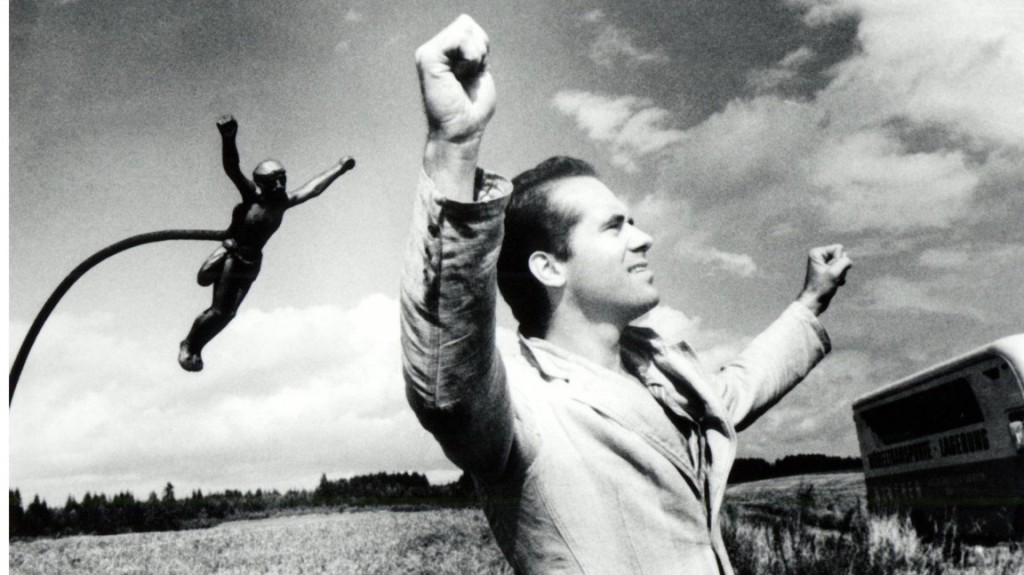

Young Wenders had a knack for turning material that didn’t necessarily feel like a road movie into a road movie. The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick (1972) shouldn’t have even been a movie at all, given that Peter Handke’s eponymous, masterfully controlled source novel is so intrinsically about language, ultimately using the breakdown of language to mirror a psychic breakdown. Yet Wenders, in collaboration with Handke—and, crucially, cinematographer Robby Müller—created something if not precisely equivalent to the novel then certainly complimentary by using the tools of cinema, shifting between ellipses and continuity to invoke its sociopathic protagonist’s increasingly compartmentalized mind. There is no attempt at interiority. We know the protagonist is a goalie, we know women like him and he likes jukeboxes, we know he’s reconsidering his breakfast routine, but we can never be sure why he decided to kill that cinema cashier or anyone else. Did he even decide, or was it what Jimmy Stewart in Anatomy of a Murder calls an “irresistible impulse?” Was it the fault of the movies, and the woman’s role as gatekeeper to fantasy? The film’s psychology seems to have everything to do with movement and vision—can you watch a soccer match and just keep your eyes on the goalie? Wenders made Goalie’s Anxiety into a traveler’s tale. Even when the camera is on the protagonist we’re generally looking out, not in, logging things as they pass. Wenders and Müller seem incapable of photographing any location in a straightforward or boring way, whether a hotel lobby, soccer field, gas station, country kitchen, bowling alley, or an elevator ascending the side of a building.

“Who loses their way these days?” asks a character in Goalie’s Anxiety. The answer: every significant character in Wenders’ entire filmography. Following the somewhat anomalous Hawthorne adaptation Scarlett Letter (1973), Wenders made the trilogy that brought his sensibility to its full fruition, every one of them possessed by wanderlust, with destinations and itineraries perpetually taking a backseat to the spirit of journeying for its own sake. In Alice in the Cities (1974) a German photojournalist (Rüdiger Vogler) in New York is entrusted with the young daughter of a woman’s he’s just met. He escorts his charge back to Europe, loses touch with the mother, and with the girl as his unreliable navigator traverses a considerable swath of Germany in search off the girl’s grandmother’s house. Far-fetched as the premise may be, the photojournalist and the child develop one of the most convincing and endearing inter-gender relationships in Wenders’ filmography. The Wrong Move (1975) reunited Wenders with Handke, who adapted Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship, which Wenders also renders as a road movie, albeit a geographically contained one in which a young, naïve, romantic German (again, Vogler) leaves home to become a writer. Chance encounters are key here as well, most notably with that first arresting apparition of Hanna Schygulla at, naturally enough, a train station.

Many of his films are about the ache and beauty of fleetingness and passage, the passage of time and space

Kings of the Road (1976)—the English title is dopey, the original being Im Lauf der Zeit, or “All in Good Time”—completes Wenders’ breakthrough and marks the first time that he starts pushing duration aggressively to suit his aims. A pediatrician (Hanns Zischler) reeling from a recent separation makes a flamboyantly fumbling suicide attempt right in front of a traveling film projector repairman (again, Vogler—this guy will travel with anybody). With his Beetle drowning in a lake, the pediatrician climbs into the repairman’s massive truck, where he’s given coffee, dry clothes, is asked no prying questions, and gets to sit back and listen to a car stereo that plays 45s (an item I’ve hopelessly coveted ever since seeing this film). The repairman offers the pediatrician the consolation of silent companionship. Based on their few exchanges it’s hard to know if these two are protecting or trying to exorcise their loneliness. They travel. “Nothing happens.” Or, rather, everything happens, in good time. Kings of the Road is indeed a weapon against things disappearing: cinemas, for one, but, more importantly, women. We are from scene one in a world of men without women, a kind of melancholy western—Ride the Low Country?—that shakes off plot in favour of the accretion of feeling and taking measure of the state of things in 1970s Western Europe. At 175 minutes Kings of the Road is just long enough to allow us to feel for a while as though we have been traveling long along with the characters.

Male friendship is just as central to The American Friend (1977), which also functions wonderfully as a thriller and a mediation on national identity in the postwar era, despite the fact that Wenders seems to have understood perhaps half of what was happening in Ripley’s Game, Patricia Highsmith’s ingenious, profoundly sinister crime novel upon which the film is based. (It’s a curious aspect of Wenders’ cinema, the frequency with which it draws from literature.) The distance between Highsmith’s and Wenders’ conceptions is nowhere more apparent than in their respective Ripleys. Highsmith’s is a sociopathic, cool and calculating dandy and repressed homosexual, which made Alain Delon solid casting as Ripley in Purple Noon. Wenders’ Ripley is, well, Dennis Hopper; not exactly the picture of composure, or a person one imagines tending garden or playing the harpsichord at Belle Ombre. Hopper arrived on the set of The American Friend fresh from the Philippines, where he was playing the addled, garrulous war photographer who falls headlong under the sway of Brando’s Kurtz. Though it says something about Hopper’s easily underestimated control over his craft that even during this most toxic, manic period of his career that he managed to shape his Ripley into a distinct creature, tormented by demons yet still able to marshal his wits when faced with a decisive moment.

I would love to see Wenders produce something truly marvelous again… something that forces him to travel off-road, something that forges some serious tension between his too-settled sensibility and the world as it’s changed since he started out on this journey

Closer to the spirit of the source material was Wenders’ Jonathan, an Englishman in France in the novel and a Swiss-born, Hamburg-based picture framer beautifully played by Bruno Ganz in the film. For a guy who would eventually play Hitler, Ganz exudes innocence here—a quality he would repurpose in Wings of Desire. Terminally ill and believing himself to be near death, Jonathan is bamboozled into murdering a Mafiosi. Though initially only tangentially involved, Ripley finds himself sympathizing with Jonathan and becomes his accomplice. The scenes between Ripley and Jonathan are extraordinary, partly because what brings these men together is inherently fascinating, and partly because the actors have such dynamic chemistry: Hopper was the wild Hollywood veteran, a rebel without a cause prone to unpredictable riffing, while Ganz was younger, a European stage actor with limited film experience who spent the shoot feeling out of his depth. If Hopper wasn’t intimidating enough, Ganz was surrounded by giants of cinema: Wenders, uncomfortable with villainous characters, decided to cast all the film’s heavies from a pool of fellow directors: Sam Fuller, Jean Eustache, Gérard Blain, Daniel Schmid and Nicholas Ray. Such casting is catnip for cinephiles, but it is also arguably symptomatic of some of the problems that plague his later, lesser films, both fiction and non-fiction: instead of grappling with the challenges of cinematic storytelling, however loosely defined, Wenders opts to simply fill a film with things he loves, assuming that to be enough.

This strategy works intermittently in The State of Things (1982), which Wenders made while waiting on Zoetrope to allow production to continue on Hammett (1982). The State of Things is itself about a halted production. Again, “nothing happens,” though in this case “nothing” feels more like nothing. The charismatic Fuller is brought back again and is hardly difficult to spend time with. The black and white images of Portugal and Los Angeles, apprehended by legendary French cinematographer Henri Alekan (who shot Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête), are exquisite. There’s great music and great locations. Roger Corman and Viva both turn up in oddball supporting roles. The State of Things is a likeable film that may not add up to more than the sum of its parts.

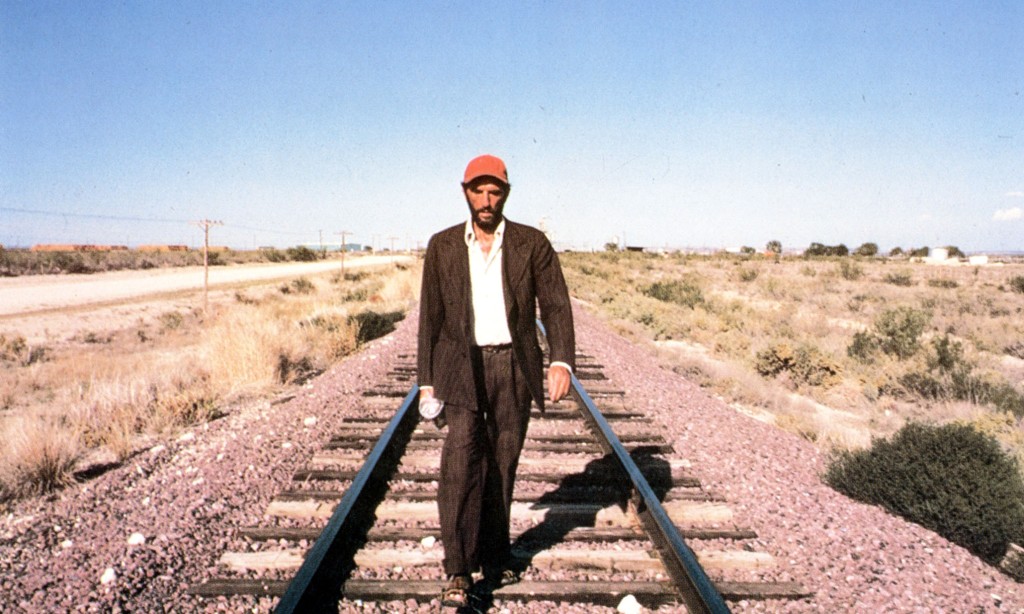

Which is not an accusation one could level at Paris, Texas (1984), the most haunting and emotionally rich work in Wenders’ oeuvre, and an argument for Harry Dean Stanton as one of the greatest actors in the history of cinema. The film’s story can be broken down into a series of relationship studies. It is, in order, about brothers, about father and son, about husband and wife, and finally about one’s relationship to one’s self, about solitude as the last refuge for those incapable of forgiving themselves. The film is immaculately structured yet it was literally made up as they went along. The script is attributed to Sam Shepard, but Shepard had to abandon the project partway through production to play Chuck Yeager, and so that long, incantory, heart-crushing penultimate scene in which Stanton and Nastassja Kinski are separated by a one-way mirror—the most Sam Shepardy thing in an extremely Sam Shepardy movie—was actually written by Kit Carson. Wenders, Shepard, Müller, Carson, composer Ry Cooder, actors Stanton, Kinski, Dean Stockwell, Aurore Clément and Hunter Carson: the project was blessed from the start with a horde of immensely gifted people (Claire Denis was the assistant director, for Christ’s sake). Plenty happens and everything works. Paris, Texas was lighting (over water) in a bottle. Set entirely in the US and infused with American iconography, it’s also the film where Wenders fully confronts the country whose culture and terrain had always had such a hold on his dreams.

Which makes it tempting to regard Paris, Texas as the crossroads, the point where Wenders peaks with his magnum opus and thereafter makes the wrong move. Except that not long after Paris, Texas Wenders reunites with Ganz, Handke and Germany and makes a film about, of all things, angels. Wings of Desire (1987) is where I came in. Sort of. My memory is of it getting regularly aired on A&E when I was a kid. I always caught it somewhere in the middle, with not the slightest idea what I was watching. But it was gorgeous and strangely hushed and I liked circuses and Peter Falk and I really, really liked Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, who perform one of the cinema’s most unlikely songs to have lovers meet to. Because I was so mesmerized by Wings of Desire as a kid I keep returning to it every few years with the certainty that it will not hold up. I keep being wrong.

Wings of Desire lodged Wenders in my consciousness, but my actual awareness of him as an artist occurred a little later, in my teens, in a record store where I came upon a soundtrack with a roster of artists and songs that was surely designed just for me: Talking Heads, Lou Reed, CAN, Patti Smtih, Neneh Cherry, Daniel Lanois, R.E.M., the angelic pairing of Jane Siberry and k.d. lang, Cave and the Seeds, and Elvis Costello doing an overblown but lovely cover of a Kinks song. I bought the soundtrack, obviously, and still listen to it frequently. It seemed impossible to me that a single movie could contain all this great music, but that was before I realized that the movie was either 158, 179 or 288 minutes long, depending which version you had access to. The good news is that the world takes a really long time to end.

By the time I had actually seen Until the End of the World—the 179-minute version, on VHS, alas—the film seemed to me like a supplement to the soundtrack, rather than the reverse. It was as though Wenders’ often luxurious images were wound around this sequence of songs, which in their oblique way already possessed a narrative. In all honesty, given my adolescent habit of snoozing, I can’t say for certain whether or not I ever made it through the whole film, though it didn’t seem to matter much at the time. You fall asleep, you wake up—hey, there’s Max Von Sydow!—and the road trip keeps going.

And going, and going, and going… TIFF Cinematheque’s Wenders series, playing this month, doesn’t follow his filmography much farther than Until the End of the World. We get Buena Vista Social Club (1999), an enormously important document, and Pina (2011), an inventive dialogue with the late, great choreographer Pina Bausch—though this film also inaugurates Wenders’ enthusiasm for 3D, which extends for no discernable reason to his recent James Franco-starring fiction film, Every Thing Will Be Fine (2015). There is in TIFF’s series no End of Violence (1997); no Million Dollar Hotel (2000), with its original story by Bono and its memorably baffled performance by a very unhappy Mel Gibson; no Don’t Come Knocking (2005), a hugely disappointing reunion with Shepard. Would I have had the stamina to attend screenings of all those troubled later films even if they were programmed? My great admiration for the artist who made the masterpieces may not be galvanizing enough to get me through the chaff. Which isn’t to say that we should write Wenders off: bad movies happen if you keep making them long enough. Every thing will not be fine, or at least not every time. I would love to see Wenders produce something truly marvelous again. Not a throwback, not a greatest hits package, but something that forces him to travel off-road, that forges some serious tension between his too-settled sensibility and the world as it’s changed since he started out on this journey. Maybe he needs to find some new way to get lost.

TIFF Cinematheque’s On the Road: The Films of Wim Wenders—along with a sidebar of some of Wenders’ favourite films—runs at TIFF Bell Lightbox until March 17. See tiff.net for details.