Reviews include Irena’s Vow, The Beast, and Before I Change My Mind.

On BAFICI 2021 and Attending Film Festivals from Half a World Away

March 30, 2021

By José Teodoro

As I write this report, the 2021 Buenos Aires International Festival of Independent Cinema, or BAFICI for short, is drawing to a close. I’m trying to decide whether or not I attended. I was a member of BAFICI ’21’s International Critics Jury and saw every film in the festival’s Pan-American competition. Or did I? I’m half a world away from Buenos Aires, perched at my desk in Toronto. Was does it mean to see films at a festival? Over the years I’ve been to a good number of them in Europe and the Americas and have always considered place, climate, screening rooms, scheduling, food, language and, above all, people as integral to the festival-going experience. Festivals, to me, mean conversations with colleagues, often strangers, outside cinemas, in the street, in lobbies, bars, cafés or at parties, where I suck back coffee or booze or shove (hopefully free) food in my face, trying to decide whether to catch one more screening or keep talking to this filmmaker, critic or programmer I just met, who may have some insight into the creative, cultural or political context of the film we’ve just seen and can’t stop gabbing about. These conversations enhance my understanding, embolden my convictions, or change my mind.

Partaking in a festival remotely is less exciting to me. Admittedly, I may be something of an outlier: unlike many people I know I’ve been watching fewer movies, not more movies, during the pandemic. I miss going to the movies—the collective, messy, time-sensitive experience. I generally need to be coerced (or, ahem, paid) to watch movies on this same device where I do my invoicing, check my email and write. But I must concede that this device also allowed me to converse, albeit somewhat awkwardly, via video call with my co-jurors in Brazil and Argentina, and that provided me with a tiny dose of what I’m missing: an international, unpredictable, dizzyingly diverse community united by our engagement with this ever-changing artform.

As it happens, the film to which our jury awarded our prize is one prompted by a viewing experience that has nothing to do with going to the movies. The advent of direct-to-video releases in the 1980s presented an opportunity for a new kind of micro-budget auteur, the sort of single-minded outsider artist who only ever felt alienated by institutional gatekeepers anyway. I’m talking about artists like Manuel Lamas. (I hadn’t heard of him either.) Lamas made a movie called Acto de violencia en una joven periodista. Its title alone, which roughly translates as Act of Violence in a Young Journalist, is gloriously unruly. The movie was always destined for VHS. In fact, it was shot and edited on VHS, a rarified format. (Rarified because it looks like shit and visibly degrades with every transfer.) It’s a movie that draws you in with the audacity of its ambitions and its absolute failure to realize those ambitions, at least in any conventional sense. As decades passed Acto de violencia earned a cadre of devotees in Lamas’ native Uruguay and neighbouring Argentina, while Lamas himself seemed to evanesce into obscurity, along with the VHS tape.

In the first part of Straight to VHS (Directamente para video), the feature debut of Uruguayan writer-director Emilio Silva Torres (who was, incidentally, born the same year Acto de violencia was released) a number of filmmakers and movie nerds testify their love for Lamas’ ramshackle “thriller/documentary/rom-com/supernatural drama.” They praise its clumsy camera placement, awkward performances, overburdened plot, and flourishes of accidental avant-gardism. Silva Torres’ film initially comes across as an amiable documentary celebration of offbeat cinephilia. It’s only in its second, longer section that Straight to VHS proves to be about something else altogether. It’s not really a documentary about cult movies. It’s not even really a documentary. What Silva Torres has created, with considerable grace, craft and imagination, is a study in obsession, one fuelled, like all obsessions, by elusiveness: resolution is always tantalizingly out of reach.

An editing suite surrounded by an expanse of darkness, a phone booth in the middle of a forest, an intersection in Ushuaia: Silva Torres takes us to a number of strange locations while following an ostensibly straightforward pilgrimage. He makes appointments to meet with Acto de violencia’s cast-members, only to have them abruptly and mysteriously end their correspondence. He makes contact with a handful of people who knew Lamas and describe him as alternately charismatic, manipulative, eccentric, heroic, misogynistic. One especially memorable interview subject claims that Lamas saved him from the depths of despair. Lamas becomes a phantom. His monstrous qualities begin to overshadow his appealing ones. But Silva Torres cannot let go of his quest to somehow know Lamas. With its echoes of Inland Empire, not to mention several novels and stories by Roberto Bolaño, there is a point in Straight to VHS where Silva Torres seems to slip into a labyrinth of his own devise. It’s a journey I’ll refrain from describing further, since surprise has been so carefully built into the film’s structure. I hope Silva Torres recovers from his chilling misadventure. I’m eager to see what he’ll do next.

Shot on 16mm, US director Jim Finn’s The Annotated Field Guide of Ulysses S. Grant is both a work of historicism and a reflection of our present era of monument-toppling and reclamation. It’s a travelogue of Civil War sites, a geographical survey of cotton fields, cannonballs, tombstones, visitor centers and wax museums, with stops at the titular ex-president’s Ohio birthplace and a motel named after Jefferson Davis. Images of these locales are juxtaposed with an ongoing voice-over featuring citations from Ta-Nehisi Coates and Henry Louis Gates and tales of slave rebellions, feral hogs eating corpses, or a man drinking water from what will become his own grave. There are also title cards, trading cards, illustrations, stop-motion animation of historical board games, much of which is rather twee and a little too kitschy and detached to command one’s attention as fully as the subject matter demands.

Like Field Guide, Concert for the Battle of El Tala, from Argentine director Mariano Llinás, is also concerned with re-examining historical conflicts, though in this case the framework is a studio performance of Gabriel Chwojnik’s epic musical adaptation of the memoirs of General Gregorio Araóaz de Lamadrid. Where Llinás’ 808-minute La flor (2018) was sprawling, delirium-inducing, multi-narrative and multi-genre, the 64-minute Concert is compact and, by comparison, stylistically hemmed-in, with black-on-white title cards offering commentary, written in verse, on our diminished capacity to recognize the ghosts of history inhabiting our national landscapes, interspersed with images of the musicians at work, a beguiling cat, and a dog-eared copy of Sarmiento’s Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism. The film is inventive, playful, beautifully shot and edited, and only slightly tedious. Like La flor, Concert proposes that the pleasures of cinema and literature can overlap and harmonize in enchanting new ways.

The exact opposite of inventive and playful, yet a paragon of tedium, Argentine director Ernesto Baca’s quasi-mystical road movie Israel was made in Mexico and seems determined to run the spectrum of Mexican cliché, with ostentatious appearances by the Virgin of Guadalupe, the Torre Latinoamericana, pilgrims and folkloric dances, estampillas religiosas and casual police corruption. This trippy travel-brochure exotica is combined with a barrage of equally over-familiar conventions of experimental cinema: jump-cuts, flamboyant sun flares, reverb-heavy sound effects, psychedelic superimpositions, a visit to a cemetery that reeks of Easy Rider, and Christ imagery that reads as warmed-over Jodorowsky. To be fair, the compositions are handsome and there is a pleasing sense of rhythm to the editing (courtesy of Roman Noriega). Which is to say that any three minutes of Israel is pleasant enough to watch. (The film’s runtime is 64 minutes.)

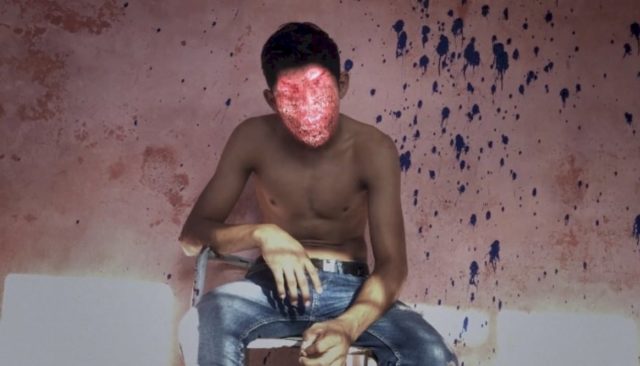

A more compelling, meaningful, rigorous and relevant example of an outsider working in Mexico is Los Plebes. Directed by Venezuelan filmmaker Eduardo Giralt Brun and Mexican rapper Emmanuel Massú, this observational documentary is the result of months spent in Culiacán, Sinaloa, a place, like so many in the Mexican north, where most citizens are more comfortable with sicarios than police. Giralt Brun and Massú profile a handful of workers, nearly all of them disenfranchised adolescents already ensnared in a milieu of organized crime from which one rarely gets out alive. In order to protect their identities, Giralt and Massú ensure that actual masks or digital masks, applied in post-production, are worn by all their subjects—all except one, a young ex-con whose compulsion to bare his visage and invite the filmmakers into his world is complicated and undeniably moving. An early scene finds him in his home, a shack with nothing to bar entry, draping a sheet over a rifle in case his grandma comes around. When he’s not handling guns he’s usually handling an extremely cute puppy he’s looking after. He describes returning home from jail and being unable to sleep in his own house: his body had been freed, he explains, but his mind was still incarcerated. Given the chance to start over, he would be happy to be a farmer or carpenter, but he was recruited so young, and is now destined to remain an expendable, impoverished foot-soldier in an endless war and a culture of systemic nihilism where tit-for-tat killings proliferate.

I’ll end this survey with another film about youth that’s less incisive than Los Plebes but, at least, more hopeful. As a long-time Sonic Youth fan, the first thing that grabbed my attention in Brazilian director Gustavo Galvão’s We Still Have Deep Black Night was an opening title that credited SY alumni Lee Ranaldo as soundtrack producer, working with songs by a band called Animal Interior. It turns out that the film’s music is, in fact, its strongest asset, but there’s much that’s endearing in this portrait of Karen (Ayla Gresta), a young singer-trumpeter raging against Galvão’s native Brasilia, whose architectural austerity becomes a fitting backdrop for Karen’s struggle to forge a path making innovative rock while most of her colleagues are giving up, getting soul-deadening jobs or, in the case of her boyfriend, moving to Berlin. Karen eventually follows him, though the film, which overstates its status quo, is nearly half-over before she does this. For a film about restlessness, youthful tenacity and the visceral thrill of rock and roll, We Still Have Deep Black Night is curiously lacking in momentum and drive, but when music is being performed, especially by the dynamic post-rock outfit Karen hooks up with in Berlin, the sense of release and artistic discovery is infectious. Karen is not especially articulate, but she seems to be searching for her own narrative, something to get swept up in and validate her talents, something to endow her with purpose. This is not so different than the feeling of the film itself, which, whatever its shortcomings, reminds us that sometimes the best thing any work of art can aspire to is to apprehend a vibe, ride an exhilarating wave, make a racket, kick out the jams, even if when the immediate rush is over there’s nothing left to do but sleep it off, wake again tomorrow, and keep dreaming.