Reviews include Deadpool & Wolverine, Doubles, and Mountain Queen: The Summits of Lhakpa Sherpa.

25 Years of Highway 61

September 28, 2016

by Tina Hassannia

An understatement: Bruce McDonald likes making road movies.

Weirdos, which premiered at TIFF just a couple of weeks ago, is the latest add-on to an original trilogy that included Roadkill, Highway 61, and Hard Core Logo. These films use the genre to bring together — and tear apart — a variety of colourful characters, all on respective journeys (both physical and spiritual), each trying to make sense of their place in the world.

Perhaps that’s not an entirely Canadian experience. But in McDonald’s films, there is a Canadian sentiment of feeling adrift in one’s identity; sleepy, peaceful stretches of asphalt are turned tragic, or entertaining, or cosmic, depending on the story and plot turn, and form a common visual theme. Another pattern found in McDonald’s films is music, not just through the use of famous songs but also through greater and broader ideas about the art form, typically inserted through musician characters, elements of performance, the friendships and hardships of being musicians or knowing musicians. McDonald seems to have instinctively known that road movies and music naturally go together. What else is there to keep us entertained on the empty road?

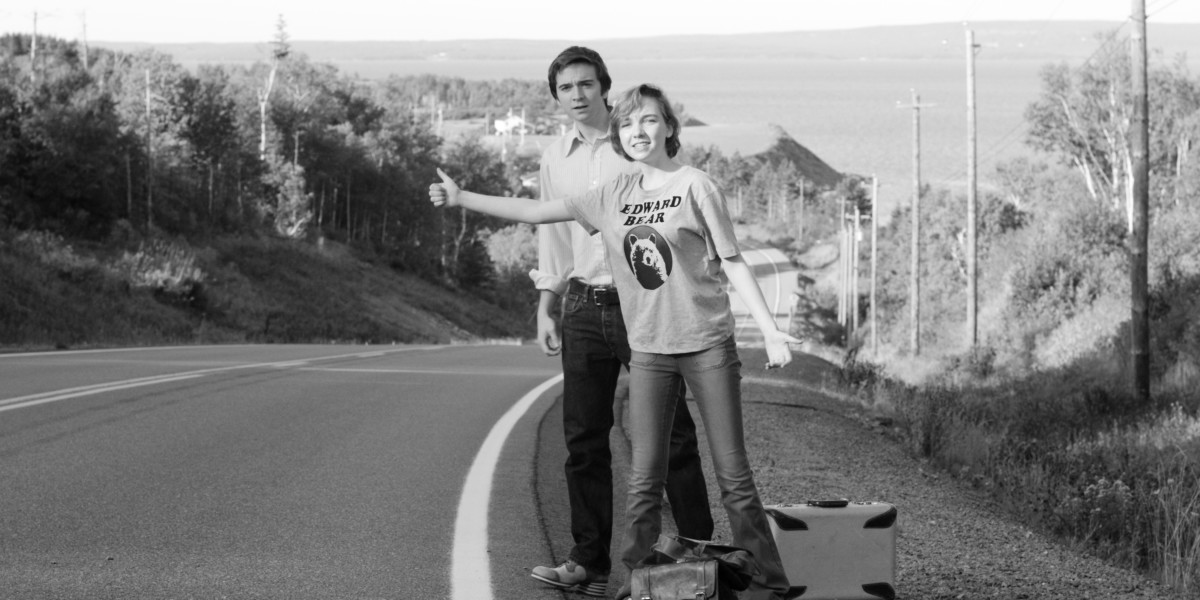

While Weirdos premiered at this year’s festival, Highway 61 screened a quarter of a century ago at the Toronto International Film Festival. It stars Don McKellar as Pokey, a milquetoast barber who half-heartedly wants to be a jazz musician; the walls of his barbershop are adorned with a shrine to the greats. Pokey’s a lost dreamer, in other words. He’s granted an opportunity to finally see the great land of America and the historic New Orleans when he meets Jackie (Valerie Buhagiar), a “roadie fugitive” trying to hitchhike to Louisiana while also transporting the body of her dead brother for a funeral.

That’s the official story, anyway. As the audience learns early on, Jackie’s busy trying to smuggle drugs across the border using the corpse. And so the journey begins, from Thunder Bay to New Orleans, along Highway 61. For Jackie, it’s about the final destination. For Pokey, it’s about being a Good Samaritan and finding a new perspective on life. The film’s title is as much a reference as it is a tribute, as McDonald follows Bob Dylan’s tradition in naming his own art after the Blues Highway. A reference to Dylan here, a Ramones song there, Highway 61 is the kind of strange little film that earned English-Canadian cinema its oddball reputation in the 1990s (for an even weirder film that came out the same year, watch Atom Egoyan’s The Adjuster).

Music references sharpen the film amidst its inchoate eccentricity. There are a few incisive moments that demonstrate a strongly outsider, Canadian take on the myth-making and larger-than-life personalities so commonly encountered in the music industry. Pokey, for example, writes a postcard to his French-Canadian friend, where he describes via voice-over narration his joy of sight-seeing while on the road. The image that’s matched with this particular bit of dialogue is a brick-house window featuring a bored house-cat on its ledge. An American landmark, indeed. The irony, however, is quelled when we find out why Pokey is so excited to see this particular house: it’s supposedly Bob Dylan’s childhood home.

On their trail is Satan (Earl Pastko), a suited man too confident for the thick brows that crowd his face, who claims people’s souls by having them sign contracts in blood for whatever they want. He’s tickled by the triviality of his victims’ dreams: a bottle of bourbon, a twenty-dollar bill. Is Satan real? Or is he just some lunatic who happens to convince the audience of his powers in a Bingo-set scene where he wins round after round through sheer “luck”? Or perhaps Satan is just a referential figure in the larger scheme of the story, representing the record-company executive who promises musicians dreams on paper in exchange for their souls. Among Satan’s victims is Louise Watson, a girl who’s been told repeatedly by her dad (Peter Breck) that she and her sisters are going to become famous pop-stars one day. Despite his reverence for their talent, Mr. Watson doesn’t hold back from telling any one of the girls when they’re out of tune or not performing up to standard. There is no better song to introduce us to the Watsons and the saccharine-sweet mirage of wholesomeness and optimism than The Archies’ “Sugar Sugar.”

One of the more out-of-place scenes involves Jackie’s rich and famous musician friends, a couple cooped up in a Xanadu-like mansion with a butler whose long hair tells us exactly what kind of music he likes. They’re slowly going insane and trying to rope Jackie and Poker into their madness, climaxing with a wild goose chase (or should I say, chicken chase). The scene is set to Tom Jones’ “It’s Not Unusual,” because, I guess, when you make friends with famous people, pistol-hunting chickens in a mansion is fairly commonplace.

These examples are just a few of the many images of Highway 61 that illustrate some of the harried tendencies apparent in music—its self-destructive nature, the delusions and pipe dreams and convictions. Outside of these ideas though, more than anything, Highway 61 is an ode to the anxiety of identity — particularly a Canadian, English, white and male identity. Poker can barely play his instrument, he’s gullible to Jackie’s lies, and he can’t even shoot a chicken once he corners it. 25 years ago, Bruce McDonald showed us a shadow of a man who lives through the dreams of others, those who dare to be daring, just south of the border.