Reviews include Irena’s Vow, The Beast, and Before I Change My Mind.

Anatomy of Criticism: A. O. Scott on his profession, his new book, and everything in between

April 6, 2016

by Brian D. Johnson

Film critics don’t tend to read each other’s reviews. You don’t want read them before you write your own, and after … well, you’ve moved on. When I was writing about film on a weekly basis for Maclean’s, I’d skip the Friday dispatches, but I would often read the essay-ish pieces by film critic A.O. Scott in the Sunday New York Times. I felt we had similar sensibilities. And I was always trying to beat him to the punch in spotting trends in the cinematic Zeitgeist. So it was with considerable interest that I plunged into Better Living Through Criticism: How to Think About Art, Pleasure, Beauty, and Truth.

Scott’s new book is a wildly ruminative inquiry into the nature of criticism: its evolution, contradictory impulses, and complicated relationship to art—not to mention the far-fetched notion that writing it can be a real job. Scott’s book is an off-leash park of intellectual play, littered with bon mots and saturated with comic irony. Spinning off a Susan Sontag slogan that “in place of hermetics, we need an erotics of art,” he can’t help but ponder how his line of work may relate to the oldest profession: “If criticism is—or should be—a way not just of expressing love for art but also of making love to it, what does that make the people who do it for money?”

A.O. Scott is a chief film critic at the New York Times, and Distinguished Professor of of Film Criticism at Wesleyan University. He spoke to me by phone from his home in Brooklyn, N.Y. late on a Sunday afternoon.

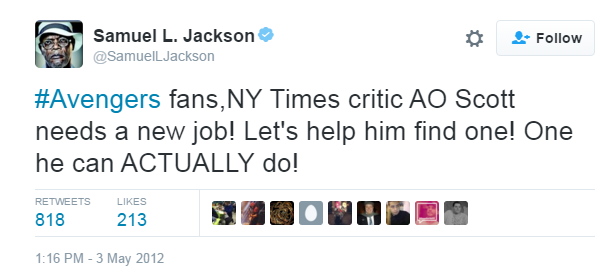

Brian D. Johnson: Tony, your book covers the whole enterprise of criticism—ranging far from film, into philosophy, literature and art. But you’ve also delivered an extended review of your own profession, and it’s a very mixed review. You argue with yourself in Socratic dialogues. You constantly play devil’s advocate—one who’s rather critical of his client. And speaking of the devil, you even find an analogy for the act of criticism in original sin, calling it “the snake in the garden of what should be our simplest pleasures.” So what brought this on? In the book, the inciting incident appears to be a tweet by Samuel L. Jackson in response to your review of The Avengers, which you dismissed as “a snappy little dialogue comedy dressed up as something else, that something being a giant A.T.M. for Marvel and its new studio overlords, the Walt Disney Company.” Jackson urged his Twitter followers to find you a new job, “one he can actually do.” Was his tweet the critical act that caused you to reexamine your role as a critic?

A.O. Scott: Not quite. I had already begun thinking about it, and was signed up to do it. I was just reaching a point in my career as a critic where I felt it might be useful to figure out what I was doing, and to give some account of it. I was also very struck by the sense of imminent or actual crisis around criticism in the year or so before that Avengers review. It was a time when things were looking very dire in print media and very utopian in social and digital media. And there was a lot of discussion about the end of criticism, the death of criticism—either lamenting or celebrating the fact that now everybody has this wonderfully democratic situation where we wouldn’t need critics any more and everyone could just do their own thing and like what they like and share it on Facebook and rate it on Yelp. So the original motivation was to wonder, if this was really a crisis, what would it look like if criticism were to disappear? Was it even possible for criticism to disappear? And it was there that I kind of got the idea of trying, as I do in the book, to make a distinction between the work that professional critics like us do and the broader cultural activity of criticism. So the Samuel L Jackson incident, the Twitter beef, was a moment that helped crystallize that, and helped me think about the problem that so many people seem to have with just the idea of criticism.

BDJ: Jackson’s tweet broke the fourth wall that stands between the critic and the thing being criticized. Does that happen to you very often, where the movies talk back?

AOS: Almost never. That was what was so striking and so surprising about Jackson tweeting the way he did. It generally doesn’t happen at all because either I’m writing about huge commercial movies that couldn’t care less about what I have to say—as we’re recently seen with Batman v Superman, critics’ opinions about blockbuster franchise entertainment don’t amount to a hill of beans. I’ve noticed that theatre critics, or restaurant critics, and book critics get a certain amount of public pushback from the people they write about. Sometimes Broadway producers will take out full-page ads attacking theatre critics; sensitive chefs will complain about how they’ve been treated by restaurant critics. Movie criticism seems a more immune to that. It may just be a bigger industry and one that has less of its own stake in what critics say.

BDJ: And there are so many voices. Even though you’re one of America’s most eminent film critics, you rarely have the power to make or break a film. But a theatre critic can break a play or break a restaurant in print, which is frankly a power I wouldn’t like to have.

AOS: I’m very happy not to have it. I’m very happy not to feel that burden because I I’m free to say what I want to say . . .

BDJ: Without worrying about the consequences.

AOS: Yeah, and ruining someone’s life. Because even the worst movies or the greatest failures are the product of a lot of usually sincere and hard work. I like the fact that the power of a film critic in my position is more positive than negative. Sometimes I have felt that I’ve helped a smaller film reach a larger audience than it would have, but there isn’t a sense of having that kind of power. And one of the things that I do try to argue against, or at least demystify, in the book is the whole idea of critical power. The idea that we’re a priestly cast of vested cultural authorities who are trying to direct the public taste.

BDJ: In the book you make a strong case for the necessity of criticism—even the inevitability of it—and the universality of it. You make the case it’s an art form when done right, and whether consciously or not every artist is also a critic, building on or destroying the art that came before it. But you do make a distinction between the critical intelligence contained in, say, Keats’ Ode on a Grecian Urn, and what you call “the sneering and scrabbling of everyday reviewing.” Which brings me to your musings about the actual job—”how exactly is that a job?” as you ask. Or, more to the point: “What kind of grown man sits through Kung Fu Panda scowling and the screen and taking notes?” That’s your rhetorical question. Can you answer it?

AOS: I guess it’s a rhetorical question. It’s also a complicated question, because there is part of me that agrees with the idea that it maybe shouldn’t be a job, or that professional critics are performing a function that really is a much more common and universal role. It’s just one of those weird things about the division of labour—we all have the potential to be artists, to be critics, to be all kinds of things, but only some people actually do that with most of their working time. In my own case, it is the result of a lifetime of interest and enthusiasm about movies, and other art forms. It’s always interesting to me when critics are said to despite the art that they write about, because it’s almost always the opposite, the motive for being a critic. You’re fascinated and enchanted by these movies. You want to think more about them, explore them, figure out how they work. So for me it has been a lifelong interest in film as a vehicle for ideas and stories and a source of information about the world— and also a lifelong interest in writing. My earliest ambition that I can recall was to be a writer and criticism has been the way I’ve managed to fulfill that ambition.

BDJ: That was my entry point as well. I’ve never identified primarily as a critic, always as a writer. I came out of journalism landed almost by accident into a film critic job. In the book, you recall that when you were young you’d read about artists and be fascinated by them without ever needing to see their work. You just loved to read about them. Which gives credence to the notion of criticism as a stand-alone literature.

AOS: I’m not sure it’s all that uncommon. Like a lot of people when they’re growing up, I didn’t have access to all the stuff I might have been interested in. I couldn’t travel wherever I wanted to go, I couldn’t see any movie I wanted to see. But I was a devoted reader of the Village Voice at the end of high school and through college. I was really interested in the paper’s coverage of the experimental theatre and downtown art scene in New York. The way various critics evoked that scene, especially Cynthia Carr, I would always read about it.

BDJ: In writing a review, I always assume the person reading it may have no interest in seeing the movie. And that writing has to be good enough on its own.

AOS: Right! And the only thing you can control, in a way, or have some influence over, is their interest in reading your review to the end. Whether they see the movie or not, you want to hold their interest and entertain them for as long as it takes to read it.

BDJ: In the book you make a real virtue of uncertainty, and fallibility. You write that “it’s a sacred duty of every critic to be wrong.” If indeed everyone is a critic, the world seems to be divided between those who know exactly what they think and those who never stop trying to figure it out. I’m in the latter camp. Half the time I walk out of a film not quite knowing what I think, and need to write to figure it out. With the obvious failures, you can tell before the movie’s even over. Same with the things that blow you away—you just try to figure out a way of conveying the experience. But so many films are in that middle ground. And I’m struck by how readily you cop to your own uncertainty, because it’s not something a lot of critics are willing to do.

AOS: No, and it’s something that some of the critics of this book have found fault with. I think you described it very well: there is the type of people who believe that the critic’s job is to be certain and to help the reader achieve a kind of certainty. Not only to take a stand and defend it, which we all do, but to walk in to a movie with a set of clearly articulated standards and ideas that will then be applied to the movie. My own practice is much more open and more uncertain. I want to see what this is and figure out on its own terms how to think about it, then to work through my own response. And the critics I like to read are always those where you can feel the thinking going on. You feel you’re in the presence of a mind that’s working out its own point of view rather than proceeding from a position of certainty and trying to argue that. So almost all of my writing is some kind of dialogue with myself and working out of a problem. You don’t want to be too self-indulgent about that or too self-absorbed. Your job is still to convey something about this movie, about this other thing, to people who are interested in it. But I find that the way to do that is to work through my own confusion or ambivalence, or my own indignation and impatience, or my own enthusiasm. It’s a great challenge and when you really are blown away by something, it’s one of the most exciting things to give an account of that experience and explain how it happened. And why it mattered you to. Without falling back on a lot of empty rhetoric, without saying this is a masterpiece, without just filibustering and throwing adjectives at it.

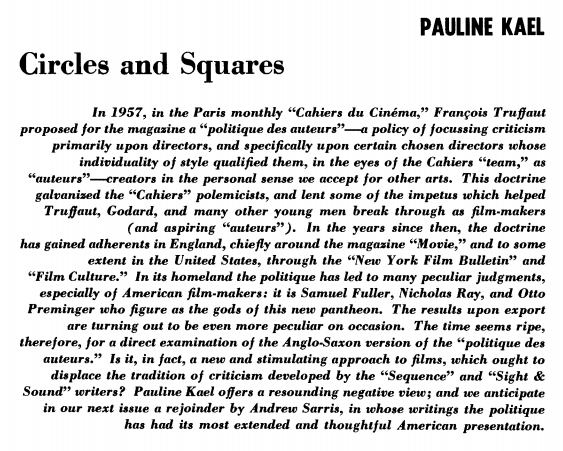

BDJ: When you go into a film, the first job to open yourself up to the experience that the film is trying to produce. To try to fall under the spell, while being observant. If find those who cling to the auteur theory—at festivals they always refer to new films by the last names of the directors [the new Loach, the new Winterbottom, the new Sokorov], they immediately judge the film within their a pet theory about director’s previous work.

AOS: It is an a priori judgment, cutting off access to some of the areas of experience. It’s funny, I’ve just been teaching Pauline Kael to film studies majors and reading her amazing and extremely harsh takedown of auteur theory, that essay “Circles and Squares,” where she says exactly that. Where this kind of very narrow path of judgment has been set out. You’re already prejudged the artist, and you’ve designated this person as a great, or as a lesser artist, then your judgment of the film will confirm that prior judgment. It will be a lesser or greater example of the great artist’s art, but mostly the work of judgment has been laid out for you in advance. And she says this is an approach to criticism that is meant to neutralize the role of the critic, and I think that’s right. The real difficulty is to be open to something new, to suspend your prejudices and judgments and then at the end of it still have an argument to make, and not throw up your hands and say, “Well, some people will like this, some people won’t.” Which is always true. Every review could be that. You have to put down your own marker. But you have to be transparent about the process that led you to that judgment.

BDJ: Speaking of judgment, did you read the reviews of your book?

AOS: I read as many of them as I could find. People are very kind about pointing me to them on Twitter. [laughs]

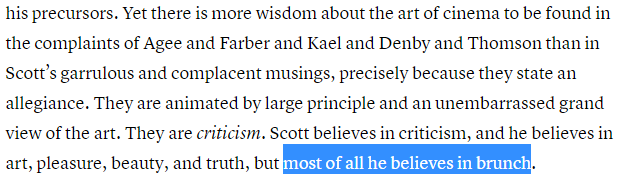

BDJ: Critics reviewing a book on criticism can get very meta. And when critics take obvious pleasure in attacking you, it like cannibal incest. I just stumbled across the ferocious attack on you in The Atlantic by Leon Wieseltier.

AOS: Which is really one of my very favourites. The book is a bit of a Rorschach blot, because some of these reviews are very revealing of the critics’ own ideas or neuroses or preoccupations about. There was one review in The New Republic that was all about my supposed power and the power of critics, and was very impatient with me for not writing more about my own power. And I thought, well this is not really my problem; this is not really what my book is about. But it was interesting And the Wieseltier review in the Atlantic was a great delight to read. You were just saying a minute ago about the two camps—the people who proceed from certainty, and the critics who proceed through uncertainty. I’m very much in the latter camp and Leon is very much in the former: he’s a man who loves to parade his own certainty in prose whenever he can and also is very attached to his own role as the only furious man in America. So for me to be his scapegoat of the month, and to represent everything shallow and foolish and dilettante-ish and unserious in the culture at that moment, I took as a great honour. It was also a relief. Being familiar with his work, and knowing him slightly, if he had loved the book I would have felt like I had done something wrong.

BDJ: He took such delight in attacking you. He called you “a critic without a cause”. He dismissed your book as “a jovial blur of local perceptions and easy paradoxes.” He mocked your open mindedness as “the levelling voice of a wised-up idealist.” And he even assaults your eloquence, saying “the general impression is one of uncontrollable articulateness.” Aren’t you hurt when someone lays into you like that?

AOS: Well, not in this case. If he was someone who hadn’t made a career out of being such a complete pompous ass for the last 30 years, I might think that. I don’t want to get into an ad hominem battle with Leon Wieseltier, who has also accomplished many admirable things in the world of letters, certainly as the editor of the back of the book for the New Republic, but I do think that his temperament is so extreme that I can only laugh. There are other reviews that bothered me more, from people whose judgments are a little harder to shake off. When Nathan Hiller at the New Yorker said that the book was a mess, that hurt my feelings. Because I didn’t think it was a mess. He was sympathetic to me and felt the execution of the book was wanting. I’ve said that about various filmmakers and I’m sure that that hurts.

BDJ: Andrew Sullivan called him “a connoisseur of personal hatred.” So I guess he was just doing his job. But I couldn’t believe when he ended it the review by questioning your belief in anything, and saying, metaphorically I presume, that “most of all [you] believe in brunch.”

AOS: Well, that was incredible. I actually have written a letter that would be published in the next Atlantic where I respond only to that, which I felt was close to libelous. There’s nothing in the book about brunch. There’s no citation in the index for brunch, and oddly enough one of my friends at the newspaper, the food editor and former restaurant critic, Sam Sifton, who is a strong anti-brunch polemicist. I’m a dedicated anti-brunch person. I think that there’s breakfast or there’s lunch, and if you have a bloody mary with your eggs benedict that’s fine, but it’s got to be one or the other. I just thought that was outrageous grandstanding.

BDJ: He was so venomous he could be a film critic. But he’s from the literary world. And you write more about literature in your book than you do about film. Were you trying to escape your day job?

AOS: I wanted to write about criticism broadly as I could, and in some ways it was an escape from the day job and in some ways it was going back to earlier professional incarnations. I was a book reviewer before I was a film reviewer, and my academic background is in literature. I also found there were more examples available to me in other art forms. Film is a very young art form and film criticism is a very young form of criticism—you can go back 50 or 60 years. So when I found myself engaging these bigger questions about taste and beauty and aesthetic experience, I found there was a deeper body of writing out there in literary criticism—also in writing about visual arts—so as I pursued the project it diversified and got me away from film. The idea was never to make it primarily focussed on movie criticism. But it’s written from the perspective of someone who writes about a popular art form. The Samuel Jackson anecdote that begins the book is a particular thing that happens to people who write about popular art. There are different attitudes that critics have—and relations with audiences and artists—in classical music, art or other disciplines.

BDJ: Film critics are a particular breed. We complain about our ranks being laid off left and right, but film is one area that still has more people employed with full-time jobs reviewing art than any other area. Much of the discourse of film criticism came out of the upheavals of the ’60s and 70s—when exposure to European cinema and European Marxism went hand in hand. And it wasn’t just about the movies, but about the times. Now a lot of younger critics come out of film school very specifically focussed on film.

AOS: I’m from a middle generation. I see a lot of younger critics who are products of a cinephile culture, utterly consumed with film. I was not single-minded in that way. At the same time, there’s an even younger generation coming up for whom film has been reincorporated into a more varied cultural diet, partly because of the rise of television and the change in viewing practices. I see it in my own students. In my film studies class, we talk about Antonioni and we talk about Broad City. Not that it’s all equivalent, but I find more that film critics in their 30s and 40s are hard core cinephiles and those in their 20s and 30s are more interested in the social and political aspects of film and its connection with other kinds of popular culture. For me I come at it from a more eclectic set of interests. I became a film critic quite frankly by accident. I was mostly a book critic and doing other kinds of arts journalism, and as one does, knocking around from one editorial job to another. I got a call from the New York Times that was looking for film critics and trying to find someone off the beaten track—I was certainly that—and they ended up hiring me. That was a huge surprise to everyone, including me, and certainly to every other established film critic who wanted the job. As with most writing careers, journalistic careers are a series of zigzags and accidents and surprises.

BDJ: If you have to settle on a beat, the reason I liked film is that it’s as big as the world is wide.

AOS: Endless variety, and that’s the thing that I still find so exciting about it. Everything—politics, sex, history, every aspect of human experience and every part of the world will show up and give you an opportunity to write about it.

BDJ: At festivals film criticism gets incredibly concentrated. I haven’t seen you at Cannes or TIFF lately. For you, is a festival is a good place to see films?

AOS: I have mixed feelings about the festivals. I burned out on it a bit, and didn’t like being away from my family. So I go to Telluride every year with the family. And enjoy that. There is often a distorting effect when you see so many movies packed together and in such a bubble surrounded by other critics and industry people. I think every critic has found this: the movies look very different. A movie that seemed a little disappointing in Cannes, when you’re there expecting masterpieces every day, when you see it in February at a press screening before it opens, it can look pretty damn good compared to everything else that surrounds it.

BDJ: Last question: are you writing a new book?

AOS: I’m putting together a collection of film writing, and there are some threads in this book that might be worth following, but it’s too early to say. The fact that I managed to finish this one does encourage me to think I could do more. I have to say, it was fun to do and it’s been really interesting, and mostly fun, to see it go out into the world, to see what people make of it.