Reviews include Irena’s Vow, The Beast, and Before I Change My Mind.

At Sundance, Portraits of an Ugly America

January 29, 2019

Park City is a pretty town. The American films playing there, however, reveal an ugliness elsewhere.

In A24’s sweaty, slippery, unabashedly redneck The Death of Dick Long, pockets of rural Alabama are skewered by Swiss Army Man co-director Daniel Scheinart and screenwriter Billy Chew in a shaggy-dog crime comedy that plays like a Fubar film fuelled by Pabst Blue Ribbon. Save for a charmingly average cop (Alabama’s finest?) who stumbles towards the truth behind Dick Long’s murder, no one in this film is particularly bright, save for a few fun examples of hick ingenuity (example: How do you cut grass on a hill? Tie a rope to your lawn mower, of course).

The Death of Dick Long ends with its characters Zeke and Earl (oh yes) performing an acoustic rendition of Nickelback’s How You Remind Me, which becomes a sort of yokel national anthem: Never made it as a wise man; I couldn’t cut it as a poor man stealing.

After films like Dick Long and many others on the Sundance 2019 slate, I continued to return to the same line of questioning: Is America doing okay?

Somehow, another Zeke shows up in US Dramatic entry Them That Follow, an Appalachian gothic about a similarly sweaty church of Pentecostal snake handlers. I’m not entirely certain what Jim Gaffigan and Olivia Colman are doing playing worshippers in this myopic religious community, but the flat, unremarkable drama surrounding the pastor’s daughter’s dark secret is a victim of bizarre casting and self-evident narrative beats. I mean, c’mon: If you play with snakes, you’re going to get burned, and we’re left with another depiction of backwater bumpkins.

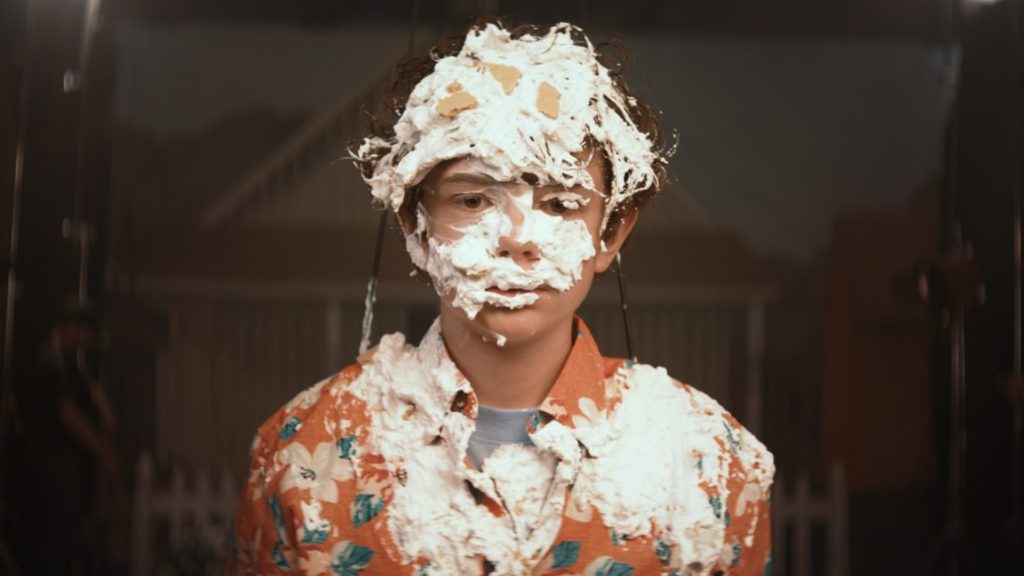

Thankfully, there’s no Zeke in Honey Boy, Alma Har’el and Shia LaBeouf’s psychoanalysis of LaBeouf’s troubled relationship with his alcoholic father. But Zeke, whoever he is, perhaps lives on in spirit: Playing a facsimile of his deadbeat dad under a wig and significant layers of make-up, LaBeouf rewinds the tape on his life as a child actor, setting us in a trailer park of broken dreams and sex workers.

The film isn’t great, and I’d wonder if we’d care at all about this poverty porn-esque memoir if it didn’t explain at least on some level LaBeouf’s trajectory of becoming a lovably unhinged artist in the last decade or so. But it does, and becomes an experiment that feels admirable, at times even profoundly sad.

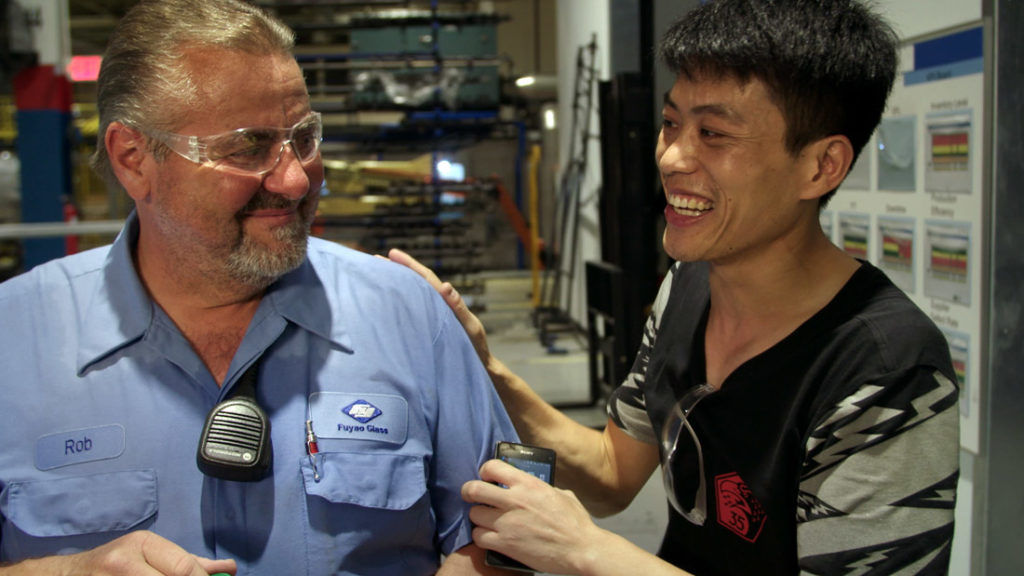

Because it is a snapshot of reality, perhaps this year’s most difficult portrait of the nation’s day-to-day is American Factory, Julia Reichert and Steven Bognar’s unbelievably successful documentary about the new-ish Fuyao Glass America plant in Dayton, Ohio. I say “successful” with astonishment because the film truly is a revelation: When a Chinese billionaire buys a defunct General Motors plant and resurrects hundreds of industrial jobs, the film provides unparalleled access to factory floor conversations—often involving Fuyao’s no-nonsense Chairman—about the deep-seated stereotypes of American labourers. In other words, the Chinese Fuyao workers are taught to expect their foreign colleagues as lazy, unsophisticated, and generally simple-minded. C-suite executives say this on camera.

The filmmakers travel between the Fuyao in China (where workers live in what feels like a corporate city) and the Fuyao in Ohio, and the differences in work culture are… terrifying. The Chinese Fuyao employees sing songs celebrating the company and how they’ll work and smile along the way; the Americans chant pro-union ditties while they scrape by on sub-standard salaries. American Factory follows this thread, leading to a vote on unionization, which fails by a landslide. The majority of Fuyao Glass America employees just want to keep the (underpaid) jobs they have.

Really, the documentary plays like the before and after of one of those cringy Walmart employee pep talks, and it’s capped off by a wince-inducing scene: In a rally to raise spirits, one Fuyao China executive tells his American counterparts that they will “make America great again,” a now awful catchphrase that dumps salt on a jagged wound.

Yet America, despite these portraits of mediocrity, is too resilient to be defeated. And it’s in Rachel Lears’ Knock Down the House, a documentary that primarily follows Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, that we see a nation willing to bounce back. They say documentaries are only as good as their subjects: Were that true, Knock Down the House would be one of the greatest documentaries of all time, mostly because AOC’s on-camera personality is mediagenic to an insane extreme. She’s wonderful to watch, as are her fellow political insurgents trying to launch grassroots political campaigns. If these women are the future of politics, the outlook is blindingly bright.

I mention this film because, at the end of its sub-90 minute feel-good, flag-waving journey, memories of Sundance began to fade back into the realm of fiction: In other words, I was reminded of the good in America, its potential, and what it can do to recover.

— Jake Howell