Reviews include Superman, Apocalypse in the Tropics, and To a Land Unknown.

Circling the Coens: An Interview With Adam Nayman

November 19, 2018

“I don’t think they think Barton Fink’s a greater writer, but I think they think Bob Dylan’s pretty great.”

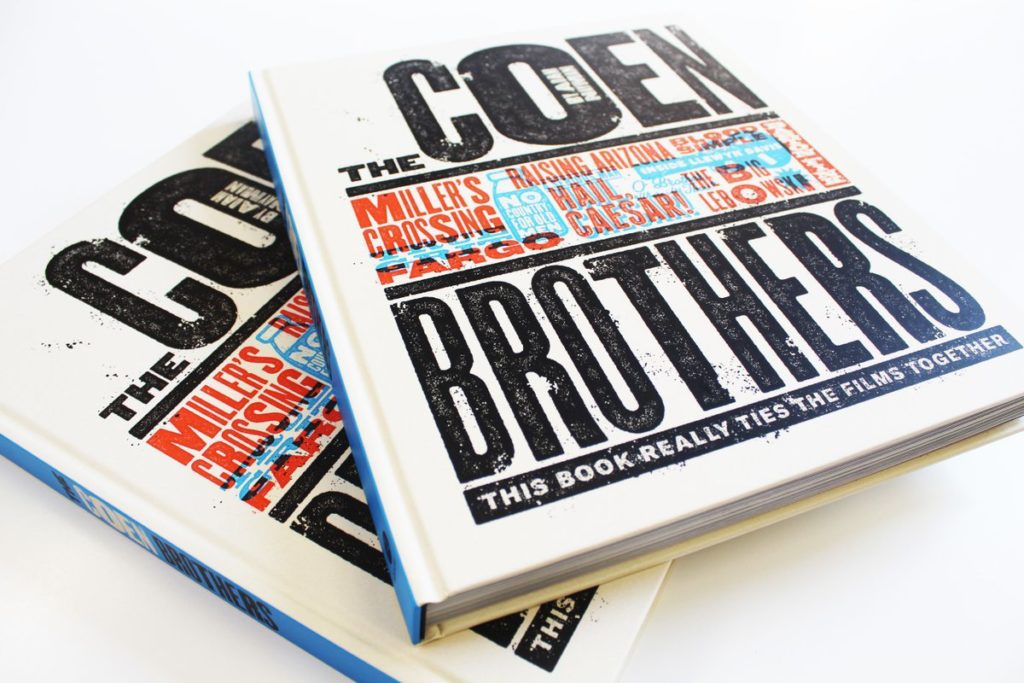

Early in Adam Nayman’s The Coen Brothers: This Book Really Ties the Films Together, the Ringer columnist, Cinema Scope editor, and TFCA member points to the filmmaking duo’s first film Blood Simple as a wellspring for the filmmaking duo’s curiously recursive brand of originality. For Nayman, the brothers leave one of their earliest calling cards via their fixation on the circularity of violence and what he calls the “reciprocal nature of a cruelty without end,” enigmatically represented in the film’s repetition of the Four Tops single “It’s The Same Old Song” on the soundtrack. Each jukebox spin of the record advances the plot while suggesting its characters can only move forward through endlessly backsliding into a greatest hits of their bad habits.

The Coen brothers’ simultaneous singularity and fascination with returning to the well of those golden age staples — not just songs but well-trodden genre conventions and old mythologies — is one of the many fruitful paradoxes Nayman returns to throughout his book. A book as playful and intellectually resourceful book as its subjects, The Coen Brothers is an appropriately exhaustive yet fun concordance written by a natural educator who has a knack for accounting for the work’s complexities as well its baser pleasures — like, say, the dream sequence in The Big Lebowski that is as silly as it is rigorous.

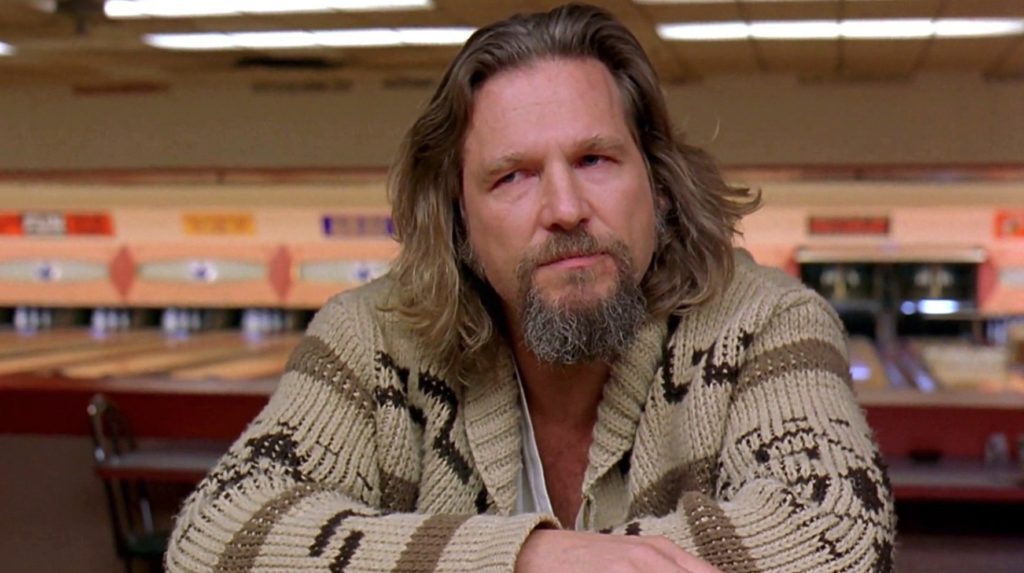

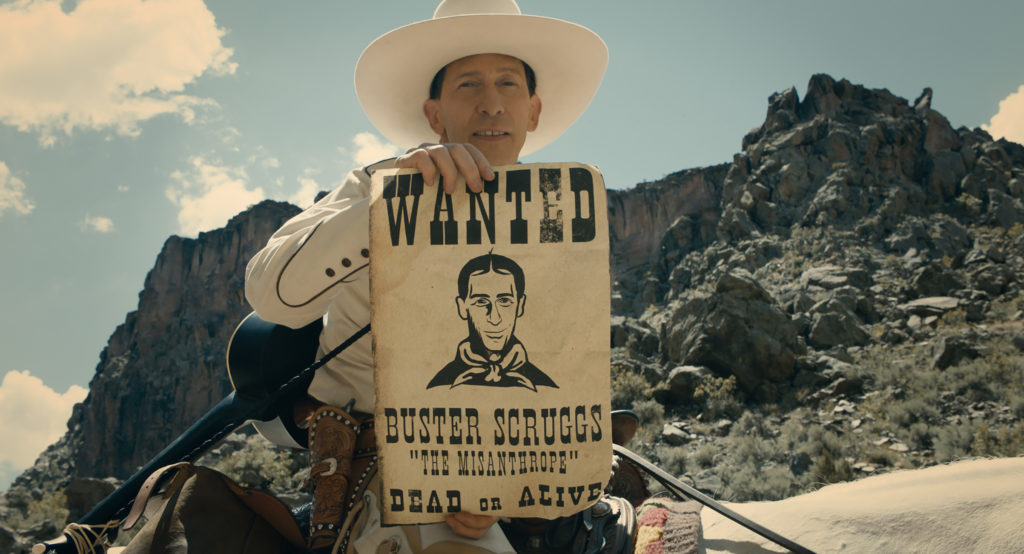

Angelo Muredda spoke to Nayman on the heels of the book’s release, and just ahead of the Toronto theatrical run of their newest, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. Our wide-ranging conversation spanned everything from the stoned genius and deep casualness of The Big Lebowski, to the Coens’ penchant for repeating themselves in novel ways, to their new anthology film — a brutal send up of the Western that Nayman, following Pauline Kael, suggests puts the sting back into death.

TFCA: You point out early in the book that objects serve for the Coens as doorways into the metaphysical while also being, well, objects. How do you see your own book as an object or a gateway to something, akin to the Mentaculus from A Serious Man — a probability map of the world?

Adam Nayman: There’s something to be said for collating and collecting and displaying the sheer beauty and invention and rigour of their filmic worlds. There’s the cliche that you wouldn’t mistake a frame of an auteur’s work for anyone else’s, and here you have hundreds and hundreds of frames that immediately tell you why these films are special. I worked with Little White Lies, which is a very visual film magazine, and they have a similar belief that you can use images to support prose, not to stand in for criticism or analysis. I see the writing as going very deep inside the movies, and if you move your eyes around the page, there’s the film. We chose images to support what I wrote, and we placed them at certain junctures in each of the chapters to drive the point home.

I also think the Coens are interested in ephemera, in weird little filing systems. A movie like The Hudsucker Proxy is so detail-oriented. In the original conception of the book, we saw it more like a farmer’s almanac or field guide to be cross-referenced. But it ended up taking a more fable-like, more poetic tone. If you notice, each of the illustrations for each of the chapters puts two elements of the movie into play with each other — having the cat cast a guitar shadow in Inside Llewyn Davis, for example, objects that activate each other.

You discuss in the book how the Coens are drawn to random mischance — but they also enjoy trying things together. Could you speak to the “deep casualness” you find in films as different as The Big Lebowski and Inside Llewyn Davis?

Those two films share the impression that things are happening in an erratic, discombobulated way, and the design and the motifs are not revealed at the end, The Usual Suspects style, as if there’s a twist. If you look at Inside Llewyn Davis, there’s something to how all the different amounts of money at every different juncture of his life add up to the same $200 — it gives the film a weird ledger-balancing board game quality, though they don’t go as far as making a Monopoly joke.

The Big Lebowski is the ultimate example. When critics reviewed it at the time, a lot of them found it borderline incoherent. They’re not wrong: that’s how it feels, and it does emanate from a stoned perspective. But every single thing in that movie connects. That dream sequence that he has is the illustration of that, where it’s not a random or incongruous hallucination. All of it, the bowling alley, the porn films, the castration anxiety, the modern art, even the checker-board floors in Lebowski’s mansion, are all suddenly put in concert with each other. That scene is in the middle of the Coens’ career and it’s the ultimate centrepiece of their career to date. They do so many things in that three minutes, and yet up top it’s just funny.

That tension is something you come back to a lot. Part of the appeal of these movies is their roominess, their ability to house all sorts of interpretations. What’s the draw for them, do you think, of making this room for interpretation while also connecting the dots? Is that a contradiction?

I think at this point it’s the way that their brains or their shared artistic brain is wired. They’re baggy and rigorous. They’re specific and spacious at the same time. When they employ genre structures, genre does a lot of the work in carrying you along and orienting you — giving you the proverbial thing that you paid for. In The Man Who Wasn’t There, you get the plot of a film noir. In True Grit, you get the nice forward momentum of the Western.

The films move horizontally, and then vertically — they plunge to depths, and the meanings hover above, in the realm of pretension. Your attention is carried forward by the plot but your viewing instincts and your intellectual response are moving up and down. It’s like in The Hudsucker Proxy: such a vertical movie. I love how the idea makes its way to the top of the building — a laborious process to get it into the top room — and then it’s the simplest idea in the world. Is it that the idea is profound and belongs on that top level, or does the idea become profound because it’s been raised to that height?

A related Coen contradiction that seems to fascinate you is their obsession with loops, even as they seem to care about what comes next.

I see it in thematic terms. One way to look at it, the petty way, is that their movies go in a circle and get nowhere. They’re so interested in continuity and the movement forward in terms of circles, and they seem to think that’s how human beings work. The Big Lebowski comes out and says it: “There’s a little Lebowski on the way.” His seed has found purchase, to quote Raising Arizona. There is something male about that, and something values-oriented. But that idea of the human comedy perpetuating itself — that’s the sweet way of looking at Lebowski. In No Country For Old Men it’s almost the same narration at the end — a cowboy describing a dream of fathers and sons, but there he’s quite concerned with death and his own finality. The end of Fargo is caught between those two poles. It’s wonderfully optimistic: two more months, we’ll have a kid. It’s also terrifying: two more months, we’ll have a kid. That’s the circle I find really compelling. As much as they retreat to the past, they always have an eye on the future.

The future keeps coming up. So much of Inside Llewyn Davis, for example, is about paternity and whether Llewyn can conceive of a future beyond flying cars and hotels on the moon.

It’s funny because a couple of scenes later he’s singing a song about an astronaut who doesn’t want to go out into space and push things forward — what could be more reactionary than that? In Hail, Caesar! they’re astonishingly open about this theme. The missile manufacturer says to Josh Brolin, “Hey man this is the future,” and the communist screenwriters sign their missives “the future.”

They have a number of films set in the past but they haven’t done a big sci-fi extravaganza yet, despite their interest in, say, 1950s visions of the future in The Man Who Wasn’t There.

Even The Hudsucker Proxy is all about the fantastical associations with the hula hoop. One of their under-discussed preoccupations is with fads. Not just there, but with the Soggy Bottom Boys in O Brother Where Art Thou, Inside Llewyn Davis and folk, dry cleaning in The Man Who Wasn’t There. Is there a more telling motif than the connection between O Brother and Llewyn? Llewyn says if it’s not new and it never gets old, then it’s a folk song. The Soggy Bottom Boys are playing “old-timey music,” but by the time the soundtrack comes out in 2000, that’s old timey-music even more so. In the world of the film, the song “Man of Constant Sorrow” becomes a hit, as it does in real life. It’s the same old song, which by the way is the song that plays throughout Blood Simple. In all these cases, songs are visualized as rotating records.

Some people would look at this motif and see it as self-soothing — why bother fixing things if everything is going to just loop back around to the start anyway?

For them I think the moral arc of the universe doesn’t bend toward justice, it bends toward neutral. There are a lot of different ways to look at that. You can look at it as conservative, as pragmatic, as existentialist, as Sisyphean. Very few of their films proffer a way out. In Llewyn Davis there is an escape hatch, but it’s not Llewyn’s to take — it’s Bob Dylan’s. One of the few people they seem to respect is true visionary artists but they tend to put those people at the edges of their movies, and rarely as their heroes. I don’t think they think Barton Fink’s a greater writer, but I think they think Bob Dylan’s pretty great. Like them he’s also a Jewish guy from Minnesota who’s endlessly gifted at reinvigorating and riffing on formulas.

You suggest that No Country For Old Men is a “study in how reverence does not preclude self-expression.” How do the Coens express a singular filmmaking voice given not just their reverence for other people’s work but their two-headedness?

We almost define them in terms of negative virtues: rigorous bordering on oppressive, contained, intellectual, coy, withholding, mysterious and somewhat sour. Even if you were a fan, and somebody threw those adjectives at you as a blind item, you’d say the Coens. I think No Country is an interesting case study in that there’s both more and less of them in it. It’s not really annotated. It’s not really a film nerd movie. It’s not an original story — it respects Cormac McCarthy’s story. And yet it’s so them because of the small, telling changes that make to it — turning the Carla Jean character into more of a figure of resistance, or downplaying some of the ugly conservatism of the Tommy Lee Jones character, or giving Chigurh his page boy haircut.

You talk a lot about recidivism in their films — characters going back to the well and re-offending, compulsively. There’s something of that recidivism in the way critics keep talking about their movies, endlessly looking at the new movie in the immediate context of the previous one.

The filmmaker that’s most like, I think, is Stanley Kubrick. No one should weep for Stanley Kubrick or the Coens — they’re over-exposed, over-analyzed, over-taught alpha male broteur types, they’ve been nominated for and won Oscars, and they’ve made a lot of money. But when you look at the reception of Kubrick’s work, it’s hilarious — Clockwork Orange is not as profound as 2001, then Barry Lyndon is too old-fashioned after Clockwork, and The Shining is too silly compared to the classicism of Barry Lyndon, and so on. Eyes Wide Shut took the longest to get the respect it deserved because nothing followed it to immediately redeem it.

I think the Coens have these three films — Blood Simple, Fargo, and No Country — that form these measuring sticks for the movies that come after, as well as the spine of their career. They’re movies audiences connect with or without a film degree, or to know anything about Dashiell Hammett, or Paul Bunyon, or Cormac McCarthy. Other ones, watching without context, may leave you feeling ground down, or like you didn’t get something.

It’s interesting that you can get lost about as easily in one of their more accessible texts though, not just something like A Serious Man.

It might seem like a strange one to pick for this, but No Country is the one I’ve liked more with distance. At first I thought it worked a little hard to justify its themes and put them in its characters’ mouths, but with time I’ve come to appreciate its gravitas. One of the reasons I love A Serious Man so much is how different it is from that. No Country is all about certainty — you can’t stop what’s coming, death will get you. In A Serious Man, every time people try and articulate something they end up with complete uncertainty.

Obviously you had to put the book out at some point. Would you have done anything differently if you had seen Buster Scruggs first?

It kills me that I couldn’t put it in there. Part of me wonders if I wouldn’t have found some way to start there. I like ending the book with Hail, Caesar! because that last pull up into the sky, the director credit, creates a good way to round off the question of their authorship. Their authorship is less obviously signalled in The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, which isn’t set in a movie studio, which isn’t all about directors. I’d have had a hard time not treating the new film with true finality, though, because it’s so much about death. As I’ve said, I think their films are often death-tinged, but it’s interesting how little the deaths matter in murder-heavy films like Blood Simple and Miller’s Crossing, where they’re adding up the plot. The deaths in something like True Grit, or Mikey’s missing-ness in Inside Llewyn Davis, they really register.

With Buster Scruggs, in a way they’ve never been so cavalier with violence and death. It’s filled with it, the way a wild west picaresque would be. As a movie about death — what it means to die, to not live anymore, to live with the weight of a loved one’s death or having caused somebody’s death — I can’t help but feel it’s on the path of maturity. Pauline Kael, when she wrote about Bonnie and Clyde, wrote that that movie puts the sting back into death. I think Buster Scruggs at times does that too, but very deceptively. Obviously they’re going to make more movies, but if this were to be it, when you watch the final segment and hear what the characters are talking about: pretty good. But of course, there’s always a little Lebowski on the way.

Words and interview by Angelo Muredda.