Reviews include Irena’s Vow, The Beast, and Before I Change My Mind.

Distasteful Representation in The Irishman

December 31, 2019

“The Irishman is a beat behind the social tempo of representation.”

It’s a Friday evening and I am walking into the TIFF Bell Lightbox to take in a screening of Martin Scorsese’s latest: The Irishman. Despite the film’s Netflix release, the theatre is a zoo. An usher — whose duties have morphed into that of a nightclub bouncer’s — attempts to file impatient patrons into a neat, snaking line leading up to the cinema. The queue, which extends two floors, is filled with all sorts of folks with a common goal: to surrender to Scorcese’s artistry for nothing short of three and a half hours.

There’s a lot to like about The Irishman. Scorsese did an excellent job at developing his main characters and exploring themes of love and devotion within Mafia networks. The film’s use of formal elements, particularly sound and editing, were also superbly executed. This is not surprising. For his many contributions to cinema, Scorsese is more or less a mythic figure. His status as a living legend is affirmed when walking through the Lightbox: stills from his work are plastered onto the walls in promotion of TIFF’s retrospective in his honour.

Despite all the hubbub, I felt frustrated after the screening. My discontent stemmed from a nagging question that rattled around in my head for the 210 minutes I lived with The Irishman: Why did Scorsese close off this story? Why was the film’s spectrum of representation so narrow?

The Irishman is a beat behind the social tempo of representation in the film industry. In several ways, the film positions itself as a tone-deaf relic of the past. While I can imagine Scorsese’s Baby Boomer audience finding great nostalgia in the work, it is incongruent with the increasingly diverse pictures that audiences are beginning to grow accustomed to. The film is true to its trailer: it offers spectators a layered crime narrative combined with an affected masculine epic of an aging muscled-up mob man. What the film failed to do, though, was to open its narrative paths to characters and stories that have been historically excluded from Scorsese’s high-brow pictures of American gang grit.

“The only sub-plot that includes women is actually used to demonstrate the bonds of brotherhood inherent in mob life.”

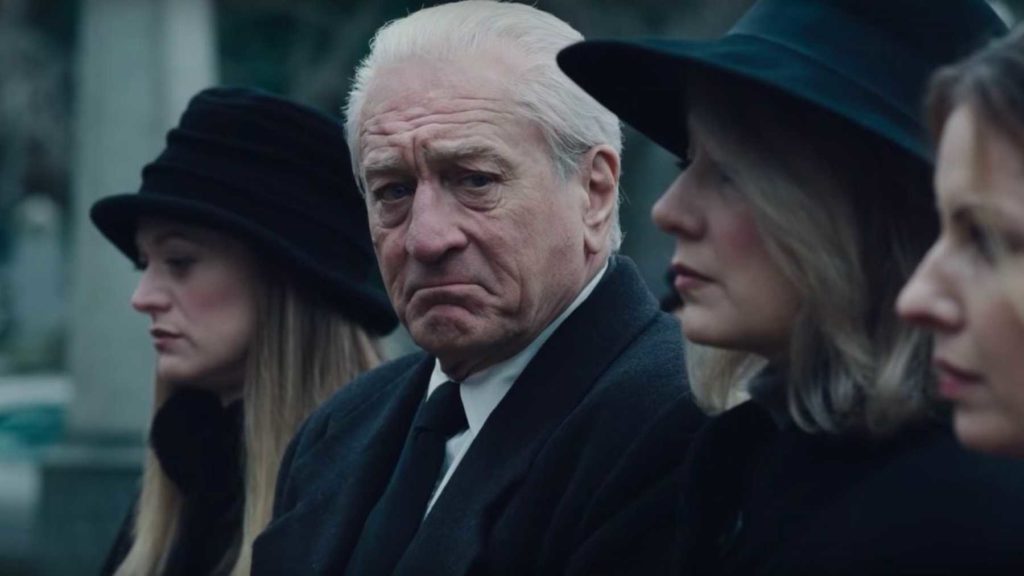

It may not come as surprise The Irishman does not pass the Bechdel Test. The film neglects to represent the interests of its women characters beyond a few superficial offerings. In The Irishman, women are carriers of emotion for others and pit stops along the narrative trajectory: they are sad, mad, in need of a cigarette, but are never meaningfully included in the progression of the story. Women are rendered as vehicles through which the film’s male characters may arrive at their own narrative terminals. We see this in Frank’s (Robert De Niro) relationship to his daughter Peggy (Anna Paquin). After arriving home from work, Frank is alerted that a local grocer pushed Peggy while she was shopping in his store. Instantly enraged, Frank drags Peggy back to the store and proceeds to beat up the grocer, stomping on his hand several times. This interaction strains Frank and Peggy’s relationship as Peggy grows fearful and suspicious of her father.

Despite the film’s continual return to Peggy and Frank, it exclusively uses their relationship as an instrument with which to understand Frank’s personal development and life choices. Whenever Peggy — or any of Frank’s daughters — are brought to the forefront of the narrative, it is to emphasize Frank’s increasing closeness to the mob and his gradual alienation from classic family networks. We see this time and again when Frank’s shady behaviour is met with disapproving glances from Peggy and her sisters.

Ironically, then, the only sub-plot that includes women is actually used to demonstrate the bonds of brotherhood inherent in mob life. This progression culminates at the end of the film as an elderly and isolated Frank attempts to contact his daughters without success. When The Irishman incorporates women into its story, they are ancillary to the plot and never an integral part of its development. This is by no means a narrative outlier in Hollywood and is painfully obvious in many of the director’s other films (including Goodfellas [1990] and The Departed [2006]).

The Irishman’s failure to broaden subjectivities to meaningfully include women is so disappointing because of its status as a work of national film art and a historical time capsule: a mirror held up to America throughout the 20th century. The Irishman is indulgent and smug in its several claims to authenticity. The film’s outrageous length seems to taunt its audience while simultaneously congratulating itself for every still, each implied to be too masterful to edit out. Its run-time matched with its narrative, which chronicles the life of real mobsters, positions the piece as an important historical picture. Further, the fact that the film was released nearly simultaneously in theatres and on Netflix — and doing extremely well on both fronts — is hard proof that people are buying into Scorsese’s artistry.

The Irishman’s position as a work of art, a reflection of American life that is received and accepted in such high volume, is what makes its exclusionary practices so distasteful. As a contemporary American epic and a reflection on society, the human condition, crime, and the shift of familial love, the film should logically make room for other voices. Unfortunately, however, instead of painting a well rounded, authentic picture of American society, The Irishman jettisons diversity to the margins. This omission speaks volumes: In Scorsese’s world, even with hours to kill, there is no room for people on the outskirts.

The film’s unwillingness to engage with women is so disappointing because it has so much potential to make new narratives seen. At a Scorsese screening, you feel like cinema is alive in the sappy, sentimental way your grandparents might describe their first movie. People are pushing their way through the line, itching to get a taste of the director’s mastery. His platform is enormous. Expert, intermediate, and novice film goers seem equally eager to see what is promised to be a more perfect rendering than the last, a work of art, a Scorsese. However, the auteur refuses to use his influence to do the most simple of tasks: To broaden the spectrum of representation to incorporate the diversity present within his audience. It is deeply unfortunate that even at the end of this decade, a mainstream film regarded as being “great” is so incredibly exclusionary.