Reviews include A Complete Unknown, The Brutalist, and Babygirl.

In Memoriam: Michael Cimino (1939—2016)

July 11, 2016

by Phil Brown

Once considered one of the great directors in an era when Hollywood actually empowered filmmakers, the late Michael Cimino spent the bulk of his career more notorious than successful. He died on July 2nd, 2016, at the age of 77.

Any mention of his 1978 Oscar-winning triumph The Deer Hunter is legally required to be followed swiftly by criticism of his industry-crushing follow up Heaven’s Gate, one of the movies most synonymous with the term “box-office bomb.” On one level it’s unfair to categorize it as such, but at the same time, the impact of that failure is a landmark moment of Hollywood history and a major part of Cimino’s legacy. Still, Michael Cimino is an fascinating filmmaker; one of those curious artists who beg film critics, scholars, and fans to ask what percentage of a career needs to be successful for a director to be revered.

Unlike most of his peers, Michael Cimino was not a movie-drunk cinephile for whom making films was the only passion he ever conceived. He studied architecture and worked in advertising for years before slipping into filmmaking through a back door. He began in the industry as a screenwriter, and the first film produced with his name on the script was a special one: Silent Running. An ambitious and complex science fiction picture that combines an unhinged Bruce Dern, a passionate environmental message, and some cutie-pie robots, the cult film is justifiably attributed mostly to director Douglas Trumbull. Admittedly, the effects-genius behind 2001: A Space Odyssey, Close Encounters Of The Third Kind, and Blade Runner made the film work on a budget no one else would dare have attempted, but Cimino’s clever script is what made it endure long after some of Trumbull’s remarkable illusions dated. From there, Cimino also co-wrote the distinctly average Dirty Harry sequel Magnum Force, worth mentioning only because through meeting Clint Eastwood on that picture, he became a director.

Cimino’s oft-forgotten directorial debut is the rather brilliant and strange buddy picture Thunderbolt And Lightfoot, which co-starred Clint Eastwood and a particularly Dude-esque Jeff Bridges as an unlikely duo of bank robbers. Filled with wonderful performances, striking visuals, and a deeply eccentric sense of humour that often slipped into the surreal, the little genre picture is an offbeat 70s gem worthy of rediscovery. It was enough of a hit to kick-start his career, and holds up rather well because of Cimino’s focus on character as much as action. The movie is also a tight and concise bit of entertainment, which is something that could never be said about another movie by the filmmaker and was likely a result of the notoriously conservative (in every possible sense) Eastwood’s presence on set. It was enough of a hit to give Cimino the clout he needed to make a passion project and the movie that he should be remembered for.

The Deer Hunter is flawed, but a masterpiece that’s too often graded on a curve because of what followed. It’s one of the most visually stunning films of its era, with an opening act that’s Altman-esque in its dedication to as an egalitarian character study. The second act features some of the most heart-poundingly intense war footage ever staged, while the third transforms the early naturalism into a fable and somehow succeeds. Sure, the film is a bit bloated and takes liberties with reality, yet somehow it all congeals into a potent portrait of America’s sick obsession with violence and war that’s aged rather well. The Deer Hunter was a commercial, critical, and award-winning success that any filmmaker would be proud to have on their resume. But then…

Sadly, it’s his follow-up film, Heaven’s Gate, that hung around Cimino’s neck like a noose for the rest of his career. A revisionist Western with dark implications about that iconic era of Americana, the film spiralled out of control during production with costs mounting so high that it essentially bankrupted United Artists upon release. And at over three-and-a-half hours long, it’s a tough sit.

The critics were harsh enough to hasten the film’s demise. Since then, the movie has been reappraised, even enshrined in The Criterion Collection, and it is actually a rather intelligent and beautifully mounted film. The problem is merely (if you can call it that) excess in every aspect of production, as Cimino’s unchecked ego created an undeniably overblown vision. Still, it’s hardly a bad film, just one trying so hard to be great that it can’t help but fall short during a punishingly-long running time. It should have been an out-of-control epic that Cimino could bounce back from when his ego subsided, but unfortunately the box office failure was so substantial that he never really got a chance.

Michael Cimino made four more films in the 16 years following Heaven’s Gate and they were increasingly worse. Take 1985’s The Year Of The Dragon, which took five years to produce and aside from some wooden performances and questionable politics, is actually not bad. It was a return to the stability of genre pictures, a gritty detective story with a strong n’ troubled performance from Mickey Rourke, and some genuinely great action scenes. And yet—it didn’t do well at the box office.

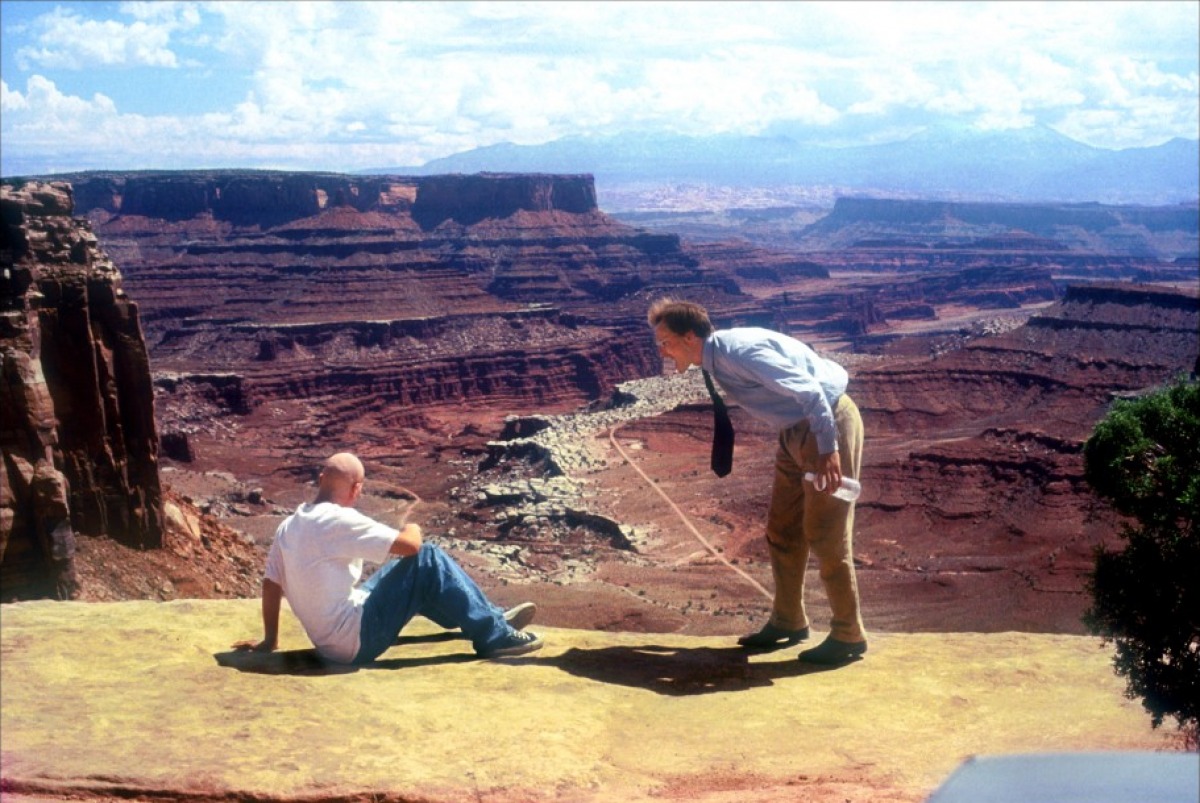

From there, Ciminio chased whatever project he was allowed to make with increasingly frustrating results. The Sicilian was a pretty pitiful Godfather knock off, Desperate Hours was a desperate re-make, and it’s hard to tell what Cimino’s final failure The Sunchaser was even supposed to be. Yet, as tough as it is to watch those three passionless works-for-hire, Cimino’s keen eye for cinematic spectacle and knack for drawing out eccentric performances still pop up occasionally, taunting viewers with a talent that was never allowed to flourish outside the bubble of New Hollywood. It’s also probably not a coincidence that none of Cimino’s late career failures featured his name on the screenplay—that was the talent that kicked off his career in the first place!

Michael Cimino had a less-than-spotless track record. But what of it? The two films he wrote and three that he wrote/directed from 1972-1980 have all aged remarkably well, and show a quirky talent with undeniable vision. That should be enough for him to be remembered as a genuine filmmaking talent and not merely a cautionary tale. Especially since so many of his contemporaries never managed to succeed outside that fabled decade, either: directors like Peter Bogdanovich, Hal Ashby, Michael Ritchie, Richard Rush—hell, even Frances Ford Coppola—remain beloved filmmakers despite their 1980s expiration date. The same should be true of Cimino, but unfortunately he made the movie that ended the party for everyone. He also somehow managed to seem stranger and more egotistical in every public appearance that he made after the ’70s, so the gossip ultimately outweighed the good in his career. There’s something rather tragic about that.

The odds of Michael Cimino ever making a movie again fell somewhere between slim and none at the time of his death, so in 2016, he was all too easy to dismiss. However, that feels like a mistake. Cimino was a truly gifted filmmaker with an undeniable vision (even those who despise all his work must admit the latter). If we’re lucky, his legacy will be more than a footnote to Heaven’s Gate’s permanent shift in Hollywood production. There is a terribly sad arc to the Michael Cimino story that—although self-imposed—deserves sympathy in his passing.