Reviews include Irena’s Vow, The Beast, and Before I Change My Mind.

The Conversation of Cinema: Champions and Critics

June 11, 2015

by Jason Gorber

At this year’s Cannes Film Festival Jury press conference, I asked those assembled on the dais how they felt now that essentially they were acting as film critics. “I don’t know that we are,” Jury co-president Joel Coen responded, “we’re here to reach a consensus on which of the films we see here are amongst the best.”

Coen added that “establishing what the best film is” among those in competition is “sort of anathema to artists, especially when we have to pronounce on our own art form.” For him the notion of being a critic is to be critical in the negative sense. “Part of what was discussed in general is we’re not exactly critics here”, he argued, “it’s not about ‘we hate this’, it’s not about what somebody did that we can’t stand.” Instead, “it’s about what films we really like and want to celebrate.”

As both a critic and sometimes-jury member, I both understood where the filmmaker was coming from, and also believe that in part he may not fully appreciate the scope of what we do (when asked about his own relationship to his critics, Joel quipped that “that’s a subject I’d rather personally not get into”).

Coen’s distancing himself from the world of film criticism is hardly surprising, given that what falls broadly under this rubric rides the gamut from parochial academic proselytising to out-and-out appendages of studio marketing departments. The maxim has never been more true that “everyone’s a critic”, particularly when one need only look to an Amazon product review or Letterboxd list to find all and sundry publishing their adjudications of various works.

So is Joel then correct in saying he’s not a film critic per-se when he’s president of a Jury? Given that deliberations are behind closed doors rather than on the page, in some ways the Coens and their fellow jurors have an advantage over most who have to defend their point of view in the body of a review. The jury declares a winner in a given category with a few choice and positive adjectives and lets that stand. In that way, some would argue, awarding the Palme d’Or is the ultimate capsule review – pithy, provocative, yet definitive.

One of the things that Coen’s description of the group as non-critics misses out on is the very function that in fact describes many of us to a T. At festivals in particular our most vital role is to do that very championing he refers to. Standing in line, we debate with our colleagues, telling anyone interested (including, it should be noted, festival programmers and buyers) about a particular title that moved us. Numerous times at the likes of Sundance and Cannes (where the sense of discovery seems more acute than at a festival like TIFF) we play a role in helping a smaller film get noticed from the larger selections, resulting occasionally in bidding wars, follow-on articles from the trades, and so on.

This sense of celebration is sometimes misunderstood by certain members of the critical community who feel this is nothing more than “cheerleading.” They instead mandate that critics offer a more reserved take on films well after a certain initial reaction has been allowed to settle, and often revel in presenting contrarian points of view in order to distinguish themselves in the fray. And to be sure, there are those who laud everything they see in equal measure with no sense of either critical acumen or attenuation of enthusiasm.

For most that do this gig, however, a proper and vital role of film criticism is this sense of “championing” a great work. If we’re able to find a selection with a festival programme that moves us, a movie that stands above the rest and is thus well worth celebrating, then many of us are not shy to use whatever means we have to trumpet this fact. While achieving a consensus on what should be championed is certainly unlikely, yet out of this cacophony of voices certain titles tend to be the ones that become the focus of discourse.

This leads to another central question about the role of the critic – Who are we to believe when a film is lauded? Is it simply the film that’s championed the loudest by the biggest publications that’s the one that’s sure to gain traction? This isn’t always the case, and even less so due to the explosion of critical voices and demolition of some of the old guard.

I wrote a graduate thesis that explored these issues, examining the philosophical foundations underpinning critical discourse. Building upon the work of Noel Carol and David Bordwell, my argument broadly concerned the shaky epistemological underpinning of criticism – Namely, if there’s no underlying “truth” but simply opinion that forms our critical reception, how does one wade through to find out what to appreciate without a touchstone as handy as an awarded jury prize?

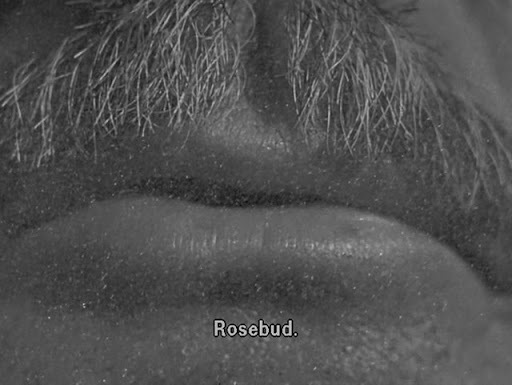

In making their arguments, the “facts” that critics draw upon are “cues,” elements of plot, character, setting or action that can be objectively articulated and agreed upon by all involved. We can all agree that in Citizen Kane the term “Rosebud” is a clear cue that can be called upon when discussing the film’s merits, but one can debate critically whether it’s relevant to the appreciation of the story that it’s a metaphor for childhood, the marking on a sled, or a metatextual fact such as the rumoured name for the clitoris of William Randolf Hearst’s mistress.

We as critics are not in the business of uncovering epistemologically rigorous “truth” – the goal, in other words, is to be convincing rather than to be “right” in a strong, capital-T truth sense. If we can elegantly contextualize these cues while providing a rhetorically strong and compelling argument about the given merits of a work then it’s a success. Whether we’re right or wrong, in the sense of ontological truth, is outside the frame of the critic’s project.

This leads to a conundrum – if all we have is debate and rhetoric, how then do we shape this discourse in any meaningful way? In my thesis, I suggested that if all we had was this dialogue, what I called the “conversation of cinema”, then participants who were anti-discursive could be, frankly, ignored. If someone’s goal was to stop the conversation, they were counter-productive to the whole game. We’re collectively having a chat, and someone yelling loudly that they have the answer, and the only answer, should simply be ignored.

I’ve found over the last two decades of writing about film that the implications for this are profound. My job, such as it is, is to lob an opinion out there into the conversation of cinema in the hopes that there’s someone out there that will respond.

This is easier to do when it comes to regular releases, where the audience is already predisposed to seeing a given blockbuster or regular multiplex release and thus participate in the conversation. This becomes harder with the smaller festival films that play sporadically throughout a run, often for years, to relatively local audiences.

It’s here that the role of the critic and jury member merge, contrary to Coen’s assertion, and where that very sense of discovery and celebration is absolutely vital to both how we respond and the life of that film in terms of its place in the conversation. What sets one work apart from another often relies upon these discoveries that we as critics (and programmers and jury members) make, that needle in a haystack moment of excellence that can result in a small, independent film being elevated to a wider profile.

In other words, we celebrate a given work so that we can have more people talking about it. We, at our best, are fostering participation in this larger conversation.

Even this celebration by critic and jury member alike can backfire. This year’s Palme d’Or winner Dheepan already has several participants in the conversation shaking their heads, quick to dismiss the result and shape future audience consumption of the work. Audiences will be presented the film as a winner of a relatively arbitrary competition (a selection of seventeen films that were in competition, as opposed to the many in alternate competitions or simply out-of-contention), and a film like Dheepan, regardless of its merits championed by some, may not live up to these heightened expectations.

Juries can walk away from the conversation, having already made their definitive stand, while we as critics are still in the trenches, continuing to write about given works as they travel through the festival circuit, into wider release, and then ultimately to the end-of-year awards season.

So while adjudicating art may be anathema to artists, as per Joel’s point, as critics and jury members alike it’s the core of what we do. The goal, however, isn’t to simply proclaim a film’s worth and be done with it, but to try and help shape the conversation one way or another, and in turn to give a richer experience of the work long after the curtain has closed. Even the most famous of film’s dialectical devices, Siskel and Ebert’s thumbs up or down, had behind it convincing (and at times complex) articulations about the work in question.

As per concerns regarding the anti-discursive or “totalizing” criticisms, those works that try to state things definitively without allowing space for further participants in the conversation, these forms of championing (or dismissing) films can be justifiably ignored. A critic who cannot see the art in a gory genre film is just as counterproductive as a populist who refuses to take a chance on something experimental or new. A more sensible and common approach is to champion a film when deserving, and do so in a way that leaves room for the reader to have their own response, even if that response is in direct opposition to our own. It’s the difference between thinking we as film critics are declaring the worth of a work, or presenting an argument about what we believe its worth to be, recognizing the role we play within a greater conversation.

This doesn’t make criticism weaker or milquetoast in its convictions, but instead more fully shapes just what we do when we’re at our best. We can draw upon film history, we can make allusions to other works, we can employ any number of such rhetorical ploys to demonstrate clearly and coherently just why we think a given work is worth your attention. This is especially true when it’s not already obvious, be it a quiet social drama set in some East Asian village, or a blockbuster action film that rises above the usual tripe and gives us something genuinely new and thrilling.

What’s most exciting about what we do is that continuing sense of discovery. The longer we write about films the harder it is to be truly surprised, of course, but when it does happen it’s no less energizing, and enthusiasm comes easily. You hope for one or two experiences like this when marathoning through dozens of films through a festival, and when the goosebumps pop up on your arms, I strongly believe that’s cause for us as critics to play a central role in getting the word out early and often.

During the closing press conference, Joel Coen changed his tune slightly. “This experience does change your perspective as a movie watcher”, he said, as “having to see this many movies this intently, and then discussing them with a group, profoundly changes your perspective as an audience member in a very positive way.” Xavier Dolan, who is often quite deprecating about his own historical film knowledge, admitted that he hadn’t previously “discussed movies with such depth, generosity and emotion. We discussed the movies extensively.” He also admitted that “as filmmakers we often think that no-one will notice” a given element or cue, but added “Nothing goes unnoticed!”

It’s those of us that have gone through this profound evolution that have the audacity to say that, hey, we’ve got something to contribute here to this discussion, listen to us. For those of us with a dash of humility and skill, some rhetorical flair and ability to tease out the cues and make our arguments fruitful and enjoyable, then we’ve done our job as critics.

A critic’s most rewarding moments are when we find a film that’s worth championing, not when we take one down a peg. It’s where we can marshal all of these elements to encourage our readers, our own little audience, to take a shot on something they otherwise would not have seen. At the least, we may argue convincingly it’s a film to take in to form your own opinion about, and hopefully you’ll find the experience as rewarding as we have.

Criticism is not, as Coen suggested, merely a matter of decrying a work and picking it apart. When we do champion something, we, like the members of the Jury, do so in order to help move the conversation forward.

And it’s a conversation worth having, whether you agree or not with what we present as our contribution.