Reviews include Superman, Apocalypse in the Tropics, and To a Land Unknown.

White Lie Directors Calvin Thomas and Yonah Lewis on Collaboration and CanCon

February 24, 2021

By Jason Gorber

Calvin Thomas and Yonah Lewis have carved out a unique slice of the Canadian cinematic landscape over the past decade. Their first feature was 2011’s micro-budget coming-of-age feature Amy George, followed by 2013’s The Oxbow Cure. (The latter was described as “deeply strange and instantly captivating.”) Then came Spice It Up, their 2018 paean to Toronto’s DIY cinephile scene. Their latest film, White Lie, is a sophisticated yet eminently watchable film that borrows from both the European art scene and Hollywood’s most salacious thrillers.

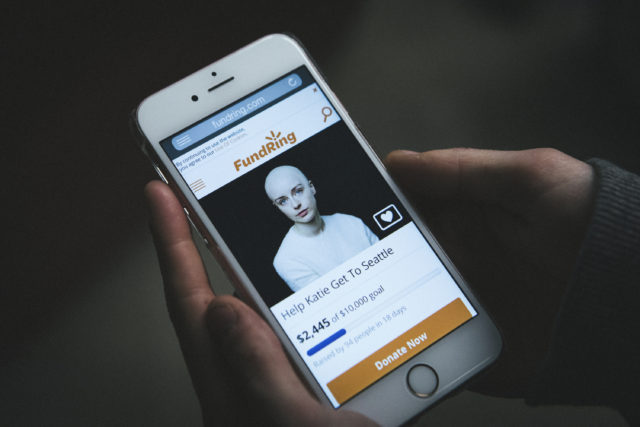

With a stellar lead turn by Kacey Rohl (Hannibal, Arrow), White Lie tells the story of Katie, a university student who uses her social media followers to solicit donations towards her cancer treatment. As the title implies, this is all a scam. As Katie’s lies unravel, White Lie assumes more depth and urgency. The unique and provocative film received near universal praise upon premiering at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2019. White Lies was named to TIFF’s Canada’s Top Ten list that year, won attention from other major festivals, and earned four nominations at the Canadian Screen Awards.

Now in 2021, White Lie is a nominee for the Rogers Best Canadian Film Award from the Toronto Film Critics Association. We chatted with Thomas and Lewis as they prepared for their next project, discussed several reference points for the challenging character study, and how the events of the last year reshaped perceptions of White Lie.

How did the idea for a character study wrapped in a psychological thriller came about?

Calvin Thomas: I’d read an article about someone doing something similar in Canada. They were doing it as severely as the character in our film, transforming herself, transforming her body, and telling lies in person. We flagged that and thought it was a great character. We were working on different things at the time and filed it away, yet every couple of months when we had a moment to talk about future projects, we’d come back to it and see if we could explore it. It took years to get to the point where the film is today.

Yonah Lewis: I don’t think we knew at the beginning that it was a thriller. It started as far more of a character piece, asking who the hell does this kind of thing? There was some gestation, some deliberation, and a lot of talking about it before we realized we had the ability to crank it up so that it’s not just this depressing, harrowing story. We always treated it like a chamber piece, and I think, to some degree, it is. It’s not that everyone’s stuck in one space, but it’s usually [Katie] and one other person dealing with whatever her lie is in that moment. It took us a while to figure out how to make that as exciting as possible. The first idea was that she had already been found out and she was going from person to person who had donated money to her and attempting to apologize with hopes that there would be no real consequences or ramifications. That sounded like a version of torture porn.

Before I saw White Lie, I heard people alluding to the Dardennes. I admit that I hate the narrative of films like their Two Days, One Night, where she goes door to door begging. I’ve described it as the worst version of the TV show Survivor ever! I also don’t love Romanian slow cinema and its claustrophobic misery. Both of these examples were used by critics when describing your film, yet I saw echoes of Vertigo or other films that are unafraid to have plot and still be psychologically complex.

YL: You mention Romanian New Wave and the Dardennes, and they definitely were keys to tell this story. What they do very well, which is also a very Hollywood thing, is to provide obstacle after obstacle after obstacle. Whether it’s those guys or it’s Robert Zemeckis with Back to the Future, obstacles are fun. Our “apology version” didn’t really have that structure–you were just repeating the same thing. We had to find in each of the scenes something new. It got to a point where we realized there was a procedural thriller aspect to it, but I don’t think that was at the forefront in the way that it became so eventually. At some point, we realized that when people were reading the script, it was becoming a bit of a page-turner.

CT: That spirit was inherent in the script. A lot of the feedback was people saying they couldn’t put it down. We typically write quite clean without a lot of description. It’s very dialogue-heavy, so you can get through our scripts without being bogged down by descriptions of what the character’s feeling. People just inherently wanted to see what would happen next, and that translated to the film quite easily. From a directing standpoint, we don’t do a lot cinematically to make you feel something. There aren’t a lot of “mood moments” with Kacey just sitting there, with a slow camera pushing in or a zoom to create psychological anxiety. The film just doesn’t stop. While editing it, we got away from any heavy-handedness. You’re hopefully on the edge of your seat, feeling the suffocation.

Did it help that there was a true story to have as a point of reference, in order to avoid criticism that you’re men who are portraying a woman in a negative light?

YL: That was very tricky from the beginning. We got a lot of feedback from people suggesting this woman is so awful, she’s despicable, and that nobody’s going to like this. Our response was always that there are 800 million movies we all love that are about horrible men. There should be some movies about women who aren’t great! There’s the occasional Gone Girl, but those people are usually villains. We didn’t want Katie to be a villain because you’re stuck with her. We knew that she was doing something awful and reprehensible, but because we were putting you in her shoes for the entire film, you had to identify with her. As everybody says, most of directing is just casting, and finding someone to play Katie was our main job. The entire thing rested on her shoulders.

But I’d like to think it’s not an anti-#MeToo movie. Quite a few people are doing this, and it’s a bit of a phenomenon. With the rise of Internet and social media, you can hide behind your computer more. We noticed in our research that we tend to find more women doing this than men—men have found their own ways to do horrible things. At the end of the day, there is a very practical reason why the central character was a woman. For someone with a shaved head, when it’s a woman, it’s much more visually striking than when it’s a man. You see a lot of bald, but you don’t see a lot of bald women.

The original title for White Lie was Baldie, was it not?

YL: Originally, it was called Baldie. Our sales agent started pitching it to a bunch of men at Cannes and everybody there was this old white bald guy and didn’t love the title, so we came up with something else.

White Lie can obviously be read multiple ways. The title evokes a lie told for good reasons, but it also has a racial connotation about a person who can get away with stuff that others cannot.

YL: We shot White Lie in 2018. The way in which cinema is read through a racial lens has become more present since this movie was released. There’s an interesting reading into why this white woman is going around and is believed very easily, and essentially tramples a whole bunch of people of colour throughout. The film takes place in Hamilton, but when we wrote it, it took place in Toronto. We moved to Hamilton for tax credit reasons! We were just trying to make it feel accurate to what we saw every day outside our door in Toronto, which is wildly diverse. Katie goes to a Black doctor to get her medical records two thirds of the way through the film. That was originally written as a man, but we didn’t have anybody particular in mind. We saw a bunch of tapes and the person we found most interesting ended up being a Black actor. There were other characters who were written with particular ethnicities in mind for various backstory reasons, but through the confluence of events, some script things, and some aspects of the way the world works, at least in Toronto, it ended up being a very diverse cast and this very white woman in the foreground.

How did you settle on your key performers? Were you just watching Hannibal and thought Kacey Rohl would work?

CT: We were watching a lot of TV! Our casting agent would send us names of people that they thought would be a good fit for the role. Kacey auditioned. She sent a tape, and I always joke that it looked like The Blair Witch Project, where she’s snotting. She had long hair at the time so she wore a toque. It was low quality video and she’s very close to the frame. She did a very emotional read of the lines that we sent her. It was too much.

She was full on snot-crying? Are we talking Jennifer Hudson in Cats level of sinus acting?

CT: Yeah, it was gnarly, but it caught our eye. Sometimes you get very numb in casting. We probably saw over 100 people for that role and it just blurred, especially if people weren’t taking chances. Kacey approached it from a different angle and we were electrified by her performance. We had a call with her and said what she did was really interesting but we wanted her to try something else. We wanted to test her range. She sent us another tape and it was in completely the other direction. It also wasn’t necessarily right, but it showed that she could take a note. There wasn’t really anyone else in the running for that part once we had seen her second tape.

This film was made back in 2018, which feels like a totally different world after COVID, the BLM protests, etc. How has the film changed for you guys?

YL: Once you lock a film, it’s rare that you go back to it except for maybe the first time it plays at a festival. Movies take on their own lives almost immediately in your mind. They start becoming both better and worse than they actually are. Once in a blue moon, when we go back and watch a section of any of our movies that we haven’t seen in five years, we’re both impressed and not impressed with some things. It does feel like it’s from a long time ago, but the film we made before it, Spice It Up, started shooting in 2013 and didn’t release until 2018. So, for better or worse, we are used to films having a very long gestation process. Nobody is a greater critic of their own film than Calvin and myself, but there’s a lot that we cracked in this one that we hadn’t in our previous, smaller, micro-budget films. To get on this call with you, we stopped writing the new script we’re writing. So much of the new one is influenced by what we think we did well on this one.

How does your collaboration work?

CT: It works very organically. We’ve been working together for 15 years, so by now it’s a very well-oiled machine. Our composer and editor, Lev, who is Yonah’s brother, is a third member to our team. He is very collaborative with the script, casting—every part of it. Oftentimes we equate it to the way a band works. Having two heads that are on the same page on set can be valuable because one person can go to the camera department and one person can go to the actors. This is the first time we had a monitor on a shoot, because we usually operated our own films and shot our own films. We could stay at the monitor, see what’s not working, and mutter while the take’s happening.

When we’re writing, we usually outline collaboratively. There’s a lot of discussion, and just throwing things out. We spend a lot of time dealing with structure. I’ll do a first pass of the outline, and Yonah works behind me. He’s usually about 10-15 pages behind me working much slower than I am. I try to bang out as many pages as I can, 5-10 pages a day, and Yonah’s trying to drive the train behind me and make sure we’re going straight. It’s worked quite well in the last couple of years in terms of being proactive. I know that my back is covered because Yonah’s fixing my spelling mistakes, making my sentences sound good, and spending more time thinking about things. Meanwhile, he knows that he has more than just a blank page ahead of him.

Were you surprised about any of the responses to the film?

YL: In general, we’ve had a very good response. We’ve made a lot of micro-budget films that some people like and some people don’t. But there are always creative challenges when you’re making films for $2500. This film had a small budget, but a “real” budget. We had a real team. It wasn’t just Calvin and a couple other friends making movies. One of the things that has been echoed back to us is that people were rooting for [Katie] to win. We wanted audiences to want her to get away with it, and then take a step back and remember she’s doing something horrible.

We were obviously concerned about being two white male filmmakers directing a movie about lesbians. We got some great response around the relationship between Katie and Jennifer in that it’s just normalized. It’s just a relationship in a movie, and that’s what we were going for in the film. The biggest note we got from audiences is about the lack of closure. From our point of view, we’re clearly telling you what’s happening at the end: that she’s going to keep trying this until she can’t, and thus loses the person she’s doing it for.

Spoiler: It’s not a happy ending.

YL: It left a lot of people wanting some semblance of “more.” If you go through the IMDb or Letterboxed reviews, some people say that they loved the ending and other people say they hated it. We put people through such a harrowing ordeal and they were with us all the way, and I think they wanted some sense of closure that we didn’t give them. At the end of the day Calvin and I made the movie we wanted, and I think we feel very good about it. Yet I wish there was some way we could have given people what they wanted while also making [the ending] the moment that we wanted.

Was there a more overtly cathartic cut?

YL: Early drafts of it had scenes with her in court at the end.

CT: I just watched White Squall last weekend, the 1996 Ridley Scott film about being on a boat with Jeff Bridges. That movie has a climax and an 18-minute court scene at the end. I hated it so much. As true as what Yonah’s saying is, I’m not sure that would have been the right approach.

You mentioned Gone Girl – did you draw upon some of the schlocky ’90s stuff, like Sleeping with the Enemy, for some of this tone?

YL: We did spent a lot of time looking at that type of ’90s thriller cinema. We are huge fans of Adrian Lyne’s work and he was a big directorial influence on the film. We were always balancing between the Dardennes/Romanian international art house world and the Hollywood thriller/Adrian Lyne thing. The movie in our minds started as a procedural and turned into a psychological chamber piece. For us, the tension was that it transformed structurally from one thing to the other.

What does it mean to you to be recognized as one of the TFCA’s top three Canadian films of this year? What does film criticism mean for you in general?

CT: It’s obviously a thrill. The films that we’re nominated with [Anne at 13,000 ft and And the Birds Rained Down] are exceptional. It feels nice to be a part of a cohort of filmmakers who I think are doing incredibly interesting work within Canada—work that’s leaving the country but also being embraced and celebrated in the country. As a younger filmmaker, and having talked to colleagues, that is something we’ve been wanting for a while. It’s nice to see that consistent output being celebrated. To be a part of that and to be honored in that way is a treat. Some of our movies have been able to be seen because of local criticism. Obviously, the spots for and the spaces for criticism are getting smaller, not just locally but around the world, so it’s harder to get people to pay attention to our work.

YL: As Canadian filmmakers, we’re always grappling with being embraced in the country while also wanting to be embraced outside of the country. A lot of the time, a movie isn’t seen as being successful until the international scene cares about it. That’s a problem. These moments where we can celebrate ourselves are important. Canadian cinema needs to be better so that Canadians can care about it. I think it’s a cycle. It’s harder to make good movies if you don’t have much of an audience for them, and there’s not much of an audience if you’re making bad movies. There has been a history of that in this country for a long time. I can’t say that our movie or any of our colleagues’ movies are completely fixing that, but we’re certainly trying to make movies that people care about elsewhere and here. Hopefully we can continue doing that for a while!

Make good movie. People see movie. Movie does well. Canada does well.

YL: Exactly, you got it. Word for word! [laughs]

White Lie is available to stream on Crave, Hoopla, iTunes, Vimeo, and Google Play.

Tune into the virtual TFCA Awards Gala on March 9 to see who wins the Rogers Best Canadian Film Award.