Reviews include Irena’s Vow, The Beast, and Before I Change My Mind.

Fires Were Started at TIFF 2018

September 24, 2018

What are you going to do when the world’s on fire?

There’s this scene in Gloria Bell — Sebastián Lelio’s American remake of his own 2013 Chilean film Gloria, which had its world premiere at this year’s Toronto International Film Festival — where a handful of middle-aged friends converse about the end of the world. Someone says every generation thinks theirs will be the last. Someone else responds by saying, “And one of them will be right.” Gloria Bell is, for the record, not a sign of the apocalypse; in fact, despite its seemingly cynical genesis and nearly shot-by-shot fidelity to the original, it’s quite wonderful, with Julianne Moore offering a compellingly distinctive variation on Paulina García’s sublime performance and John Turturro actually rendering the titular heroine’s boyfriend with greater sympathy and complexity than his predecessor, Sergio Hendández. All of which is to say that Lelio is in the unique position of having his best two films be the same film. But here’s where I’m actually going with all this: the world is burning, or drowning, or asphyxiating, and even charming character studies set in comfortable milieux cannot help but comment on it, never mind the abundance of TIFF selections devoted to chronicling our bleak times, end times or quasi-end times.

In Olivier Assayas’ Non-fiction, the publishing industry becomes the focal point for a larger discussion about the digital age dark age and art and culture in retreat, while Brady Corbet’s Vox Lux chronicles the life of a pop singer as a means of addressing, well, everything, from mass shootings to terrorism to the end of privacy. Echoing in its way both Demonlover and Summer Hours, the former is a relatively subdued effort by Assayas’ standards, yet it succeeds as a smart, chatty meditation of the elusiveness of wisdom in a time of vertiginous upheaval; the latter, meanwhile, is wildly, admirably ambitious, as though Corbet is striving to cinematize Don DeLillo, but eventually falls on its face due to an overburdened thematic and an overwrought performance.

Still, in its attempt to address cultural crisis, Vox Lux doesn’t sustain quite the level of injuries as American Dharma, Errol Morris’ feature-length interview with Steve Bannon, which finally has no reason to exist. In one scene Bannon at once flatters and mortifies Morris by claiming The Fog of War made him want to be a filmmaker, which perhaps goes to show just how easily an artist’s intentions can be misconstrued. American Dharma cannot possess a fraction of The Fog of War’s relevance because, unlike Robert McNamara, who by 2003 was quite elderly and eager to get things of his chest, Bannon has no inclination to utter a word that doesn’t adhere to already firmly established and heavily documented populist bullshit. What’s more, Morris’ sense of irony turns on itself as his use of location, slow motion and Paul Leonard-Morgan’s leaden score merely provide Bannon with a faux-valiant framing that could easily be seen as simply valiant. I have no doubt Bannon is pleased.

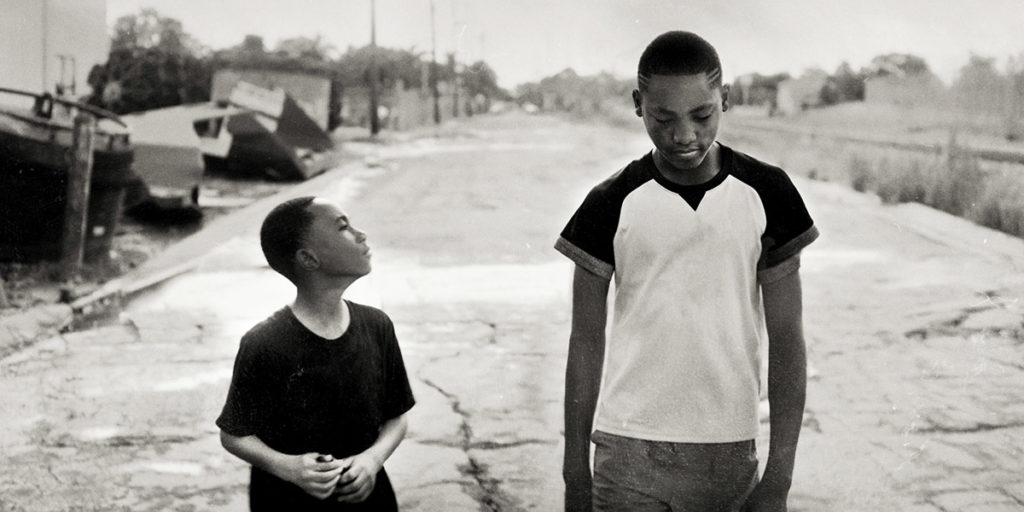

Perhaps it takes an outsider to truly see what’s stewing in the shadowy heart of the United States — an outsider prepared to surrender his narrative to his subjects, and to select subjects that, unlike Bannon, are the truly marginalized majority in desperate need of a platform. Easily one of the most vital, urgent films of the year, What You Gonna Do When the World’s On Fire? is the latest from Italian-born, US-based Roberto Minervini, whose modus operandi is to embed himself in communities and very slowly, carefully sculpt a portrait of the people he meets there. His previous film, 2015’s The Other Side, concerned a community of largely disenfranchised white people in Louisiana seeking to bolster their sense of identity through the forming of armed militias. Time has rendered it the most meaningful and prescient document of the immediate pre-Trump era. Photographed in gorgeous black and white, What You Gonna Do is the other side of The Other Side, chronicling the lives of a number of black Louisiana residents struggling to seek justice in the wake of so many killings of black men, and to find dignity in a social structure still contaminated with institutionalized racism. It features complex, memorable characters young and old, demonstrations from the New Black Panther party, and much making of music — one of many signs of power and vivacity amongst people who would have every reason to succumb to despair.

The world is already on fire in Anthropocene: The Human Epoch, from the directorial trio of Jennifer Baichwal, Edward Burtynsky and Nicholas de Pencier, who collaborated previously on Manufactured Landscapes and Watermark. Brimming with simultaneously gorgeous and horrific images gleaned from sites of environmental devastation the world over, the film is a survey of activities that testify to the titular theory that we are now living in an epoch in which mankind has altered the world’s geography and ecosystems to an extent that is fundamentally transformative and irreversible. In Kenya, Russia, Germany, China and Chile, in Florida and British Columbia, in open mining pits, factories, tunnels and warming seas, Baichwal and company gather perspective. What makes this so much more vital than a typical activist documentary is that the filmmakers go places with the understanding that it is incumbent upon them to return with something more than what they came for, to infuse their film with discoveries, not merely with evidence to build a case. It all works best when the filmmakers linger long enough in their locations — a landfill, say, or a lithium cultivation pond — that we’re able to register scale and consequence, to truly see something, to understand it, rather than simply be told. Which is probably why I found Alicia Vikander’s intermittent voice-over narration to be Anthropocene’s weakest element. The facts, numbers and dates provided via Vikander’s cool, even intonation feel didactic and easy to tune out, where the images and testimonies of the people on-screen — workers, scientists, a charismatic amateur rapper — are unforgettable.

— José Teodoro