Reviews include Superman, Apocalypse in the Tropics, and To a Land Unknown.

An Interview with Terry Chiu on Open Doom Crescendo and the Art of DIY

March 25, 2021

By Mark Hanson

Somewhere on the outskirts of Montreal, Terry Chiu is creating a cinematic experience of apocalyptic proportions. As he is one of the most exciting outsider artists to emerge on the Canadian film scene in some time, it would be a mistake not to pay attention.

Back in 2018, the 27-year-old writer-director appeared out of the ether with his first feature, the lo-fi coming-of-age comedy Mangoshake – a riotous blast of surrealist teenage anarchy mixed with the most mordantly funny existential musings this side of a Richard Linklater movie. While at first rejected by major film festivals, Mangoshake eventually found an audience at the Vancouver International Film Festival and Toronto’s own What The Film Festival (run by Peter Kuplowsky, lead programmer of TIFF’s Midnight Madness), spawning its own micro-cult both online and through a deluxe Blu-ray release via Gold Ninja Video.

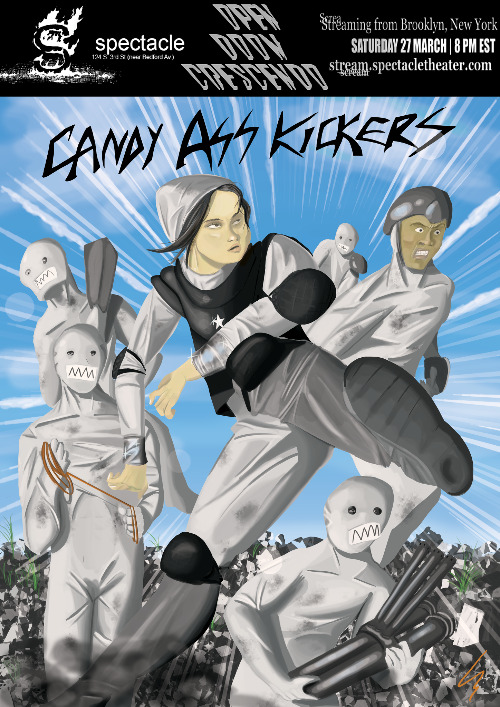

Chiu is now ready to let the world in on Open Doom Crescendo, his wildly ambitious follow-up project in the making. Planned as a four-hour, multi-chapter magnum opus about an array of strange characters wandering through an otherworldly wasteland in search of a cathartic entity called the Embodiment of Angst, it’s a massive undertaking that has spent years gestating feverishly in its creator’s head. With a completed 45-minute segment, referred to as ODC 21, now set to screen virtually this weekend through the Spectacle Theater in Brooklyn, NY, Chiu can finally give audiences a glimpse at what exactly this delirious, action-packed fantasia is all about.

I chatted with him ahead of the screening about his unlikely career path, the beauty of lo-fi filmmaking, the “romantic rupture” of suburbia and everything else you need to know to get acquainted with the Chiu-verse.

Your movies are such a blast of creativity, so original and unique…

Thank you!! This kind of validation, in a non-arrogant way, makes me feel like I can keep doing this and that I’m not some psychopath alone in my room…

Yet you very much operate in the realm of DIY/outsider cinema, which can be a hard sell to the masses. Have you found it harder than expected to get your work out there?

I was fairly aware that raw DIY filmmaking has a much narrower path to dissemination in the film industry, so I tried to walk a fine line between knowing what I was doing and the realistic chances of it getting out there. But I still disproportionately aimed as big as possible regardless, because I was coming from two worlds – acknowledging that I’m a DIY filmmaker but also wanting to somehow attack the game or the industry in a way to get this kind of creation as much as possible into the mainstream – which is a totally delirious thing, I get that. It’s not something you put down on paper as a healthy, sustainable career path, but I just thought there’s no other way I want to do this, so I might as well try it out.

I want to talk about the suburban environments that your films are set in. I come from suburban Ontario myself and it feels so familiar to me. Where are your films actually shot?

Mangoshake was shot in the greater Montreal surrounding areas, largely Laval and South Shore, as well as the anomaly of some industrial areas. My goal was to actually make it as un-Montreal, un-Canada as possible – not because I’m embarrassed of being Canadian. It’s more that I wanted to portray suburbia as abstract and universal an idea as possible. I wouldn’t want someone who isn’t Canadian to feel like they couldn’t connect, like how someone in Argentina couldn’t connect as much because it looks like an actor is clearly eating poutine.

You still make suburbia feel much more evocative than in a lot of other movies. It could be anywhere but it also has a specific sense of place. What is your connection with suburbia? Are you trying to highlight something or is it just a convenient location?

I actually didn’t grow up in suburbia. I’m from the East Side ghetto – my area is Saint-Michel, gridlocked between Saint-Leonard and Montreal North, of which the latter two extend to further North/East with Rivière-des-Prairies and Hochelaga. So depending on which West-ender you ask, they’ll likely either be shocked at how off the grid you seem or ask “where?”

When I discovered suburbia, that was a romantic rupture – like, “What is this clean-looking, grassy place with a giant mall where everyone hangs out?” At first, it was great – I’m going to hang out with all these posh cool kids, you know? Maybe I’ll belong here instead of having to fight and punch my way through the East Side. Suburbia was one of those seminal times of thinking that there’s some more romantic version of life that you can retroactively tap into. But then that’s a treachery because it’s a lie. It only exists for the people who were there to begin with, right? You have to be the rich kid with the pool in the back yard. I can’t recreate that. Even if you just tried or assimilated to fit in, you’re going to be dead inside. At least that’s how I felt.

When that rupture seeped in, I went back to the East Side more pissed off but with a newfound acknowledgement of where I come from and an awareness that I could honour and actualize from that source. I’m not romanticizing the East Side – rather, despite its urban grit, gloom, and dissonance, there is an earnestness and sincere vibe of communion in the places that matter. I find it with people like the very approachable Italian woman cashier at the supermarket, or the very personable francophone lady working at the dollar store, or the gangster Algerian garage owner across the street who’s always had my family’s back. I couldn’t find that in a well-adjusted, homogenous neighborhood.

This was the formative experience of honoring my lived urban experience through the raw yet sincere aesthetic and thematic ethos of my creative work. I’ll take dirty and real over clean and fake any day, whether real life or creation-wise.

So it’s pretty clear then that Mangoshake is a reaction to coming-of-age movies. Personally, I’m not a huge fan of coming-of-age movies because they generally offer just one perspective, one kind of environment, one kind of class level…

It’s a reaction to coming-of-age movies, but I’d be a liar if I said it wasn’t a coming-of-age movie itself. The script came about through the process of taking all these notes, anecdotes, random jokes, little threads, skits and just attempting to web it all together into something cohesive. And I was going through the whole romantic push-and-pull of the coming-of-age experience in my own life. Growing up, I had watched movies like Dazed and Confused and all these things that showed an experience that I didn’t get to have. That’s not what I lived. But it’s like you’re told by these things in pop culture that this is the experience you should live and if you didn’t live it, then you suck. And that could be fucked up for a lot of people growing up.

What struck me right off the top with Mangoshake was how it feels like it’s just a group of real teenagers getting together to hang out and make a movie over the summer.

One of the mainstay not-bad reactions I get is the response to the authenticity or the sincerity of it. I make it a point that, regardless of how I feel about it now or if I can’t ever watch it again, I take no ownership over its legacy because any minute group of people might know my name is Mangoshake. And that’s because they got something out of it. They got a lot of what I wanted from the beginning and then they got a lot of stuff that I wouldn’t have even expected them to get out of it. If you look at the Letterboxd reviews, some people are appalled or disgusted by it and I can’t even get that upset because they still paid for it, so it’s a fair trade.

No refunds…

So either they hate it or they really liked it or they have an existential crisis over not being sure whether they hated it or liked it. No boring middles, right? But the through line of all those reviews is the acknowledgement of the authenticity. I remember one reviewer was like, “It was just a bunch of kids who just came together and made a movie. Oooo good job” or, “I hate it, but this is what it’s like to come together and just make something.”

Well, as someone who made a lot of movies with my friends in suburbia as a teenager, your stuff is way more advanced creatively and thoughtfully than anything I ever made. Your work is also pretty existential – from watching it and talking to you now, you seem like a pretty philosophical type of guy.

It’s largely a cover-up for the fact that I don’t know a lot of academic stuff. I think that I’m just a notoriously stupid person and that my way to reconcile that is to go all-in on the abstract stuff, on the things that don’t require parameters. It’s why I’m in art; because in science, you’ve got formulas and all that. If you get the formula wrong, you create a bomb or a mutant monster. With cinema, if you screw it up, you’ve just made something really shitty so the stakes are way lower. Like the worst is that you really upset people.

I think it’s a mix between reconciling my lack of being good at anything else and my natural interest in these things. From a young age, I just cared about creative, abstract experiences in a way that I think is very self-alienating from people who actually know things. And then because I just focused on that, I never had the attention span to learn different parts of the globe or the map or history. I can’t retain information that well but then the information that I do retain is completely selfishly specific.

Let’s go into Open Doom Crescendo. Mangoshake was already super creative and ambitious and this is even more so. And where Mangoshake still has the semblance of a story line, ODC is completely experimental and almost rejects narrative entirely, while also incorporating genre elements. What was the genesis of this project?

I actually feel like ODC is the one with a clearer story, though that’s been argued over amongst the team. The genesis came during the autumn following the summer shoot of Mangoshake in 2015. In that time in the fall, during picture editing, I quickly got the dread of knowing that this is what I’m going to be looking at and working with for a very, very long time. And already, it felt like this was going to suck. I just didn’t even believe in it. I was already ruptured from the romantic packaging aspect of it – the coming-of-age, rock ‘n roll packaging that you get going into it. Even though the point is to get underneath that, you still have to get through the superficial quality of it to get there. That just got to me.

I actually feel like ODC is the one with a clearer story, though that’s been argued over amongst the team. The genesis came during the autumn following the summer shoot of Mangoshake in 2015. In that time in the fall, during picture editing, I quickly got the dread of knowing that this is what I’m going to be looking at and working with for a very, very long time. And already, it felt like this was going to suck. I just didn’t even believe in it. I was already ruptured from the romantic packaging aspect of it – the coming-of-age, rock ‘n roll packaging that you get going into it. Even though the point is to get underneath that, you still have to get through the superficial quality of it to get there. That just got to me.

ODC was emotionally the result of me needing a reason to convince myself to finish Mangoshake so that I could get to the next thing. I was already thinking, “What’s the next thing I want to say?” ODC was basically my end goal. I knew if you got something out of Mangoshake, I can’t imagine what you’ll get out of something I actually like doing.

My feelings on ODC have not changed. It’s the first time I’ve maintained a passion about something the whole way through and unabashedly believed in it. So even from its inception, I knew this was it, at least for this part of my short-winded life. Mangoshake was cool to make and I wanted it to be iconic, but there were all these things that took away from the fully realized resonance. But ODC was the destination.

So would you say this is more raw, unfiltered Terry Chiu than before?

Oh yeah, but I really don’t want it to be about my name or my association with it. Mangoshake was a compromise between the reality of being a captain, a director, as far as the term goes, of a project. And if the creativity roots back to that person, they need to take it to finish line. Mangoshake was a learning curve of having to just accept that and assert that while also dealing with all these first big collaborations with people. That’s when you find out really who you’d want to work with again and who you wouldn’t. So there felt like this obligatory need to assert this level of ownership over Mangoshake.

If I had it my way, I’d be okay with people never knowing who I am. All I want is the money to live off. I just want to do this and not have to think about what food I need to survive on, whether it’s going to be yogurt tubes or breadsticks. My bar is so low in terms of my physiological life. There’s a reason why my name’s not on the poster and when it comes time to put it in the credits, I just kind of squish everything together.

You do have a line in the credits stating that everyone on the cast and crew chipped in the same and no one is above anyone else during the production.

The aftermath of Mangoshake was a purge of what came before. What’s left are the people who stick around when I’m in the worst of the pits. Out of that comes this trust that you don’t get with casting calls or with hiring people you don’t know. Being able to trust the people I was doing ODC with allowed me to be at peace with the fact that I’m part of a larger cultural discussion of auteurism and indie filmmaking. But this was an opportunity to navigate around that reality. I have a bit of leverage now and I’m happy about that, but I want to use it to propose a different way of creativity as community.

Going back to the suburban aspect of your work, that environment acts as the perfect backdrop for this weird post-apocalyptic setting.

I really wanted to mitigate the suburbia-ness of it in an attempt to portray this gravel, terrestrial void. But if you look at the surrounding edges, it’ll definitely still look like suburbia…

I love that, though – how you always see the rows of townhouses in the background but the characters don’t really see them.

There are a couple shots that really tickle my funny bone. There’s one scene where we shot in front of a street and, there are cars going by in the background. So clearly there are people alive and well and doing their thing in this post-apocalyptic setting. Again, it’s not the focus – even though you see a plane flying by, it’s part of that humour. You get the point but it’s also not trying to be ironic about it. It just happens that we don’t have the budget to not have planes and cars in the background.

It speaks to the DIY nature of it and the fact that you don’t need to make it look like some perfect cinematic world to get the point across. If anything, it adds to the film for me.

To me, Mangoshake actually looked [like] it had high[er] production [value] than you’d expect from a lo-fi movie, so I wanted to rectify that with ODC. Mangoshake was shot on a reasonably pricy camcorder. It’s not Hollywood-level but it’s the Sony EX1 that was borrowed from someone’s dad. I was thinking that because it’s our first feature, let’s make some kind of technical impression, even though I still wanted to be at the edge of that technical HDness. With ODC, I went all the way back down to the Canon Rebel T2i, to make it come off a lot rawer and home-video-like.

I want to ask about the subtitling work in your films too. It was used to hilarious ends in Mangoshake and you take it to a whole other level in ODC, creatively subtitling the entire film in both English and Japanese. In a film full of crazy aesthetics, it’s one of the craziest.

The impetus of subtitles with Mangoshake goes back to the first cut when I was told it was hard to hear certain things. So I went on Premiere and hard-burned the entire movie, which was a miserable experience. Later, we had the idea of getting someone to do a better subtitling job and stylizing selectively. It was a way to marry the rough sound with the lo-fi aesthetic, so it became this quasi-self-aware thing that said, “Here are subtitles to assist but they’re stylized enough to look like a deliberate thing and not just a band aid.”

With ODC, there hasn’t been a professional sound mix on it yet and by this point, I know my track record of “hard-to-hear” sound. But I also wanted to take it a step further and do it in Japanese too. I wanted to evoke the inspiration of Asian media and create this lo-fi international VHS vibe, like a movie that’s discovered from the rubble of a world cinema section. And the response has been unanimously positive that it adds to the iconography of it.

The benefit of making lo-fi stuff that’s duct taped together is if you find a way to make it work and own it, then you’re creating a new compassionate level of storytelling – the fact that we did it despite the technical limitations. It all roots back to this sympathetic language of the creator communicating to the audience without winking and breaking the fourth wall. You can know you’re watching a movie without it being an ironic cynical exercise. It’s like Zack Snyder said, and I’m paraphrasing, “You can have fun with it, but you can’t make fun of it.” It’s a fine line you walk, right? The second you stop believing in what you’re doing, how can you expect an audience to embrace it? People can tell if you’re sincere or not and that’s what stays with you. I want that to be my lasting goal of making things, where the fundamental goal isn’t how much of it conventionally “works” but rather, that it got across a meaningful ethos.

So how much work do you have left on ODC? This part is only 45 minutes but I know it’s part of a larger almost four-hour final version.

We’re supposed to shoot this summer so I’ve been deep into pre-production for that. Out of the abstract, four-hour runtime, about 55% of it was already shot back in 2019 and a bit last summer. The rest of it has just been waiting to get done but it’s always been happening. It’s not something that’s just on paper. This is the surest I’ve ever been in my short-winded career that something could come out of this that could matter.

ODC 21, which is the part people are seeing now, is something I really believe in. It’s still the riskiest episode because of its self-contained construct from the big picture. Plus, it’s way more talky and existential and seemingly nihilistic than the larger picture.

So this is basically a teaser for the larger thing…

Yeah, it’s like a retro-prequel-pilot thing because it takes place before the rest of the chronological narrative, even though it’s actually the second part of a seven-part section of the narrative. But because of the world ending, it just worked out that the one part that was finished is the only self-contained part.

It reminds me a bit of Richard Kelly’s Southland Tales, where the initial film was purportedly part of a much larger project. But in that case, it never really came to total fruition, whereas you’re very much on your way to creating this epic cinematic experience.

I’m grateful that this is happening because right now I don’t have a four-hour thing that I have to convince people to give the time of day. I’m not Zack Snyder – I haven’t earned the track record for people to trust what I want to do on bold, operatic levels. I humbly need to work my way to that. This has become an opportunity for ODC to exist as an ongoing thing, rather than something you just hype up with nothing to show for it. There’s evidence that this was a legit operation. And as a nobody creator, it matters for me to acknowledge that and take that approach.

Open Doom Crescendo 21 screens Saturday, March 27 at 8pm through the Spectacle Theater’s virtual screening room on Twitch.tv. The project is also on GoFundMe to aid in the completion of the final version. Mangoshake is available to purchase on Blu-ray via Gold Ninja Video.

Mark Hanson is a winner of the 2020 Cineplex Emerging Critic Award.