Reviews include Civil War, In Flames, and The Greatest Hits.

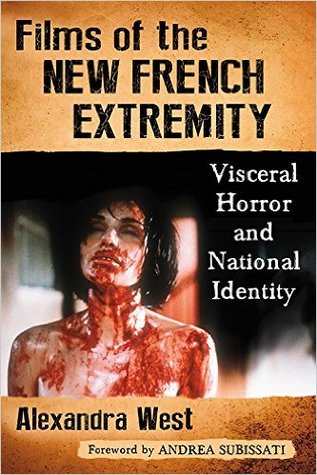

Visceral Horror and National Identity: Interview with Alexandra West

September 21, 2016

Based on her new book, Toronto-based film critic Alexandra West has a bone to pick with James Quandt, whose seminal 2004 Artforum article “Flesh and Blood” put a label on a certain tendency of early 21st Century French cinema – a relentless focus on the body and its various vulnerabilities, depicted via variably radical aesthetics.

Quandt called the cycle of films that appeared in this period “the New French Extremity,” and while his descriptions and analysis of the films was brilliant – so much so that the piece quickly entered the canon of great contemporary film essays – there was a sense of anxiety apart from the often unnerving qualities of the movies themselves. In noting the increasingly intense bent of works by auteurs like Claire Denis, Bruno Dumont, and Olivier Assayas, amongst others, Quandt sounded as if he was worried that these vanguard artists were somehow lowering themselves to a baser level of expression.

By contrast, West’s book holds these movies up as exemplars of a long-running Gallic tradition of measured transgression, and argues that the more commercially-oriented productions that followed in their wake are worth taking seriously as well. Subtitled Visceral Horror and National Identity, Films of the New French Extremity is a model of accessible, intelligent genre-film criticism, and West’s rigorously researched accounts of movies from Philippe Grandrieux’s haunting Sombre to Pascal Laugier’s infamous Martyrs address style, symbolism, and reception with clear enthusiasm and aplomb.

Adam Nayman spoke to Alexandra on the eve of her book launch in Toronto.

Adam Nayman: One of the things that’s very ambitious and exciting about your book is that it’s basically a Canadian film critic engaging in an argument against James Quandt, or at least trying to go further than he did in taking the idea of the “New French Extremity” seriously, and applying it beyond the initial small group of art filmmakers.

Alexandra West: I fell in love with New French Extremity after I saw Martyrs and Inside, and after I re-watched High Tension, and then I went back to Artforum and read Quandt’s piece which named the movement for the first time. I thought it would be this enthusiastic overview of a cycle of films, and I was shocked at how negative he was being. His follow-up article a few years later, which is called “More Moralism From That ‘Wordy Fuck,’” doubles down on the same attitude as well. I thought there might be some give and take by then, or some change, but there wasn’t, and I thought that it was unfair.

AN: I think Quandt saw this new style as an incursion on the territory of art movies, or maybe as a pollutant. But what’s funny – and what you point to in your book – is that as uncomfortable as high-end critics might have been seeing Claire Denis make a vampire movie, genre movie audiences look at something like Trouble Every Day and don’t know what to make of it because of how oblique and bizarre it is in terms of style or sensibility. It’s a movie that can make both cliques anxious.

AW: They’re all sort of like island-of-misfit-toy movies in a way. They’re hard to place, and we as a culture like to try to place things within boxes and say “this is this.” This examination of New French Extremity for me was sort of asking “well, what is a box?” And: “can you redefine that box every so often?”

AN: Your box has some very nice compartments; you group the movies very effectively. What’s great is how you write very seriously and perceptively about Denis, and Bruno Dumont and Philippe Grandrieux – these experimental, boundary-pushing artists – and then apply the same seriousness to the less-heralded filmmakers who follow them, or who made more commercial work as the 2000s went on.

AW: I was familiar with some of the films before I wrote the book and I was watching many others for the first time, and the connections between them became quite apparent. These paired chapters made sense because it was a way to help the films talk to one another, and I do think that they really do talk to one another, all of them, even if it’s on a subconscious level, communicating themes and ideas that illuminate parts of France. And they’re the parts of France that nobody there wants to talk about.

AN: Was it always the idea to open with a survey of French history and culture? That could be daunting for readers who just want to get straight to the films themselves.

AW: It felt a little risky when I was talking to colleagues about wanting to discuss French history and the history of the French film industry, and they had a weird reaction it. But I wanted to read and write about that history, and if I can learn about it then I thought everybody else should, too. I think those chapters have gotten some of the strongest reception so far.

AN: You bring up Eyes Without a Face early on, and that seems like a major influence on some of the New French Extremity films, especially because it’s so deeply political: it’s a movie that uses the metaphor of a woman getting a new face to allegorize the occupation of France by Germany, and the Nazi eugenics experiments as attempts to create a pristine Aryan surface. It’s an amazing film and a haunting reflection of its era.

AW: There’s the same DNA, I think, in the newer films. I had seen Eyes Without a Face before, and I felt like I could link it to Martyrs, because in a way they felt the same. I wanted to know what the connection was, and I saw that really what there was was not a connection but a gap. To my mind, what the French cinema was missing – what it didn’t have – was something like the New Hollywood in America in the 1970s. We didn’t have that either in Canada, really.

AN: The ’70s in France were all about the aftershocks of the New Wave, and the Cinéma du Look was still years away. In terms of genre or vanguard-pushing new work, it really was comparatively barren. And so the arrival in the 1990s of these tougher, more shocking movies did feel like a big deal.

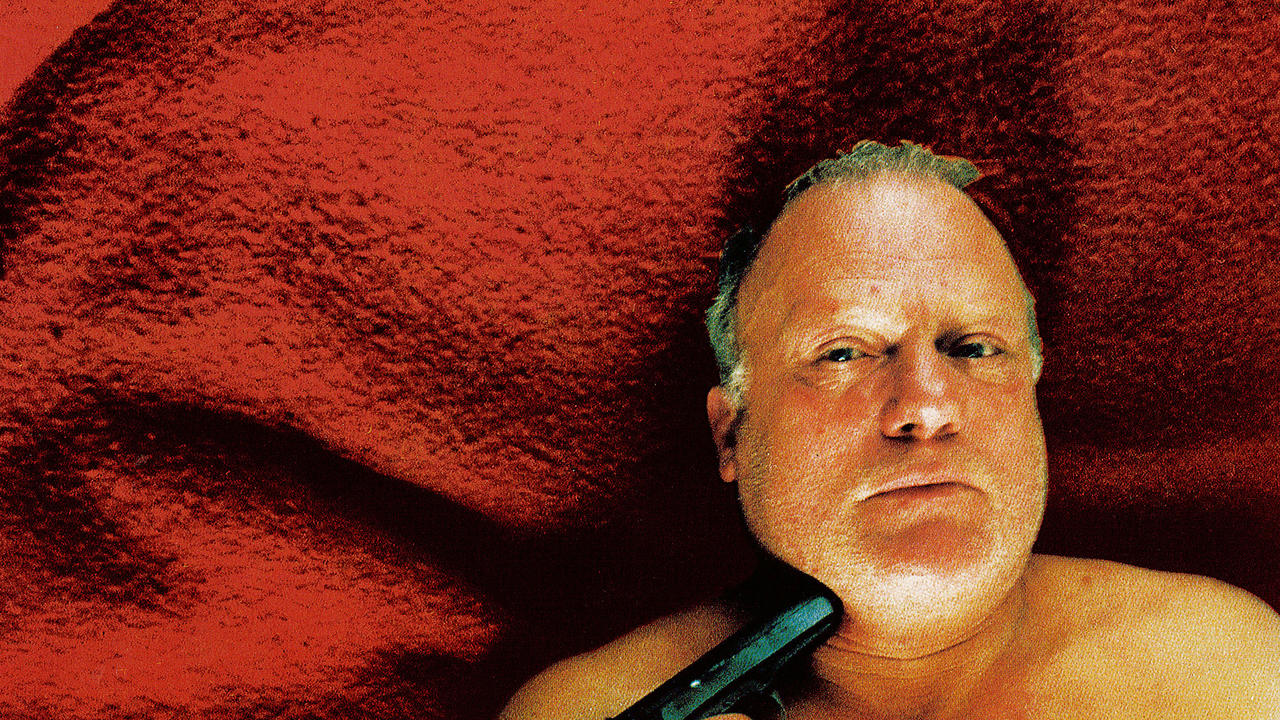

AW: Yeah, when I saw Gaspar Noe’s I Stand Alone, I realized it was France’s Taxi Driver, twenty years after the American one. Taxi Driver was so important to the cinema of the ’70s in the US, and that’s the same for I Stand Alone in the ’90s in France.

AN: Gaspar Noe is a 70s-ish figure if only because he seems able to attract controversy. Irreversible was a big deal when it came out, and people freaked out about it in the same way as The Wild Bunch or Straw Dogs or A Clockwork Orange. It was a scandal.

AW: If I mention Irreversible to somebody who is even a minor film buff, they’ll immediately say “oh yes, that French rape film.” It’s a weird touchpoint in that way. I think that Noe is a transgressive artist, but there’s also a naiveté and a purity that’s rare and that I really respond to.There’s a lot of chutzpah in his films and how he conducts himself. When I sat down to interview Colin Geddes for this book, he told me a lot of anecdotes about Gaspar and what a lively, childlike person he was.

AN: I think that’s what Quandt was concerned about – that these very canny, savant-type guys were going to spring up in the wake of what Denis and Dumont were doing. And he also didn’t really like what Denis and Dumont et. al were doing, either.

AW: I’ve found as a horror film journalist that people love to deride genre. Quandt saw a kind of promise in [Dumont] and was horrified that he would choose to do something like Twentynine Palms, which I think was the last film I watched before writing the book. I had expected the film to be intense, and even so it’s the most affecting film I’ve ever seen. It truly shook something loose in me.

AN: He’s playing with genre tropes in that one, and using them very strategically to fuck with his audience. And like Antonioni making Zabriskie Point, he uses California as a lunar backdrop.

AW: I do think that Twentynine Palms is the perfect intersection of New French Extremity in that it has this extreme violence and sexuality, and they meet in that blank, nihilistic landscape. He was experimenting, and when critics tell directors who are experimenting “don’t do that,” it’s problematic.

AN: You write at length on a director who I think is in many ways equal to Dumont and Denis but rarely gets mentioned alongside them: Philippe Grandrieux. He’s this incredible, visionary artist, and he’s not really known in North America outside of hardcore cinephile circles. Sombre is a fascinating movie, and I was happy that you included it.

AW: It took me four attempts to watch Sombre. I couldn’t get past the first ten minutes each time. I’d never had that problem with a movie before. On the fourth time it clicked. It’s this weird, hypnotic movie, like being in a sensory deprivation tank. It’s disappointing that more people haven’t seen it, or that he hasn’t been picked up more.

AN: Grandrieux is so radical – much more than some of the directors who follow him in your time line. Without disrespecting the argument in the book, which is that even the more popular, accessible titles have political or cultural value, I will say that I think the idea of extremity moved pretty swiftly from the form of the movies to the content. It became less about playing violently with aesthetics or conventions than just using genre to deliver images of great violence.

AW: The second half of the movement did change like that, but one of the other things that happened is that the films actually got more overtly political in the process, like in Frontiers or Inside, which takes place against the backdrop of the banlieue riots. Or in Ils, where this couple is trapped in another country, which is very significant. These movies use tropes to mask their insides, or they use horror as a Trojan horse for ideas. Blood and guts is like the spoonful of sugar that makes the medicine go down.

AN: People wonder, though, if that extremity is always a case of an artist with something to say, or if it’s pandering to a marketplace.

AW: Because of that broken horror tradition in France, it’s like they were catching up all at once, making a lot of movies. France was consuming American culture, like slasher films, and so there was a need for creators there to start engaging with the material as well. Each degree of separation from American culture with this stuff adds a different lens, or twists or fractures it.

AN: Well, if a film has subtitles, it’s an art film in North America. Inside didn’t play at multiplexes – it played here at art-houses.

AW: These were not always easy movies to get made [in France]. The importance of tax credits and co-productions is a big thing. Canada was a co-producer on Martyrs. But another big influence is TIFF, specifically Midnight Madness, which has brought a lot of those films and filmmakers to North America for the first time. Seeing a movie with that crowd is a totally different experience, and if you can get the right people in that theatre it’s a game-changer for distribution.

AN: You use the French writer Antonin Artaud and his Theater of Cruelty as a structuring element in the book – how did you first encounter his work and ideas?

AW: That all came from my background in theatre. I did my undergrad and my Master’s in theatre, and I always loved the Artaudian philosophy, and the Theatre of Cruelty. I loved hearing about how that work had been staged, but it always sounded pretentious, and in a way that his own writing didn’t. What I wondered when I started watching all these movies was: what is in the soil in France that can generate all of this cruelty and all of this violence, for Artaud and for these directors? What is leading to this sort of work?

AN: I think that some of the movies you’re writing about are essentially quite pretentious, but that falls away because of how visceral they are. The physical overwhelms the cerebral, or maybe cannibalizes it.

AW: Taboo and transgression is always tied to satire and mockery. I love how films and [theatrical] plays can show how quickly divisions crumble. Everything falls apart. The myth of France as romantic and egalitarian – it dissolves in these movies. These films are a bit like King Lear, standing in the wind and screaming.

AN: Did you grow up on horror movies? I used to go the corner rental store and take home as many disreputable-looking VHS cassettes as possible.

AW: My parents used to give me ten bucks a week for allowance, and I’d go to Rogers which had this deal for seven movies for seven days for seven dollars. I’d come home and tell my parents that I was just going to go to my room and read and watch horror films and they were like “that’s all?” Little did they know. But they were always supportive, and that’s why the book is dedicated to them. Although when I was done, my mom told me she was glad because “I looked like shit” the whole time I was writing – she meant because the movies were so depressing. It’s not always the easiest stuff to write about.

AN: How do you not grow desensitized to it? Are there films that broke through that gore-fatigue for you, even now?

AW: With Inside, for example, I’d already seen it maybe four times before I wrote the book. I thought I should look at it again with some new notes. I was home alone, and the movie started, and it was upsetting, and the scene at the end with Beatrice Dalle rocking back and forth in the chair… I just inexplicably got so terrified. I was locking my doors and windows, it was really frightening. And then there were others, like High Tension, that were just old hat to me at this point.

AN: The book has Trouble Every Day on the cover, as

AN: The book has Trouble Every Day on the cover, as

it should. That feels to me like the true

masterpiece of New French Extremity, whether or not it even belongs in the category.

AW: I love that film, very much. I was so pleased with the cover image for the book. I think Claire Denis is brilliant, and an incredibly interesting woman. There’s a totally uncompromising aspect to her cinema. When you set out to create something scary, like she did in Trouble Every Day, it’s always about what scares you personally. That process is always politicized as well.

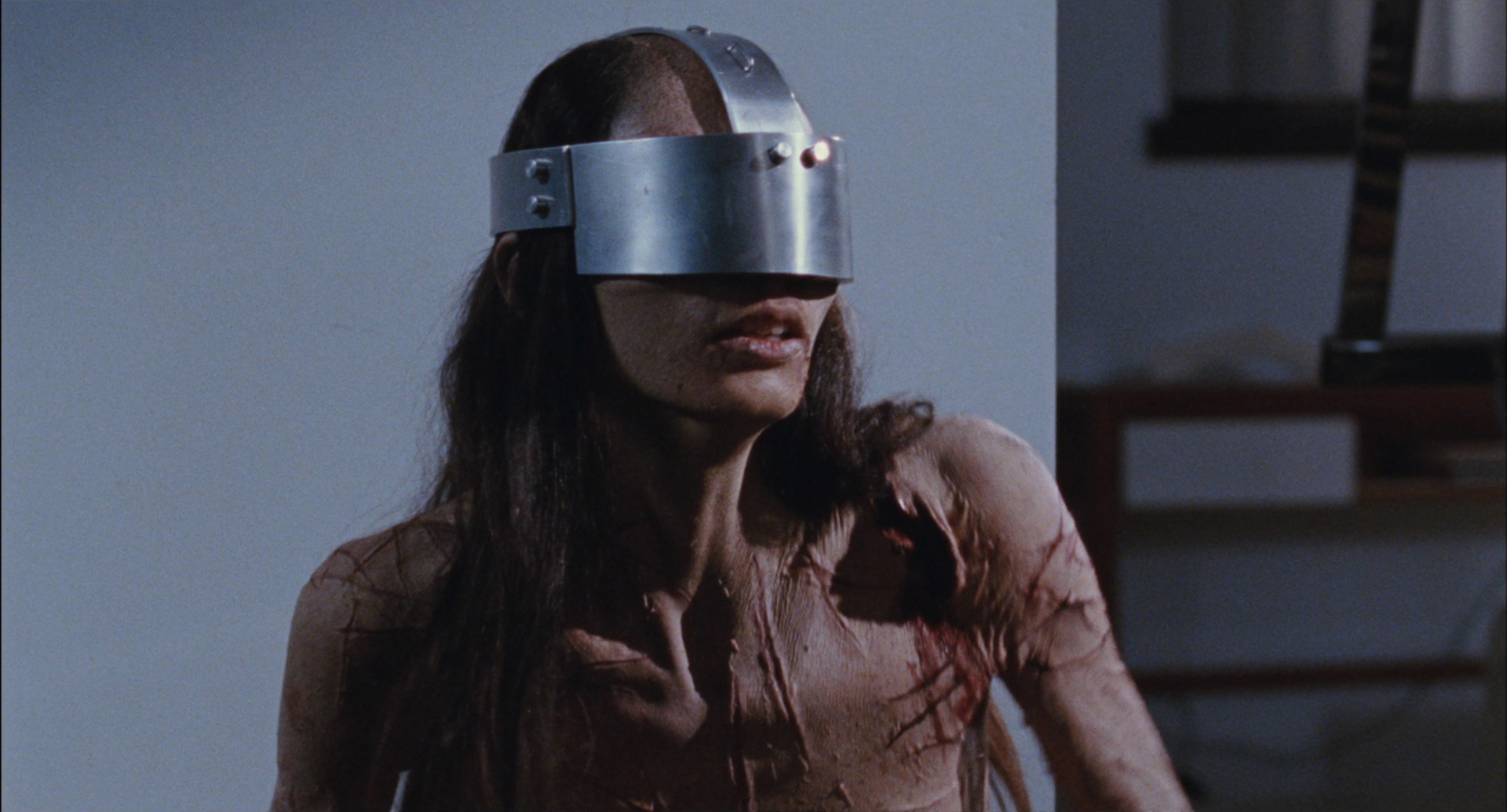

AN: The image on the cover is phenomenal – it’s this post-feminist image, very dangerous, but the empowerment is complicated because in the film Beatrice Dalle’s character is basically in thrall to her urges, totally mindless because of this vampire virus she’s infected with. She’s iconic, but it’s also resonant in several directions at once.

AW: She’s a beautiful woman, covered in blood, but not screaming. She’s in ecstasy. It’s such a confrontational image, and it’s everything the book is about. Sex and violence are our most natural instincts, and so they’re what we always try to suppress the most.