Reviews include Deadpool & Wolverine, Doubles, and Mountain Queen: The Summits of Lhakpa Sherpa.

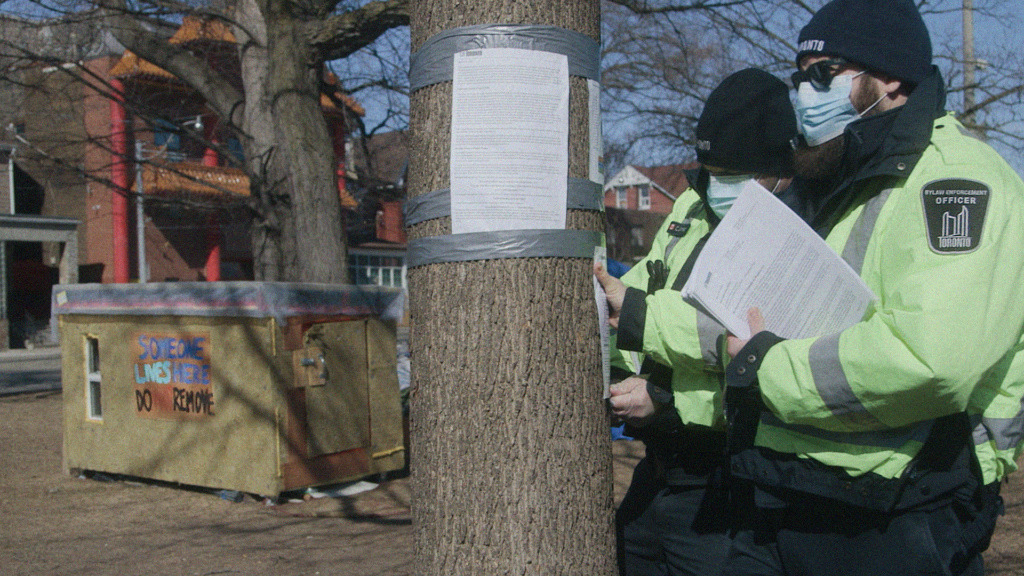

When Someone Lives Here’s Zack Russell Discovered He Made a Movie

February 22, 2024

By Thom Ernst

Zack Russell is coming to terms with the realization that he has made a film. The first inkling was when his feature, Someone Lives Here, premiered at the 2023 Hot Docs Film Festival. It won the Rogers Audience Award for Best Canadian documentary. Then came other nominations: a grand jury prize at DOC NYC and two nominations from the Director Guild of Canada, one for editing for Marianna Khoury and an Allan King Award for Excellence in Documentary for Russell.

Russell had no choice but to accept that he accomplished what he set out to achieve: to make a film about the under-housed in Toronto.

Russell had been plotting out the details for a fictional story of homelessness when he came across the story of a carpenter named Khaleel Seivwright. Seivwright designed and built temporary shelters for the unhoused. But when Russell approached Seivwright, the carpenter wasn’t interested in being in a documentary. However, he did want an instructional video on making the shelters.

The film that instructional grew into now has an 8.7 audience rating on IMDb.

Someone Lives Here is nominated for the coveted Rogers Award for Best Canadian Documentary to be presented to the winner at the upcoming TFCA Film Gala on March 1st, 2024. The prize comes with $50,000 for the winner and $5,000 for the runners-up. Also nominated is director Chelsea McMullan for Swan Song and director Zaynê Akyol for Rojek.

Russell talks about the underhoused, and the unexpected grievances aimed against Seivwright for his efforts to shelter the unhoused during the winter months of the pandemic. As much as the film can inspire some to rethink their perception of the underhoused, it can provoke the naysayers: City councillors genuflecting to policy, conflicted bystanders who empathize, but adore their un-tented public parks, and health and welfare watchdogs finding potential hazards within every wooden shelter.

Russell also talks about making a film and the mysterious world he now finds himself in—a world of accolades and film awards.

Thom Ernst: There is an under-housed problem in Canada. It’s a big issue in Toronto. We have the underhoused, and they need a place to stay. Your film Someone Lives Here introduces us to a wonderful man, Khaleel Seivwright, who’s doing something about it by building self-contained shelters from the elements, including the cold. An immediate solution for an immediate problem. And yet, your film does not escape criticism for its humanitarian efforts.

ZACK RUSSELL: What’s interesting is I just did an interview on the radio. I won’t say who with, but I did some AM radio interviews last week. And we did have a whole exchange about the film. One of the things that I mentioned in the exchange was (that) these were essential shelters from my point of view and from many people’s points of view–to keep people alive and safe. The issue with them was really one of NIMBYism from neighbours as well as the city government wanting to control these public spaces.

Some councillors waver. Some councillors are much more staunchly opposed to them and cite reasons of fire or safety, this kind of thing.

In the (AM radio) interview, we have this whole exchange, and I’m explaining my perspective, then she mutes me, and she says, “I completely disagree, and I think that we can all agree these things were very unsafe, and it was a bad idea.”

And I’m like, “Oh, is the interview still going?” And she’s just moved on. That’s her cap for the interview. And then she keeps going. So, it’s fun when I have a chance to address them, and I’m not just muted.

The issue of homelessness, fundamentally, is a societal choice that we’ve made, that it’s acceptable. You can criticize the means with which people are trying to solve it, and that’s fine. But I think there’s an underlying idea that it’s not anyone’s problem. It’s not the city’s fault. It’s not the neighbour’s fault. It’s not my fault. It’s not your fault. Having made the film, I fundamentally disagree with that. I feel as though it is everyone’s problem because I don’t think that we should be living in a society where homelessness is this institutionalized thing that we’re all okay with.

And so I’m fine with criticisms of Khaleel’s efforts. I’m okay with criticisms of the film being too biased. But I think, for me, it’s an issue that demands action. If you want to criticize my actions or those of Khaleel, sure. But then offer something better. And when I say better, I mean something fast and effective, not something 10 years down the line, or a promise of funding or blame [on] another level of government. The criticisms are acceptable because I feel quite staunch in my belief that this issue needs immediate action.

Was it staunch at the beginning? How did you enter this?

I entered it naively, and I had no idea that there would even be opposition to these tiny shelters. That’s how naive I was when I started making the film. I thought that these were just a good idea. An unqualified good idea. The staunch support of them only came through seeing the effect they had on people’s lives and seeing the negative reactions of housed neighbours and local government.

On the one hand, people really need and benefit from them. And then on the other hand, people who have no experience of being homeless critique them. And that’s when I thought, “Who do I trust in this matter? The homeless people because they’re the ones we’re talking about”: So, it was only through the experience of making the film and seeing the effect it had when people got these tiny shelters that I became such a staunch supporter of it.

You include one oppositional voice. Their ideas seem to be quite limited, maybe even self-centered. The ‘not in my backyard’ argument. How did you choose to deal with that character? You weren’t cruel. You didn’t set her up. You didn’t “Michael Moore” her.

I was grateful and excited that she was willing to talk. I think because we live in a progressive Canadian society, we are all terrified of saying things that will cause offence. I felt like I found this gem of a person. It wasn’t that she didn’t know that these things were offensive or controversial; she felt so passionate about them that she still wanted to speak about them. She has a courage that I think many people don’t have. I was very excited by her courage to say things she disagreed with. I also feel I adopted Khaleel’s ethos: “Better to hear the negative things than to have them be silent and to pretend that the issue is something else.”

I wanted to hear the truth from people, and I felt like she was giving me her truth. I don’t think she was spinning it. I don’t believe she was sugarcoating it. I was so happy and passionate about including it. There were other people we interviewed who had more nuanced, complicated, negative ideas about the tiny shelters and people living in parks. None of them, I think, spoke as honestly as she did. We’re limited when we don’t have a fuller picture. I think when people watch the film, they will want to distance themselves from her. Often, they want to say, “This woman is terrible, and I’m not like her.” They’ve been given a fuller picture, so they see her now in a picture with other elements and can then say, “Not that, but this.” But unless you have a picture where you have all of these elements, you can’t really make a decision for yourself.

One of the fears watching the film was recognizing my limitations towards understanding the underhoused.

I would say it’s just a lack of exposure issue. I mean, the sad but ironic thing about our society is that you can be living downtown next to homeless people and still not really be exposed to homelessness. You can turn a blind eye and not really engage. And if you don’t form a meaningful relationship with someone who’s living outside, it’s hard to really understand what it is. It’s not just about living in proximity.

How did you encounter Khaleel?

I was trying to write a fictional film about homelessness. I think part of the reason for that was living in Parkdale, having a lot of interactions that were really superficial with people who were unhoused on the street, just passing them by, giving them a couple dollars, seeing them around. And then the other thing is I had always had this premonition about an individual in my family and a fear that someone in my family was maybe homeless and we’d lost touch for many years. I had this lurking question: is there someone homeless in my life that I don’t know?

That’s an interesting starting point. Have you discovered anything more about this phantom person that may or may not be in your family?

Yeah. My fears were somewhat accurate. It (felt) a little bit like, through making the film, I (had) prepared myself to better support this person in my family. I feel like I gained an understanding and a skill in working with these people when making the film, and then when it came to my own family, I had a much more precise and focused perspective on how I should help and what I could do.

I’m a bit stunned by all this as, as someone relatively privileged in all aspects, I have a house, and I love my view from the back window. I don’t know what makes a person like you have such selfless priorities. It’s a bit astounding to me.

I had parents who were social workers, and my father worked with homelessness, and the lurking feeling that someone in my family might be homeless was in the conversation for me in a way that I never fully recognized until I made the film. So, it is not as astounding as it seems.

Well, because you’re from the inside. When you’re on the outside looking in, it’s damn astounding. I know from experience that when the opportunity to stand up and act is available, it’s just as easy—to ignore it. But watching your film makes it more challenging. It makes it harder to ignore these things and makes you confront the issue: are they safe? Are they a good idea?

I think a million cues in society tell us to not help. It’s not uncommon to just walk by and to ignore. And, of course, I’ve done it a million times too. However, I think it’s cool to try to make things that challenge that. And I think we don’t need more things telling us to make money, fend for ourselves, and tend to our own family at all costs.

What about new Canadians, immigrants, and refugees?

I have a visceral reaction to people that are around me suffering. And I think the film has heightened that, so I don’t care where you’re from. My consciousness goes to the city limits. If you’re in my city, I now feel a responsibility. If you’re a bunch of refugees in the city, you’re in the city, you’re near me. So much of the film is about helping people you can see and meet, right?

It’s not a film about helping people living on the other side of the world. That would be a very different film. I feel like my ethos around it is taken from Khaleel; if you see someone, you can do something for them. I think that’s the kind of help that I trust the most at this point. Having made the film, I don’t know how I feel about trying to help people halfway around the world. That seems more complicated. The immediacy of mutual aid is very appealing, making a lot of sense to me.

Khaleel seems like a magical person human being. Yes?

Uh, no. I don’t think he would appreciate that description–no, not magical. I think that he likes to see himself as reasonable. It’s similar to how people talk to him about being an activist. Implying that he’s different from other people bothers him because he feels like he’s actually just very reasonable; his actions are reasonable, and the things he cares about are reasonable. I don’t think he wants to be this magical genius who’s off on the periphery. He wants to say, “What I’m doing should be the center of what we’re all doing.” Which is a kind of magical thinking.

The irony is that only exceptional people think that way.

He’s definitely exceptional. But the thing that really appealed to me about Khaleel was his work ethic and how hard he worked. And I think a lot of people work really, really, really hard.

What are your thoughts on the nomination with the TFCA?

Great. I should confess that I haven’t been super aware of all of these awards that we’ve been winning. They weren’t on my radar before. I think I went so far as to get into a film festival, and then my imagination stopped. Probably because it’s my first feature. You don’t know what you don’t know. I don’t know what it means, other than that a bunch of critics liked it. Yes?

Yeah. A bunch of critics like it.

That’s nice. I mean, my fear in making the film was always that I was not really making a film, and I was just helping people. It is nice to have it recognized as a film that also works and that the film itself has some value. Because it felt while I was making it that maybe this wasn’t even a film. The question of whether it was a film and was it a film that would work haunted me until we screened it at Hot Docs. To have people continuously telling me, “No, this is a film, and this is a film that we would like to watch and that we think something about.” I don’t know. It feeds something in me.

Would you still consider making that fiction film about homelessness?

Yeah, I’m working on it now and working with a lot more experience behind me.

Perfect. And I’m interrupting it.

You’re interrupting it terribly. [Laughs.]

Someone Lives Here is now playing in select theatres.

The winner for the Rogers Best Canadian Documentary will be revealed on March 4.