Reviews include Irena’s Vow, The Beast, and Before I Change My Mind.

Chelsea McMullan’s determination, stamina – and basketball experience combine to create the superb Swan Song

February 20, 2024

No pain, no gain. That’s a sub-theme of Chelsea McMullan’s gripping documentary Swan Song. The film, undertaken over a three-years-plus period, offers an intimate account of the creation of the National Ballet of Canada’s epic production of Swan Lake, helmed by the iconic Karen Kain, and which opened in 2022. The film is one of three nominees for the TFCA’s new Rogers Best Canadian Documentary award, which carries a cash prize of $50,000, courtesy of Rogers. Also nominated are Zaynê Akyol’s Rojek and Zack Russell’s Someone Lives Here.

McMullan and their team track the intense rehearsals, how the ballet’s physical demands challenge the dancers, the injuries they incur, the perils of heavy, complex costumes, artistic differences between dancers and their director and the hopes that it will all culminate in a gorgeous performance.

“We [meaning McMullan and producer Sean O’Neill] had a motto that we consistently followed,” McMullan recalls of the demanding shoot: “all the beauty and all the pain it takes to perform this inhuman movement onstage. It’s almost other worldly.”

Not that it’s the first time we’ve seen ballet dancers bandage and massage their feet after a performance. And most of us know that ballet requires contortions and movements that the body – a woman’s body in particular – is not designed to do. Toe shoes seem calculated by a true sadist.

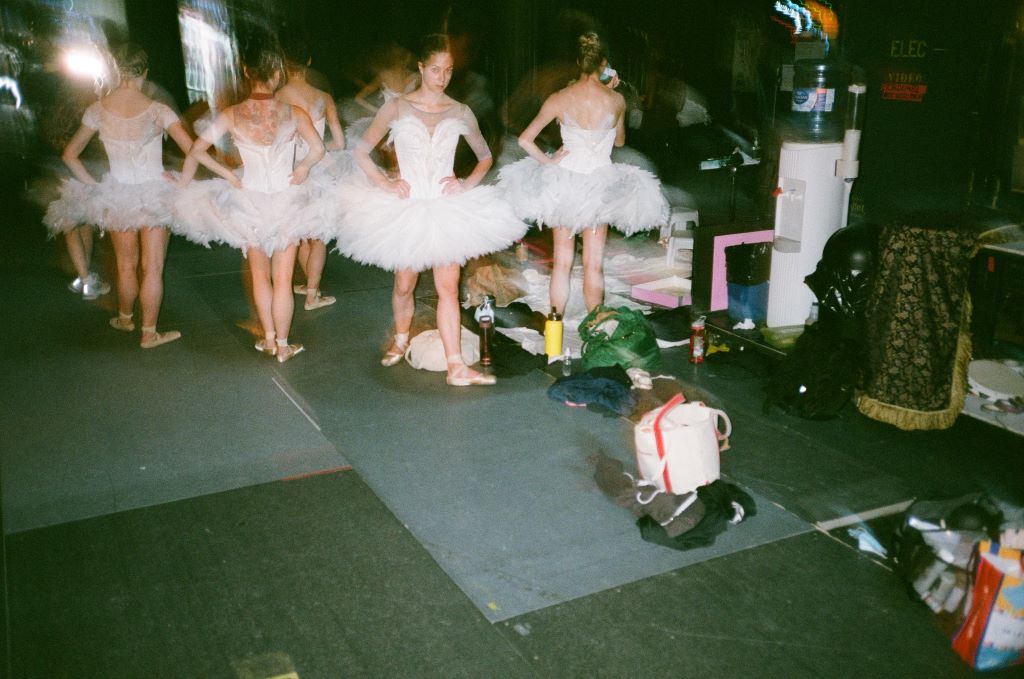

Yet when you’re watching these performers, it all seems so effortless as they float across the stage. What’s thrilling about Swan Song is that it gets up close and personal with the physical demands. Shooting on opening night, the spectacular culmination of months of work, cameras catch the dancers prancing offstage where we see them sweating profusely and heaving for breath – no longer those perfectly composed characters.

McMullan is not a dancer but a skilled basketball player, having played competitively in high school, attracting college scouts. At first, I thought this would have given them a personal window into ballet’s essential requirements: physical strength, the ability to jump and huge stamina in particular. But McMullen says basketball was more useful in their on-the-job-process of having to pivot while filming, especially during the live performance shoot when they were ensconced in a space where they could look at the five monitors showing how the many cinematographers were following the performers.

“We were using a walkie talkie system so I was calling it live,” McMullan recalls. “Follow that person, follow that person – get closer, back up.”

And if you take the wrong shot – a phrase that applies both to filmmaking and basketball – you’ve missed your chance.

McMullan and O’Neill had already done a lovely dance doc entitled Crystal Pite: Angels Atlas, which helped them prepare for a film about ballet, but they had never undertaken anything as huge as Swan Song. McMullan admits that they were constantly overwhelmed by the demands of the project, but they saw it coming. “I knew it was going to be overwhelming, so we did everything we could to prepare and find the story within. Sometimes I felt that I was drowning, doing something so big. It’s the largest production in the history of the company and what we were doing was so big for us.”

And it took time to gain the dancers’ trust. The pressures during the rehearsal phase were immense and multiplied during the live performance. Under those circumstances, a camera in your face can pull a dancer’s focus away from the task, leading to missteps, or worse, serious injury. Getting everyone comfortable, doing some give and take, listening to the dancers were all key parts of the process.

“It was really the everyday of it that helped. Don’t get me wrong, we still got yelled at a lot, but by the time we had to shoot, we knew spatially where we were allowed to be,” says McMullan. “We had many conversations with stage manages and the dancers. And serious conversations with [prima ballerina] Jurgita [Dronina]. We knew in the moment it’s do or die for them. But it’s do or die for us, too.

“The communication and negotiating we could do beforehand made the difference especially with the principal dancers. We did see each other every day. We felt that by the end it was a well-oiled machine and we had embedded ourselves enough so that we had become part of it.”

McMullan knew they’d have fascinating characters to follow. Dronina, who’d danced the lead role of Odette/Odile all over the world, does have her issues with some of Kain’s choices and has injuries she hasn’t fully shared. Choreographer Robert Binet always exudes charm even when the production looks like it might get away from him. And Kain was an obvious player to follow.

But McMullan also realized that there was something different about Swan Lake’s corps de ballet, the group of dancers that fleshes out the ensemble. Thanks to Kain’s vision, they had their own story. They weren’t just a faceless chorus line created to dance so the principals could get a rest, or a bunch of flowers making pretty pictures on the stage. Kain gave the tale a feminist twist by making the swans prisoners of the villain Rothbart, so they played a central role. The corps was the core.

So the filmmakers had to find a member of the corps as a focus. But it wasn’t easy. “I interviewed every dancer except for Shaelynn Estrada because she was injured, desperate to find out who’s that one who’s gonna help us see this world,” recalls McMullan. “When Shae returned to rehearsals, as soon as I met her, I called Sean and said, ‘We’ve found her.’ There’s no film without her because she’s our access point.”

And she’s a compelling one—candid, prone to profanity, and a perfect representation of her theory that ballet isn’t the pursuit of the art of delicacy, but, with all its dangers, profoundly punk. It’s rare for a dancer to speak so openly about how she’s feeling, says McMullan.

“They were brought up since they were six years old not to show pain or emotion or not complain, so it was really challenging. In the beginning Sean and I were freaking out. ‘What are we gonna do? Nothing’s happening. We weren’t in the right place in the right time to catch the big moments. Things are more subtle. There’s not going to be a big confrontation in the centre of the room, it’s going be on the side.

“We tried to put ourselves in the best position possible to capture those moments but documentary budgets are low and you sacrifice shooting days and time, and time is what gets you the dramatic moments. It was really hard to convince the ballet to give us that kind of access.”

As for Kain, she too is not exactly a welter of emotion. That’s surprising for someone you’d think would show outward signs of stress, directing for the first time, and someone who has a strong vision of what she wants, which sometimes conflicts with convention. The swans’ relationship to Rothbart is part of that as is her insistence that the swans not wear tights so as to highlight the diversity of the corps. It’s true that there’s zero diversity in the dancers’ body types – they’re all impossibly willowy – but, even as some members complained, for the dancers’ of colour, the decision was radical: they could present as who they are.

But where’s the panic and the passion? There is a ton of tension in the film for the viewer as opening night approaches and the production seems to faltering. But there are no heavy-duty power trips, tantrums or drama.

McMullan isn’t at all surprised by Kain’s equanimity,

“She’s not so expressive because she’s trained as a ballerina,” McMullan reminds me, adding pointedly, “but what others would convey by screaming, Karen says with just a look.”

Swan Song is now playing in limited release. A four-part episodic version is also on CBC Gem.

The winner for the Rogers Best Canadian Documentary will be revealed on March 4.