Movie reviews include A Private Life, Honey Bunch, and H Is for Hawk.

Guillermo del Toro on Frankenstein and a Life of Making Monsters

January 4, 2026

By Jason Gorber

There are few filmmakers more erudite than the three-time Oscar winning writer/director Guillermo del Toro (The Shape of Water, Pinocchio). From his screening series of classic films at TIFF Lightbox to post-screening Q&As that can easily be superior to the film they follow, his passion for cinema and his seemingly inexhaustible ability to mine the worlds of art, literature, and filmmaking make for an energizing if humbling experience.

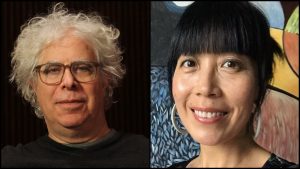

At the 2025 Marrakech International Film Festival, del Toro was awarded a career tribute trophy for his artistic contributions, but in-conversation event with the self-described “very weird guy” was a highlight of the festival. Following a conversation with his creative partner and wife Kim Morgan that saw a lineup of hundreds of locals hungry for tales from the man, a select group of international journalists participated in a conversation at the iconic Mamounia hotel.

The conversation ranged from his most recent film, Frankenstein, to his life-long fascination with the monstrous in its many forms. The filmmaker also discussed his next announced project, a stop-motion animated film The Buried Giant based on Kazuo Ishiguro’s celebrated novel. To sit in the same Moroccan milieu where Hitchcock shot The Man Who Knew Too Much prompted an obvious question about his own legacy, while the conversation also extended to films and fables that shaped him from childhood. The electric sensation with which del Toro lucidly expresses himself provided a highlight to my visit to North Africa.

Most young people are scared of monsters, yet when you were reading Frankenstein as a child, you were intrigued rather than afraid. In your films, your monsters tend to be very lovable and tender.

I was born in 1964. By then, with Japanese Kaiju movies, the monsters were all adorable. Godzilla started as a force of nature, fuelled by the power of the atomic bomb. But by the ’60s, Godzilla is already very domesticated, and he’s become the good guy.

When I read Frankenstein in the 1970s, there was a whole new culture around these creatures, having been readopted by new generations as almost heroes. By the time I came around, monsters were a lot more desirable and beautiful.

It should be noted that in her book, Mary Shelley takes exception on occasion for the monster to be considered utterly demonic. When the monster strangles little William, who is five years old, and the creature admits that he “loved it,” that is really a rare moment in the book. Mostly, what the story brings is more similar to the monologue of Caliban in The Tempest, him decrying “Why did you make me like this? Why did you give me the world and not the understanding of it?” There’s a lot of pleading from the monster with his creator. It’s equivalent to man interrogating God and saying, “Why did you throw me here?” And that’s what was very moving to me.

I was a Catholic boy, I was very, very Catholic. I would lapse. I’m now very lapsed! [Laughs.] But the cosmology of the faith intrigued me a lot. Of course, Mary Shelley entwines elements of Paradise Lost into to her novel, so there’s plenty of philosophical depth in the book.

You are currently living in the U.S. where both rhetoric and action on immigration, particularly from Latin America, is taking on darker and darker manifestations. How is the current mode of American politics affecting you personally and artistically?

We are living in a moment of atrocious politics, but also an atrocious perception of immigration. The idea of dividing people by blaming the other has been successful through the decades. For some instinctive, demonic reason, people prefer to blame those next to them rather than the people above them. We are in a particularly dire moment in that can be countered via political and legal means, of course, but also via the arts. The arts can offer the possibility for understanding that there is a second narrative. One of the things Shelley does in her book, and something the movie tries to say, is that you have heard my creator’s tale, and now I will tell you mine. That alone offers the possibility of understanding that there is always the other side to be listened to and to be empathized with. At a political level, at a social level, the possibility of recognizing ourselves in another becomes harder and harder the more things get polarized, the result of which is absolutely inhuman.

Finally getting to make Frankenstein must feel like a culmination of something, given how often it echoes in the much of your work. Does that make the next chapters of your filmmaking that much more appealing, or more frightening?

I was with David Cronenberg when he turned 74. We were having dinner and he said to me, “You have to scare yourself into being young.” And this was more or less when he was trying A History of Violence, or Eastern Promises, that were seen at the time as a departure. Years later, we can see how they are part of his vocabulary. But at the time he shot them very differently. For example, the violent scene in the Turkish bath in Eastern Promises wasn’t storyboarded. He improvised it on set, and he didn’t have a fight choreographer. He told me that he used to plan all his movies meticulously, and now he likes sometimes to shoot from the hip. So, it’s as if he’s become a younger filmmaker in his older age. That’s a very appealing thought. To be scared is very appealing to any artist, or at least that’s how it should be.

You often mention the Japanese practice of Kintsugi, where the cracks of a repair on a broken piece of pottery are left exposed as an indication of the trauma prior to the reconstruction. Even the creature in Frankenstein has similar scars or seams in its construction. When were you drawn to the notion of celebrating cracks and imperfections to make beautiful art?

Around the early 2000s, just after Pan’s Labyrinth, I was reading about Wabi-sabi, and was talking to George Lucas about it. I tried to apply that aesthetic starting with Pacific Rim. I would often be asked why I put autopsies in my movies. I responded by saying it’s about showing that something that’s dead was once alive, and by seeing the internal organs, [audiences] think “Oh, these are real creatures.” Somebody pointed out that that’s very in keeping with Wabi-sabi, the notion that if something is decaying, it was once alive. Of course, part of Wabi-sabi is Kintsugi. For me, storytelling is Kintsugi. We are broken as children, and then we repair ourselves with stories. Narrative is the golden lacquer that holds us together. I find the idea really compelling and I find the beauty in it. And, yes, the monster is designed very much like a Kintsugi object.

How is work on The Buried Giant going?

It’s going very well. I wrote the opening pages for Kazuo Ishiguro to see. We’ve had many meetings. He is a screenwriter, and I need to talk about how to adapt a book like his, which is very beautiful, but very precise, particularly regarding the dialogue. It is really incredible, but the dialogue is very stylized in that book. So, I’m trying to make sure it is not simply a kid’s movie, but a movie using the form of stop-motion, which is different.

You came up with a generation of Mexican filmmakers – Alfonso Cuarón, Alejandro González Iñárritu, and Emmanuel Lubezki – who have all had incredible success on the international stage. Are you still tight with your amigos?

I talk to Alfonso and Alejandro more than I talk to my family. We talk every week for sure, but sometimes we talk every day. That results from coming up in the same generation. I don’t talk to Lubezki that much, but Alfonso does and Alejandro does.

I come from Guadalajara, which is like coming from the Second City. Coming up from there, I bonded very well with them, because we were very undomesticated. We were very rebellious as young filmmakers, and we wanted to do something that the generation before us had not done, especially on a technical basis. We tried to push for better sound mixes, better cinematography, better construction of images, etc. We were very interested in the creation of images. Lubezki, for example, was originally going to be a director, and landed in cinematography. Alfonso, who was an assistant director, ended up directing. I was doing optical effects, makeup effects, storyboards, and so on. We all were getting good at one branch of the technical aspect of it.

We landed in a very different way because we were able to tackle genre. We were able to tackle a fairy tale or a horror movie or a drama, etc. Michel Franco, on the other hand, is from one generation later. I was very happy to see him come through, and now we support each other. At the end of the golden era of Mexican cinema, a lot of the older generation closed the ranks of the unions and said “no more new membership” in order to protect the work of the people already on the lists. We acted in the opposite fashion. We opened up the unions. In turn, we became naturally gregarious.

Alfonso, Emmanuel, and I help each other all the time. I’ve been in their editing rooms, and they’ve been in my editing rooms, I read their screenplays; they read my screenplays. We’re very close. Now, success looks better from the outside than on the inside. Success means being unemployed for three, four, five years, and nobody noticing! I’ve seen Alfonso gamble in really big ways. We’ve seen each other go through the wringer, both critically and economically, over the last years. Outside, people they think it’s a bump on the road, but for you, as an artist, it’s immediate and crushing. You think you’re never going to recuperate from that. I saw Alfonso fight vehemently for Gravity, which turned out to be a huge success. The studio didn’t believe in the movie. And yet when it’s successful, suddenly everybody always believed in it. On the outside it looks almost easy, but it isn’t.

Where does the richness of your own aesthetic derive from?

Honestly, it comes from paintings, illustrations – basically every illustrated art. For inspiration, Rousseau, Monet, in the fine arts. Or you can talk about Will Elder or Harvey Kurtzman from Mad magazine. I come from seeing visual arts as both composition and storytelling. You can have an illustrator as elegant as Kay Nielsen tackle the same thing as an illustrator as dense as Arthur Rackham.

There are sentiments from two filmmakers that greatly influenced me. One is by Hitchcock. Hitchcock said, “I went through every stage of British film that ever was. I started on silent, and when sound came to me, I didn’t take it casually. I said sound is important. And then when colour came to me, I thought, ‘Hmmm, colour is important.’ Therefore, I applied it judiciously.” Fellini said basically the same thing. He said, “When I went from my neo-realist period to my colour period, I said, ‘I’m going to use colour as expressively as I can.’” And then you have Roma, Amarcord. There’s Casanova, which is deranged-ly beautiful. He then said “Well, there’s already colour, there’s already sound, I’m going to use them judiciously to be very un-judicious. I like very much to use those things to be expressive.” In order to be truly expressive, there has to be a sense of composition. Whether you are Debussy or Wagner, you’re purposely aiming for composition.

I discussed this when I talk about people as Baroque or abundant as Terry Gilliam, Baz Luhrmann, or the Safdies. Take something like Uncut Gems: There’s a rhythm. It’s not simply starting at the top of intensity and staying there. There is a sense of composition.

You mentioned Hitchcock, and of course we’re sitting at the location of one of his films, The Man Who Knew Too Much. What does that mean to you, personally, to be here at this stage of your career, following this legend’s footsteps?

The two filmmakers I know most intimately are Alfred Hitchcock and Luis Buñuel. I have dedicated myself to studying their biographies and their filmographies. It’s fascinating to me that Hitchcock earned a lot of animosity during his British period, namely from [distributor] C.M. Wolf who was in charge of making sure movies were seen or not. [Hitchcock] struggled, and then decided his solution was to go to America. He was perceived as a very “American” British filmmaker, when in reality, he was a very German British filmmaker. He goes to America and he lands in the hands of David O. Selznick, who is a control monster. Selznick gets an exclusive, rents him out on brutal terms, and finally, when the contract is over, Hitchcock gets liberated and starts his period of being a truly American filmmaker with Shadow of a Doubt. It’s here he basically relearns all of the lessons that he learned in his British period. And The Man Who Knew Too Much, with Jimmy Stewart and Doris Day from 1956, is the moment where he rephrases The Man Who Knew Too Much with Peter Lorrie in 1934, right?

This is a very important moment in which Hitchcock decides to become a recognizable style. And then he becomes a brand. Within those periods, he becomes an auteur, or he is recognized as such. Because before, he was what the folks at Cahiers du cinéma used to call a “sequence filmmaker”: an OK director with one or two sequences in every movie where he is ingenious. The Man Who Knew Too Much lands in that moment right in the middle of becoming to be truly valued. Eventually, he does what only three filmmakers or four filmmakers have achieved. He’s not only a name above the title: He becomes a brand. For my films, I think I am an acquired taste. [Laughs.]

Yet it’s Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio. It’s Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein.

With Pinocchio it was necessary because it was about the rise of Mussolini and I didn’t want families to go, “Let’s go see Pinocchio,” [and then say] “Oh my God, what the fuck is this?” But I think Hitchcock is a really interesting case. I think once Cahiers du cinéma finally articulated all of that after the mid-1960s, he got slightly confused. He found his footing with Frenzy, but never again.

Both Pinocchio and Frankenstein are stories about men who build something new and create life in an unnatural way. In a way, filmmaking echoes those acts of creation. Do you share any of the anxieties reflected by the creators in those films?

Mary Shelley feared birth. She feared the feminine mortality that came with birth. She miscarried a number of times before writing the novel, and her mother died giving birth to her. So that is ingrained in the text. This is not something that you approach thematically. The same thing happened to me as a kid. My mom almost died and she had miscarriages, and her mother died in childbirth. That was ingrained in my id. So the unnatural birth without the feminine agency is very Mary Shelley. The fact that the father is absent also as a figure is really very telling.

I grew up in a world without mothers in fiction. In every Walt Disney comic book, they were nephews. Donald Duck was not married to anyone, but had three nephews. Mickey Mouse had a nephew. There were not married couples in the imagination of Disney. Every fairy tale had a step-mother or a step-father. I grew up in a mythology where the family nucleus was always broken, as in Pinocchio and in Frankenstein. I mean, there is a Freudian school of analysis that says that it is not an accident that Victor lies spent in bed and his creation looks at him back from the foot of the bed. Freud can do with that what you may, but there is a school of analysis that says it’s a “Lonely pleasure.” I leave it to you guys to accept or reject.

You’ve also had many cinematic stillbirths. There’s a certain one involving Peter Jackson [The Hobbit], but there are many others that never survived. You talk about the children that didn’t make it, so do these unborn projects still hold a place in your heart?

They do. But you don’t watch the home movies of your ex-wife with her new husband. It’s bad if they’re bad, and it’s worse if they’re good.

Will you ever make a movie as big as Frankenstein again?

I don’t know. It’s all about whether the appetite for difficulties matches the appetite for achievement.