Reviews include Irena’s Vow, The Beast, and Before I Change My Mind.

TIFF 2021 Festival Report: A Virtual Event in Four Acts

September 19, 2021

By Rose Ho

I’ve never attended a film festival like this one before. Sure, I’ve watched a few films in previous iterations of the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF). They were usually small, international flicks or awards-buzzy Hollywood fare. I even did some in-theatre volunteering in 2014, but I’ve never had the level of access that media accreditation offered nor the convenience of attending a festival virtually under TIFF’s banner that I did this year. It’s been exciting flipping through the film program with a selection of over 100 movies, trying to watch as many titles as I can handle on top of a nine-to-five workweek plus extracurricular activities.

Of course, there are still plenty of things I missed out on because not everything was available online. Some of the hottest films of the festival circuit — Dune, Last Night in Soho, Spencer — were only available on the big screen, and, unfortunately, remote viewing was all I could do. I also missed the interactions with other film lovers that happen at in-person screenings and industry events. Those are critical elements of the festival experience that cannot be overlooked or replaced in a digital format. Sitting alone in my room, streaming the TIFF Tribute Awards Press Conference, and reading a handful of fun comments in the sidebar is really not the same as attending in person.

However, I did have unfettered access to some really interesting films. I tend to gravitate towards period pieces and international dramas, so my selection may seem scattered. If there is a through-line, however, that I discovered while watching these movies, it may be one of loneliness, loss, and connection. These themes have particular poignancy in a pandemic.

The first film I watched was Mothering Sunday — a dreamlike tale of a writer, the orphaned maid Jane Fairchild (Odessa Young), who reflects on the final afternoon in the summer of 1924 that she spent with her lover, Paul Sheringham (Josh O’Connor), a wealthy young man about to marry someone else. Hanging over the events of that sultry day in the English countryside is the weight of unspeakable grief among the Sheringhams and their neighbours (and Jane’s employers), the Nivens (Colin Firth and Olivia Colman). The close-knit families had lost their sons during the war and subsequently pinned their happiness on gentle and dutiful Paul, the only survivor. O’Connor, best known for portraying Prince Charles on Netflix’s The Crown, is outstanding, as well as newcomer Young. This beautifully lensed film is an adaptation of Graham Swift’s 2016 novel and, as director Eva Husson explained in her introduction to the film, Mothering Sunday is about personal and collective loss, which seems apt for our current time.

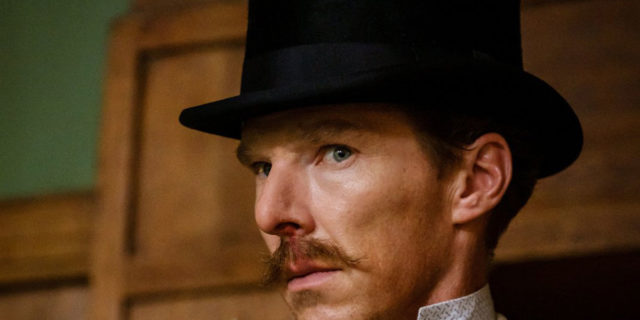

Another literary adaptation with a female director is TIFF’s revisionist western The Power of the Dog, directed by Jane Campion and based on the book by Thomas Savage. Benedict Cumberbatch presents a tour de force performance as Phil Burbank — a seething, controlling, and experienced rancher who antagonizes Rose (Kirsten Dunst), the new wife to his brother George (Jesse Plemons), and her son Peter (Kodi Smit-McPhee) when they move to the Burbanks’ remote property. Simmering with one kind of tension before switching to another, The Power of the Dog evokes tales of Gothic horror in which domestic violence threatens to erupt. However, Campion’s slow-burning film ultimately takes an unexpected turn to inspire another kind of release.

Campion displays the isolation of her characters in physical and emotional space beautifully. She harnesses the power of the vast, dusty vistas of New Zealand (presented as 1920s Montana) and the shadowy interiors of the Burbank mansion. In one understatedly moving scene, one character breaks down in happy tears to say that he finally feels like he not alone, despite the film having showed him living on an apparently busy ranch and having all the trappings of success. Cinematographer Ari Wegner was honoured with this year’s TIFF Variety Artisan Award for her stunning work in this film and in others like True History of the Kelly Gang and Lady Macbeth.

Cumberbatch starred in another TIFF selection, playing the title role in the quirky biopic The Electrical Life of Louis Wain. Wain is an autodidactic, once-affluent eccentric and artist who achieves fame for his illustrations of anthropomorphized cats in the 19th century. Marrying his younger sisters’ forward-thinking governess Emily Richardson (Claire Foy), Wain expresses a quiet rebellion and avant-garde sensibility during the usually stuffy Victorian era that sets him apart from the rest of society — for better or worse. Director Will Sharpe portrays Wain’s eventual devolvement into mental illness as has he did in his TV show Flowers (where Olivia Colman, the narrator of Electrical Life, had a starring role), which is to say with equal parts dark humour and pathos in a distinctively frenetic style. His timeworn message of love, beauty, and human connection through art (even kitschy, populist art) is handled deftly and feels earned. With a liberal sprinkling of cameos by cult comedians like Julian Barratt, Richard Ayoade, and Jamie Demetriou, Electrical Life is an expected delight.

After a long stretch from being unable to watch a screening after work, I finally managed to switch from period pieces starring British talent to international cinema with Are You Lonesome Tonight? This gritty little neo-noir is the feature debut of Chinese director Wen Shipei. Taiwanese actor Eddie Peng plays an air conditioner repairman who accidentally runs over a man with his truck, hides the body, and is subsequently consumed by guilt. Trying to find atonement, he finds himself compulsively (or perhaps fatefully?) drawn to the victim’s widow, Mrs. Liang (Sylvia Chang), but other unsavory characters also begin circling around them. Observations of the widow’s loneliness and the complicated process of mourning are filtered through the camera and the protagonist’s eyes in a simple but deeply affecting manner. The musical cues are also strong with a beautiful rendition of the titular Elvis song sung by an intriguing side character. The visuals of Lonesome are handled assuredly with strong camerawork, editing, and deliberate use of red accents and lights in almost every frame. The pops of colour become an ominous but strikingly cohesive element in the film. They stand in contrast to the many nighttime scenes and the grimy interiors of the criminal underbelly of the city before finally exploding across the screen in the violent climax of the movie.

While I did not get to see nearly as many films as I had wished to catch in the festival’s ten jam-packed days, it was a sweet thrill to watch the ones that I did. The lonely experiences on and off screen were transmuted by the precious connections that still managed to be forged by the power of cinema, which ultimately can connect people across time and place, from a century-past Wild West to Victorian-era London and late ‘90s China.