Reviews include Irena’s Vow, The Beast, and Before I Change My Mind.

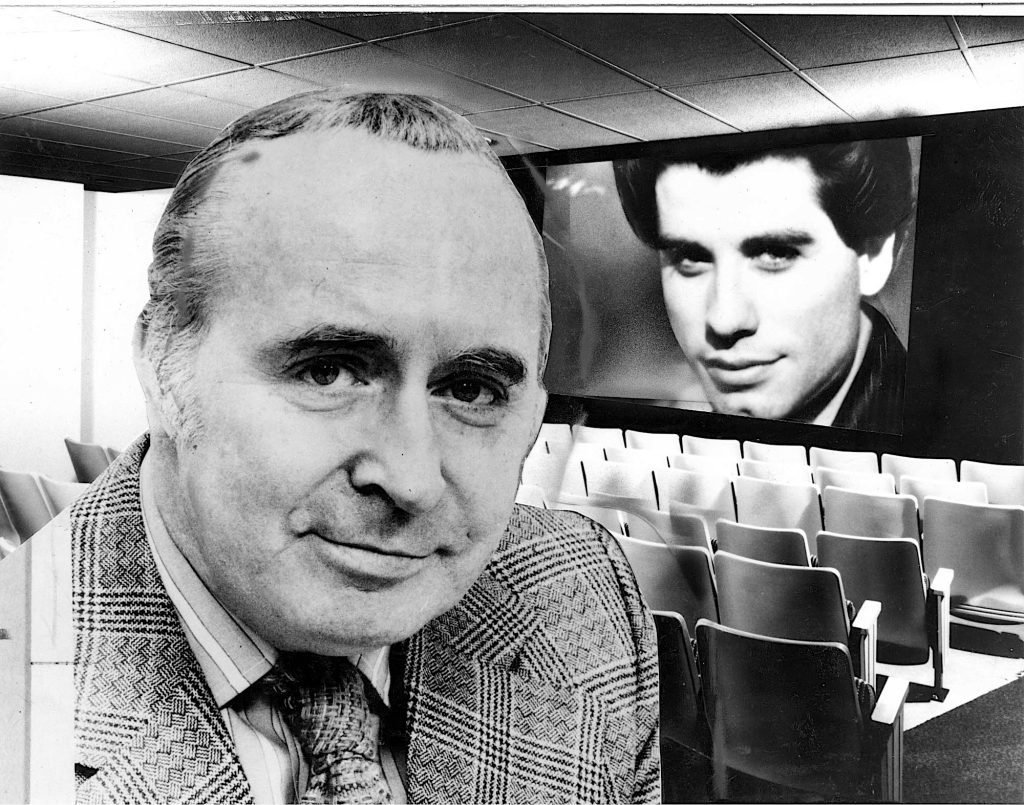

Toronto movie critic legend Clyde Gilmour wrote with authority but also a common touch

January 19, 2023

By Peter Howell

Journalists like to consider themselves unique individuals, but legendary Toronto movie critic Clyde Gilmour truly walked the walk, long before his name adorned one of the TFCA’s most cherished awards.

A fiend for punctuality, Gilmour always wore two wristwatches, just to be sure. He adored movies but thought film festivals were excessive; he made a point of taking his annual vacation during Toronto’s September film fest.

Gilmour, who died at age 85 in 1997, the year the TFCA began, didn’t like doing celebrity interviews. Yet his favourite anecdote was the time he almost had a picnic with Marilyn Monroe in 1951, when he was writing for the Vancouver Sun and Monroe was a rising Hollywood star. The picnic was scratched after Gilmour’s editor ordered him to fly to San Francisco for the return of controversial Korean War hero Gen. Douglas MacArthur. Gilmour was told to cover it “like a movie.”

During his lifetime, Gilmour was honoured with memberships in the Order of Canada and the Canadian News Hall of Fame for advancing the country’s culture, not just through his decades as a movie critic at the Toronto Star, the Toronto Telegram (aka “the Tely”), the Vancouver Sun, Maclean’s, and the CBC, but also as host of “Gilmour’s Albums,” a long-running and eclectic music program on CBC radio.

Gilmour was a national institution, a fount of film and music knowledge, yet he disliked being recognized in public. His obituary in the Star Entertainment section said that if people on the street asked him if he was the Clyde Gilmour, he was inclined to reply, “No, but people often mistake me for him.”

It’s possible, then, that he wouldn’t have been too upset to learn that the Company 3 Clyde Gilmour Award, bestowed annually by the TFCA for the past 25 years to “someone who has made a substantial and outstanding contribution to the advancement and/or history of Canadian cinema,” is getting a name change as the association refreshes its awards. The award, of which past recipients include actor Tantoo Cardinal and directors Norman Jewison, Deepa Mehta, Alanis Obomsawin, and, most recently, David Cronenberg, will now be called the “Company 3 TFCA Luminary Award.” Although the award no longer bears Gilmour’s name, the spirit that inspired it remains the same.

Gilmour’s name may not be part of the TFCA’s ongoing story but he won’t be forgotten, especially by the generations of people who read his movie reviews in the Star and Tely, and by devoted CBC listeners who tuned into his album selections for more than 40 years. He played tunes from his personal collection of more than 13,000 albums, which are now in the CBC archives.

In his heyday, Gilmour’s verdict on a film was considered gospel by many Toronto moviegoers, who first read him in the Tely from 1954 to 1971 and then, following that paper’s demise, in the Star from 1971 to 80, with occasional dispatches after that. His muscular prose left no doubt about his opinions, yet he wrote with authority and a common touch.

I remember as a kid being in such awe of Gilmour that, on the rare occasion my family went to a film on opening day, I would look around the theatre to see if I could spot him. I didn’t know then that critics see movies in advance of opening day, so they can write their reviews. I certainly learned about that perk of the job long before I became the Star‘s movie critic, a job I’ve had since 1996, ever mindful of Gilmour’s legacy.

Journalist and novelist Ron Base (Death at the Savoy), who succeeded Gilmour as the Star’s movie critic in 1980, has a similar story of a youthful obsession with the man.

“I grew up reading Clyde,” Base told me. “I was the kid in Brockville who loved the movies, but had very little access to any news or reviews of the movies back in those days. Clyde was my man on the front lines, bringing me the news of Lawrence of Arabia or From Russia with Love or Tom Jones or La Dolce Vita,’all these films that I absolutely hungered for and was obsessed with. He was there writing about them, often with a sense of humour.”

Gilmour’s favourite movies were The Maltese Falcon and Casablanca, both starring Humphrey Bogart. Although he favoured traditional three-act structures over newer forms of storytelling, he was nevertheless interested in movies from around the world and enthusiastically reviewed them.

“Toronto was on the forefront of a lot of foreign films that were opening, and he was certainly there to talk about them. My memory is that he was an admirer of most of the foreign films he was seeing,” Base said.

Gilmour was also able to appreciate a formally challenging picture like Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, a mind trip that confounded viewers and reviewers alike upon its arrival in 1968. Despite warning his readers in the Toronto Telegram that they might have trouble understanding this film of many symbols and scant dialogue, Gilmour did an interview with the press-shy Kubrick for the Tely that was so illuminating, it’s been quoted in books about 2001.

But if Gilmour had a knack for deciphering movies and winning over difficult directors, he wasn’t exactly a social butterfly. When Base took over from Gilmour in 1980, having worked as the Star’s TV critic for the preceding year, it wasn’t lost on him that he was stepping into the shoes of his idol. Gilmour, however, had no time idle chit-chat, declining Base’s request for a getting-to-know-you lunch.

“He was totally uninterested,” Base said. “This was my excitement; it sure wasn’t his. He was kind of a gnome-like guy, but a very pleasant, sweet man.”

Gilmour got along with his Star colleagues well enough. He just didn’t want to socialize with them all that much. He preferred to write people notes using comic pseudonyms; “Kosmos Kagool” was a favourite.

Clyde Gilmour may not have been the first full-time movie critic for a Toronto newspaper — Globe and Mail writer Frank Morriss was covering the beat in the 1950s and may have preceded Gilmour locally — but he was the top dog on the movie beat at least until the 1970s, when Jay Scott at the Globe and George Anthony at the upstart Toronto Sun tabloid became rivals worthy of the name.

Recalled Base: “When I first started (as Star movie critic), I remember one of the exhibitors taking me to one side and saying, ‘You know, Clyde Gilmour was a very influential critic here in Toronto. If Clyde liked the movie, you could see the box office go up. I’ve never seen that with another critic.’

“I think that was true,” Base said. “I think Clyde did have an influence on the local movie scene at that time. That has not been replicated since. I certainly didn’t have it.”

A few quick cuts from memorable Clyde Gilmour movie reviews:

The Godfather (Francis Ford Coppola, 1972):

“Marlon Brando decisively re-establishes himself as the foremost American screen actor with his remarkable portrayal of an aging Mafia chieftain in The Godfather, a flawed but powerful movie … It’s still probably the best gangster movie ever made.”

The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973):

“If you thought Rosemary’s Baby was scary, wait until you see The Exorcist. It makes Roman Polanski’s 1968 sensation seem as mild as a Disney kiddie-show … The result is a well-crafted two-hour movie that begins slowly and confusingly but finally packs a terrific wallop. And the wallop is there whether you’re a devil-worshipper yourself or totally reject mankind’s ancient belief that Satan exists and has infinitely evil powers.”

Star Wars (George Lucas, 1977):

“Lucas himself says his new film is not really science-fiction but a live-action comic strip, ‘a shoot-em-up with ray guns.’ It distills the joys he cherished as a youngster while watching movies and TV shows and soaking up the adventures of Flash Gordon. There are touches of The Wizard of Oz in it, along with the Hardy Boys and Arthurian romances and a thousand half-forgotten westerns.”