Reviews include Irena’s Vow, The Beast, and Before I Change My Mind.

Werewolves (and Witches and Elephant Men) of London: British Gothic Cinema at TIFF

October 22, 2015

by Adam Nayman

Whilst out making the junket rounds for Crimson Peak, Guillermo Del Toro has taken every opportunity to clarify that his latest elaborately art-directed effort is not simply a genre movie but a “Gothic romance”—less The Devil’s Backbone than Charlotte Bronte. Del Toro would know, as he recently conducted a series of master classes at TIFF Bell Lightbox in which he waxed rhapsodic – and Gothic – about the film versions of Jane Eyre, Rebecca, and Great Expectations, all of which are duly referenced in Crimson Peak’s tale of an innocent young American writer (Mia Wasikowska) relocated via marriage to an exquisitely dilapidated (and, yes, haunted) British mansion.

Besides being timed to help hype Crimson Peak’s release, Del Toro’s lectures served to set up the Lightbox’s most eagerly anticipated fall series on Gothic cinema, which begins this Friday (October 23rd). The selection is slender compared to the original BFI retrospective, which rolled out over 150 titles in screenings across the UK; TIFF has chosen a mere 11 titles to reflect and represent a cinematic lineage almost as old as the medium itself. But it’s a true murderer’s row of movies—a scattering of classics that doubles as a pocket history of British genre filmmaking.

The oldest film on offer is Dead of Night, an elegant anthology from 1945 co-directed by Robert Hamer, Basil Dearden, Charles Crichton and Alberto Cavalcanti – all gifted craftsmen enlisted to try their dab hands at something scary. The most enduring episode was Cavalcanti’s tale of a ventriloquist bewitched by his own wooden dummy; Michael Redgrave’s beautifully tortured performance in the lead role became ground zero for actors trying to convey creeping madness. That Dead of Night was produced by the legendary light-comedy-factory Ealing Studios is more than a historical coincidence; it illustrates a symbiotic relationship between humour and horror that would inform many more UK genre movies to come.

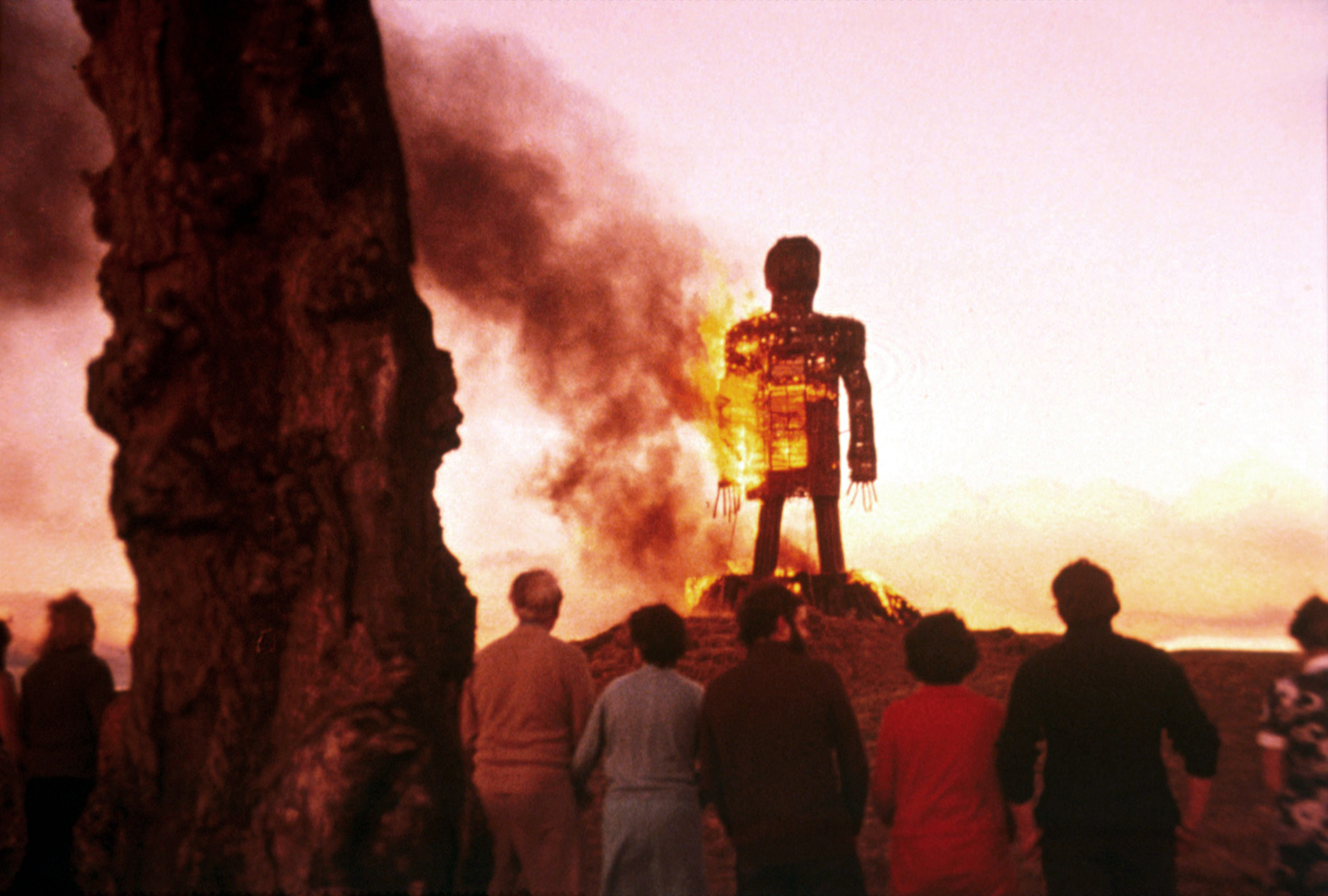

Case in point: The Wicker Man (1973), a hilariously funny fable about a London police officer (Edward Woodman) hoisted on his own pious petard by the denizens of an isolated island cult; by casting Christopher Lee—aka Count Dracula himself—as a messianic cult leader, Robin Hardy aligned his putative villains with the glories of the Hammer Studios horror movies of the 1960s. The Wicker Man’s climax is iconic and ironic in equal measures; the spectacle of a man of God falling prey to pagans carried a potent counter-cultural charge at the time.

When it was first released in theatres, The Wicker Man was often double-billed with Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now, a thriller adapted from a short story by Rebecca author Daphne Du Maurier. Where Hardy’s film is cheerfully perverse, Roeg’s classic is genuinely unsettling. It’s set in Venice, which appears here as a city sinking into the sludge—a perfect externalization of star Donald Sutherland’s grief-stricken psyche. Of all the ghostly figures in British horror cinema, none casts as long a shadow as the red-hooded cipher seen flitting about the edges of Roeg’s meticulously composed frames – an image later paid tribute in movies as diverse as Schindler’s List and Casino Royale.

The Wicker Man and Don’t Look Now have both proven extremely popular and influential (indeed, they arguably combine in the DNA of Ben Wheatley’s great Kill List [2011]) but there are some comparatively obscure films in this programme as well. For instance, there’s Michael Reeve’s defiantly un-genteel 17th Century period piece Witchfinder General (1968), with a never-better Vincent Price as a sadistic witch-hunter; like The Wicker Man, the film depicts a national-historical tension between belief systems except that here, the violence is imbued with real pain and terror. Also worth seeking out is Neil Jordan’s impressively stylized 1984 adaptation of Angela Carter’s post-modern novel The Company of Wolves, which unleashed the sexual subtext of old Grimm fairy-tales; Jordan’s red-hued vision of budding femininity beset by predators (literal and figurative) is brilliantly expressionistic.

And then there’s David Lynch’s masterful The Elephant Man (1980), which is set in London at the turn of the 20th Century and smartly locates the link between an English literary tradition of shadows and superstition and the nascent industrialization that transformed a country’s economy and topography. John Hurt’s deformed, poetic John Merrick is the bridging figure in this allegorical-historical transition, and he’s one of the great tragic outcasts in film history—a Romeo disguised as Caliban. Lynch’s decision to shoot the first thirty minutes or so like a monster movie (withholding its subject out of fear and anticipation) before switching to Merrick’s point of view—and all of the lyricism it contains—is a stroke of genius, showing both canniness and compassion. The Elephant Man accesses and assesses fears—fear of the unknown; fear of loneliness; fear of mortality—that even the scariest midnight classics can’t touch. It’s not a horror movie, but it’s positively Gothic nevertheless.