Reviews include Irena’s Vow, The Beast, and Before I Change My Mind.

Is Sex Still Subversive? Considering Red Rocket, Benedetta, Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn, and Titane

January 11, 2022

By Marc Glassman

Film has the capacity to change the critical conversation on the state of the world. It’s still the most popular art, the one that provokes vigorous debates when its intentions strike a chord with the public. In an increasingly divided world, what unites us is a fear of a continual pandemic and a love/hate relationship to the systems that govern us economically and politically. Given the climate we’re in, which includes so many dire threats, especially the trepidation on what has been done to our environment, what galvanizes us to subvert the orthodoxies we’re presently enduring?

There’s not one answer to such a query, of course, but it’s reasonable to examine one of the strategies that was employed in some of 2021’s finest films. What links Red Rocket, Benedetta, Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn, and Titane is the employment in each film of sex as the weapon of disjuncture. The filmmakers—Sean Baker, Paul Verhoeven, Radu Jude, and Julia Ducournau, respectively—are questioning the societies in which they live and forcing viewers to look at core beliefs in the systems that govern them. Rather than engaging in direct confrontation with racism, environmental indifference, or corporate pathology, these films offer narratives where sex is at the forefront of the tale and any analysis must be drawn from thinking through the story itself.

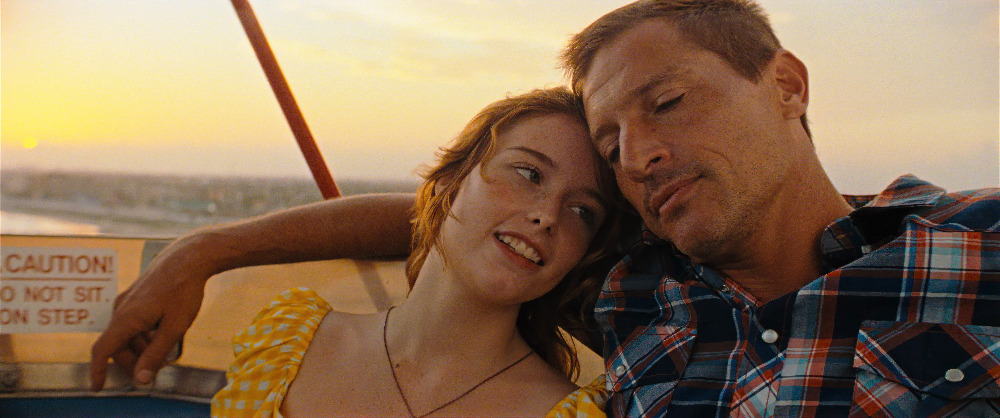

Red Rocket may be the most subversive of the quartet since it never engages in a critique of the locale or the characters it depicts. Like Sean Baker’s previous films, Tangerine (2013) and The Florida Project (2017), it plunges us into the unexamined lives of people existing on the margins of America. He cast Simon Rex, who worked briefly in the sex film industry before going on to star in lowbrow Hollywood films, as Mikey Saber, a former porn star, down on his luck, returning to his hometown of Texas City on the Gulf Coast. Mikey’s abortive attempt at starting over with Lexi (Bree Elrod), his ex-wife and former porn partner, is almost immediately derailed by his inability to get a job, which leads him to start dealing pot. Working with his old dealer, Leondria (Judy Hill), Mikey becomes so successful in dealing that he’s able to hook up with a 17-year-old donut shop waitress, Strawberry (Suzanna Son)Mikey eventually convinces Strawberry that they should go to L.A., where he can turn her into a new porn star. This inverse Pilgrim’s Progress might have worked out for Mikey if he didn’t make the mistake of letting Lexi know he was leaving: her revenge deprives him of the cash to make a get away with Strawberry.

Baker places Mikey’s hometown journey during the summer of 2016, when Donald Trump launched his campaign to get the Republican nomination and the Presidency. No one comments on Trump, but he’s seen on TV, providing a context for what’s happening to Texas City and its denizens. Mikey is so amoral and guilelessly ambitious that Baker invites viewers to root for him even when he leads his luckless next-door neighbour into driving so badly that he causes a huge traffic pileup causing death and destruction. The only thing Mikey is good at is sex. Lexi and Strawberry are more than satisfied with him—in the bedroom, anyway. Both Mikey and Trump love sex and manipulating people, particularly women, into helping them to become richer and more powerful. Mikey’s schemes fizzle out in Red Rocket, culminating with a run from his problems wearing only his birthday suit, but Baker leaves us with the disquieting realization that he’s learned nothing from his failure—and that’s equally true of the society from which he’s emerged.

Paul Verhoeven, similarly, is a master at depicting the disruptive elements of sex—his credits include Showgirls (1995), Basic Instinct (1992), and Elle (2016)—so it’s no surprise that Benedetta trades in that territory. Unlike the other films, Benedetta is set in the past, in 17th century Italy. It recounts the astonishing story of Sister Benedetta Carlini, who had visions in which she married Jesus and actually appears to have developed stigmata at one point in her twenties. Her life is unusually well recorded for the time because she was subjected to two ecclesiastical trials, which exposed that she had lesbian relations with another nun, Sister Bartolomea. Verhoeven based the film on a scholarly work by historian Judith C. Brown entitled Immodest Acts: The Life of a Lesbian Nun in Renaissance Italy. Besides being a filmmaker, Verhoeven is a member of the Jesus Seminar, a group of biblical scholars and laypeople. They engage in discussions on the historicity of Jesus and Verhoeven is the co-author of a book on the subject, Jesus of Nazareth.

It’s necessary to validate the scholarship that informs Benedetta since Verhoeven relishes the absurdity of Benedetta’s situation and knowingly plays up the eroticism of the material. The Dutch auteur is a provocateur who deliberately subverts conventional approaches to genre and narrative. RoboCop (1987) and Starship Troopers (1997) push violence to such extremes that they seem laughable—and yet, the narrative compels the viewer to cheer on the resultant destruction. Basic Instinct took its femme fatale thriller plot and blew it up, creating a more violent and far sexier genre. With Showgirls, he apparently went too far in equating overarching ambition and blatant sexuality in America’s ultimate vulgar paradise, Las Vegas. Since that time and despite the overwhelming success of Black Book (2006), many critics and some members of the public refuse to take Verhoeven seriously.

That’s where the pleasure in Benedetta lies: it’s so blatantly and overtly salacious that you know Verhoeven was having a fine time shooting it. (Highlights include orgasmic stigmatic, a Jesus with unusually heightened sex appeal, and penetration with a crucifix.) And yet, what he’s doing is taking apart the ideology of that time, and truly for centuries: male dominated Catholicism, offering instead a wonderfully divisive figure, a nun who may have married Jesus and suffered his stigmata, but was also a lesbian and perhaps a heretic. The fact that the historic Benedetta and the film version survive inquisitions—though in different ways—and live to a ripe old age must be immensely enjoyable to Verhoeven. In any case, risible or satirical, the very sexy Benedetta surely takes apart its time and place.

In Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn, which won the Golden Bear at Berlin, Rumanian filmmaker Radu Jude uses a filmed sex scene to interrogate his hypocritical culture. The opening sequence comes closest in any of the films to showing real hard-core sex on the screen. We see what looks to be an amateur shoot of a couple having sex while role playing and indulging in a bit of S&M. The rest of the film is presented in three chapters, arising from the shooting and distribution of the home-movie. In the first chapter, Emi (Katia Pascariu), a high school literature teacher, visits the institution’s headmistress, who lets her know that the tape she and her husband made has gone viral. Parents have seen it and have demanded an open meeting that night to force her dismissal.

A very disturbed Emi wanders the streets of Bucharest, weaving in and out of pedestrian traffic, going into shops, avoiding cars, and occasionally talking to her husband on the phone. It is lucid, clear-eyed street documentary: we see worn-out city dwellers barking at each other—harassing and being harassed. Emi has problems but so do all of them. In the second chapter, called “definitions,” narrative is abandoned completely. Voice-overs, archival footage, and graphics predominate as Rumania’s past dirty secrets are revealed: complicity with the Nazis until it made sense to switch sides to the Communists, the human rights abuses and sheer corruption of the Ceausescu regime, the history of anti-Semitism and anti-Roma persecutions, etc.

In the third chapter, the confrontation between Emi and the schoolchildren’s parents is shown in all its painful absurdity, including when the men present insist on reviewing the tape together. The accusers are clichéd representatives of the hypocritical Church, the military, and the most obvious forms of conventional morality. Emi fights back with candor and brilliance, citing figures as disparate as Hannah Arendt and a Rumanian poet laureate, to make her case against her COVID-masked attackers. Jude’s film uses a sex tape to challenge the Rumanian orthodoxy: he emerges, with Emi, as the flawed, all too human exemplar of intellectual freedom.

Julia Ducournau’s Palme d’Or winner Titane is a fever dream of a film. It exists as a nightmare vision of contemporary France, a place of disjointed sex, glamour, and violence. Alexia (Agathe Rouselle), a gorgeous on-the-edge sports car model with titanium surgically inserted in her head, is given to murderous rages and over-the-top sexual acts. The most outrageous of these is being impregnated by a particularly randy automobile. On the run from the police, she decides to transform her appearance into what a man, who disappeared as a teenage boy a decade ago, might look like today. By breaking her nose and binding her body with tape, she somehow convinces the still distraught father of the missing child (Vincent Lindon) that she is he. The loving relationship that these two completely mismatched people develop for each other propels the film towards a concluding birthing scene that matches the best in Cronenberg’s oeuvre.

Titane uses sex and violence to reflect in a blistering, take-no-prisoners manner, on what is happening in Western society today. Is everything either folly or sensationalism? The film suggests that there’s nothing more to believe in, not even sex or gender. And, as Dylan once put it, when you’ve got nothing, there’s nothing to lose.

Four films. Four dark visions of the world we inhabit. Using sex as a driver, these films challenge orthodoxies that are falling apart in front of our eyes as conditions in the world worsen. While this quartet of festival award-winners from 2020 will never be popular successes, they do paint a picture of where we’re at today. Can the use of sex in cinema still be subversive? These films show that the personal may be more political than ever in contemporary times.

Want to see these films?

Red Rocket is in select cinemas from Mongrel Media, Benedetta is in select theatres and in digital release from IFC Films, Titane is in digital release from Elevation Pictures, and Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn opens in digital release at TIFF Lightbox on Jan. 18.

Marc Glassman is the editor of POV Magazine and contributes film reviews to Classical FM. He is an adjunct professor at Ryerson University and is the treasure of the Toronto Film Critics Association.